If I conducted a brutal assessment of my reading habits—something I am not eager to do—the results would show that I spend an alarming percentage of my time rereading the same book: the 1965 novel Stoner by John Williams.

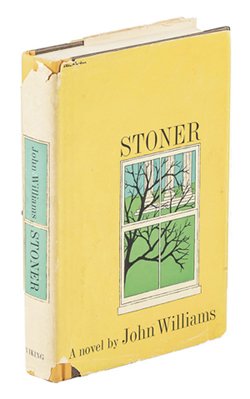

A first edition of Stoner, published by Viking Press in 1965. (Credit: PBA Galleries / Dana Weise)

As a reader and part-time book critic, I know I should focus my limited attention on the relentless tide of new and exciting work. But the decision to reread Stoner often feels more like a compulsion.

I’m not alone in this pattern. My wife, the novelist Erin Almond, has probably read Little Women as many times as I’ve read Stoner. A friend, the novelist and critic William Giraldi, revisits Wilkie Collins’s novels The Moonstone and The Woman in White on an annual basis.

I suspect every writer could tell a similar story. We return to our favorite novels for three distinct reasons.

First, for the sheer pleasure of entering into a familiar world, as we did in childhood, when we would delightedly read—or be read—the same story every night.

Second, because particular books serve as our literary mentors, directly influencing our own efforts, as in the case of Zadie Smith, whose 2005 novel, On Beauty, is, by her own enthusiastic declaration, a modern homage to the E. M. Forster classic Howards End.

Finally, and most profoundly, our favorite novels become manuals for living. We read them to be enchanted and inspired, to be transported out of ourselves but, most centrally, to know ourselves more deeply.

![]()

I found the novel Stoner back in 1995, during the first months of my MFA program, though it would probably be more accurate to say that Stoner found me. A second-year student pressed it into my hands at the tail end of a drunken party. I dutifully returned to my apartment and devoured it in a single night, which was not something I had ever done before.

What captured me on that first read was the novel’s earnest faith in the redemptive power of literature. The book’s hero, William Stoner, heads off to college hoping to discover new agricultural methods and rescue his parents’ farm.

In a required literature course, one of Stoner’s professors reads a Shakespearean sonnet, which sends Stoner spiraling into a reverie. Williams writes: “Light slanted from the windows and settled upon the faces of his fellow students, so that this illumination seemed to come from within them and go out against a dimness; a student blinked and a thin shadow fell upon a cheek whose down had caught the sunlight.” Stoner can suddenly feel the blood flowing invisibly through his own arteries. He regards his fellow students “curiously, as if he had not seen them before, and felt very distant from them and very close to them.”

A shiver was sent through my body as I read this passage, for I too had experienced an ecstatic awakening. It was the reason I’d fled a career in journalism to return to graduate school, a decision my editor regarded as foolish at best. (“You want to write books?” he sneered.)

As an apprentice writer and adjunct professor, I spent most of my time writing and teaching quite badly. I received a lot of rejection, all of it deserved. One particularly candid student noted on her teacher evaluation form that I was the worst teacher she had ever encountered. “If writing were a part of my body,” she added, “I would cut it off with a razor blade.”

Well then.

William Stoner also struggles as a teacher. He is often crippled by doubt, certain he’ll never be able to transmit his passion to a class full of uninterested students. But he also enjoys euphoric moments, when his love for particular works overruns his sense of inadequacy, and his students respond by showing “hints of imagination and the revelation of a tentative love” in their work.

Those were the moments for which I yearned in the classroom. And thus Stoner became a kind of homeland to which I could return amid my doubt, a world where the mission of writing and teaching literature felt unequivocally heroic. This is no doubt why so many writers and critics and professors champion the novel with such passion and persistence.

Stoner also affirmed my faith in the notion that any literary endeavor is ultimately a meritocracy. After all, the novel almost immediately went out of print following its initial publication in 1965. It was reissued, and went out of print, twice more, in 1972 and again in 2003. Each time, the evangelical fervor of readers persuaded publishers to give it another shot. The book finally went on to become a massive best-seller across Europe and was reissued a third time, in 2006, by New York Review of Books Classics.

Reading Stoner had an even more striking effect on my work at the keyboard. Like most MFA students I had been bludgeoned by the mantra “show, don’t tell” during my program, encouraged to write in scene as much as possible and to avoid sustained expository passages.

I had also come to believe that the key to writing exciting literature was to focus on memorable characters, the lawless and lust-driven, the drunken and depraved.

But from its opening words, Stoner put the lie to these dogmas. In fact, Williams begins the book with what amounts to a brief obituary, in which we learn that William Stoner taught at the same university his entire life, that he never rose above the rank of assistant professor and that “few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his course.”

This passage both riveted and confounded me. And it took me many years to figure out why. By upending our traditional sense of the heroic—that of external action and ambition—he was redirecting the reader’s attention to the true source of human drama, the inner life, that private set of yearnings and fears and confusions that are generally concealed from the world and yet persistently, unavoidably experienced.

Williams was also, almost invisibly, establishing an omniscient narrator who was capable of covering vast swaths of time and experience. It was this narrative latitude that allowed him to zero in on those precise moments when Stoner’s inner life is thrown into disequilibrium.

The novel was proof that leaping from one frantic scene to the next—show, don’t tell—did not render my work enthralling so much as unintelligible.

The more I studied Stoner as a writer, the more I recognized that its mechanisms of enthrallment were not obscure or mystical but straightforward and mechanical. The narrator builds psychologically and emotionally reