Traveling Trajectories and Sequences with Poet Shin Yu Pai

Shin Yu Pai is the author of several poetry books, including AUX ARCS (La Alameda, 2013), Adamantine (White Pine, 2010), Sightings (1913 Press, 2007), and Equivalence (La Alameda, 2003). She has also published a number of limited edition artist’s books, including Hybrid Land (Filter Press, 2010), Works on Paper (Convivio Bookworks, 2007), and The Love Hotel Poems (Press Lorentz, 2006).

A visual artist, she has exhibited her work at the Paterson Museum, The McKinney Avenue Contemporary, and the Three Arts Club of Chicago. She is a former curator for The Wittliff Collections and has taught creative writing at Southern Methodist University and the University of Texas at Dallas. Pai received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and studied at Naropa University.

A recipient of awards from the Arkansas Arts Council, 4Culture, the City of Seattle’s Office of Arts & Cultural Affairs, and the Cambridge Arts Council, Pai has completed residencies at the Ragdale Foundation, Taipei Artist Village, Soul Mountain, and is a three-time fellow of The MacDowell Colony. Over the years, P&W has supported numerous events she has taken part in as a writer in the Seattle, Washington area. What are your reading dos and don’ts?

What are your reading dos and don’ts?

There are few things worse than not being able to hear the reader you’ve travelled distances to hear, so I almost always use the microphone if one is given, and I test it with the audience before proceeding with a reading. I also share information with an audience on the contexts of my poems to engage them in the process that informed the writing, so that my poems can be more accessible. I adhere to the time given to me and respect the time of my co-readers and audiences, and am conscious of listener fatigue. The don’ts are implicit in the dos.

How do you prepare for a reading?

When I started giving poetry readings fifteen years ago, I would practice reading my poems out loud and time the material, writing out comments in the margins of my work of information I thought might be helpful for an audience. Over time, as I’ve matured as a writer and grown more into who I am as a person (an unapologetic introvert with a penchant for occasional extroversion when it comes to poetry), this approach felt too polished or rehearsed, and less spontaneous.

While I never just wing an event with zero preparation, I do now often leave preparing for an event until the day of a reading to see what feels true to me in a given moment. I try to be who I am in front of an audience so that the poems can speak from my heart. I aspire to show up, instead of acting out a public persona.

I also give thought to the venue for which I will be reading. When I read recently at a P&W–supported event with The Wing Luke Museum in Seattle, I thought about the audience for the museum, which has a focus on Asian-American history and identity. I shared poems from my most recent book Aux Arcs on race and my experiences as an Asian-American woman living and working in the South. As a museum studies graduate student, I had spent time at The Wing cataloguing collections, including loaned items from the artist Roger Shimomura. So I also shared a poem that I had written inspired by contemplating Shimomura’s pop culture self-portrait of himself as “Washington Crossing the Delaware.”

Have the disciplines of photography and art curating crossed over into your writing, and the way you think about poetry and presentation?

Poetic presentation is not simply about an experience of activating randomly selected poems by reading them aloud to an audience. I think in terms of trajectories and sequences—images that talk to and across one another for specific audiences based on themes that can arc across different bodies of work from the present and past. I think in terms of editing/curating for presentation and making spaces for the listener to enter the stream of consciousness.

I have often been asked to give slide show presentations in which I talk about the influence of visual artists on my work in tandem with reading my poems. I do think that these sort of hybrid presentations can be a useful way to engage an audience in one’s creative and analytical process.

Presentations are really a kind of event or happening—for the book launch of Aux Arcs, I invited artist Whiting Tennis, who provided the cover art for my book, to perform his folk rock music at the event. Since the poems reflect on race and the experience of living in the South, I asked Whiting if he would perform some of his more lyrical folk songs, in particular a ballad about John Brown to create a bridge to the poems.

What do you consider to be the value of literary programs for your community?

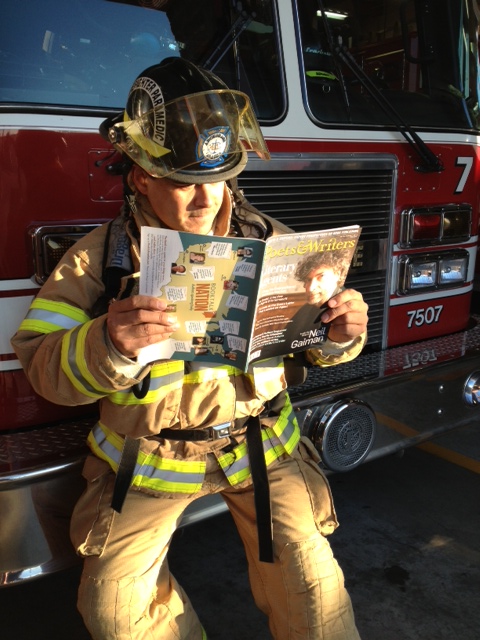

You never know when something you read or say in a workshop will light a fire for someone and inspire them to explore their own story or creative expression. The value of literary programs is in providing a model for the community that individuals of all ages, experiences, and educational backgrounds might explore the richness, inherent worth, and complexity of their own vision—that audience members may see something of their own experience mirrored in my poems, and take that experience and run with it. Poetry is for the community and acts as tool to build community. When I say community, I don’t mean the literary audience of poets and writers, academics and peers. I mean everyday people engaged with the struggle and art of living fully from an authentic place that brings together mind, spirit, and heart.

Photo: Shin Yu Pai. Credit: Daniel Carrillo.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Seattle is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Founded by Dzanc in 2011 and inspired by Lisbon poet Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the annual DISQUIET International Literary Program is a two-week retreat that brings together North American and Portuguese writers in the heart of Lisbon. The program offers

Founded by Dzanc in 2011 and inspired by Lisbon poet Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the annual DISQUIET International Literary Program is a two-week retreat that brings together North American and Portuguese writers in the heart of Lisbon. The program offers

Poets may submit up to three poems of any length; prose writers may submit a short story or essay of up to 8,000 words. The entry fee is $20, which includes a copy of the Spring issue. Submissions will be accepted online via

Poets may submit up to three poems of any length; prose writers may submit a short story or essay of up to 8,000 words. The entry fee is $20, which includes a copy of the Spring issue. Submissions will be accepted online via  I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.

I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.

Can you tell us about your organization WordPlay?

Can you tell us about your organization WordPlay? c/o Poetry Editorial Board, Sonora Review, English Deptartment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85719. A cover letter with a brief biography and contact information should be included with submissions, but names should be removed from all manuscript pages. The winner will be published in Issue 66 of Sonora Review; finalists will also be considered for publication.

c/o Poetry Editorial Board, Sonora Review, English Deptartment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85719. A cover letter with a brief biography and contact information should be included with submissions, but names should be removed from all manuscript pages. The winner will be published in Issue 66 of Sonora Review; finalists will also be considered for publication. Sponsored by the New York City–based literary advocacy and social justice organization

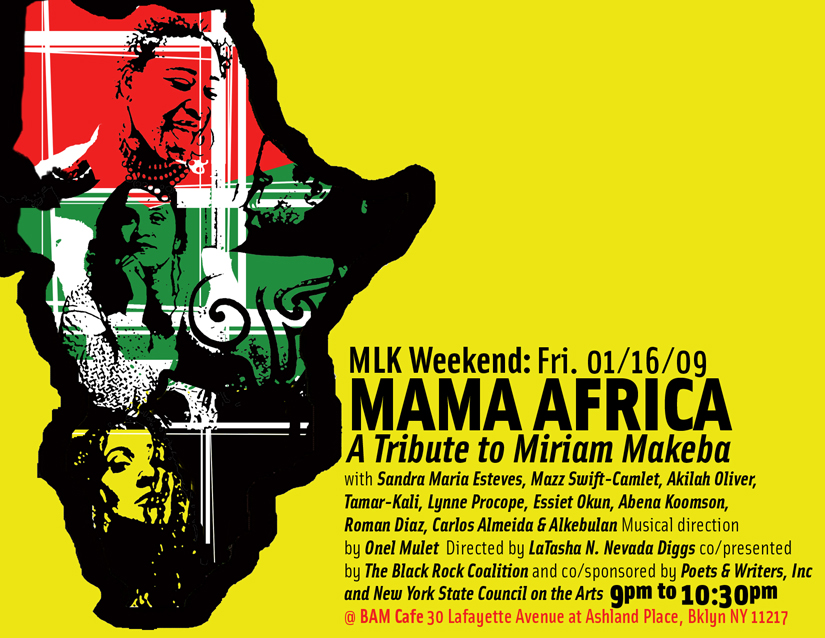

Sponsored by the New York City–based literary advocacy and social justice organization  “This must be one of the great historical moments for poetry, as there are so many thriving poetry presses, reading series, and astonishing new poems,” said Poetry Foundation president

“This must be one of the great historical moments for poetry, as there are so many thriving poetry presses, reading series, and astonishing new poems,” said Poetry Foundation president  The shores of California’s Salton Sea—a vast lake created when the Colorado River flooded salt mines in the Imperial Valley a hundred years ago—are littered with fish carcasses. Small as a child’s fist or large as a dinner plate, still shimmering with scales or dried to Halloweenish skeletons by the desert sun, they are a reminder of how delicate ecosystems are. The Salton Sea was a thriving resort community in the 1950s and ‘60s, but because it lacks a natural outlet, fertilizer runoff from nearby farms makes the water increasingly inhospitable.

The shores of California’s Salton Sea—a vast lake created when the Colorado River flooded salt mines in the Imperial Valley a hundred years ago—are littered with fish carcasses. Small as a child’s fist or large as a dinner plate, still shimmering with scales or dried to Halloweenish skeletons by the desert sun, they are a reminder of how delicate ecosystems are. The Salton Sea was a thriving resort community in the 1950s and ‘60s, but because it lacks a natural outlet, fertilizer runoff from nearby farms makes the water increasingly inhospitable.  It all began when Brandi M. Spaethe, an intern in P&W’s California office, took a road trip and fell in love with the odd, harsh beauty of the Salton Sea. She began wondering if other writers would be similarly inspired, and if locals might benefit from a literary event in an area that was hardly on many publishers’ book tours. She teamed up with Nolan, editor of the desert anthology

It all began when Brandi M. Spaethe, an intern in P&W’s California office, took a road trip and fell in love with the odd, harsh beauty of the Salton Sea. She began wondering if other writers would be similarly inspired, and if locals might benefit from a literary event in an area that was hardly on many publishers’ book tours. She teamed up with Nolan, editor of the desert anthology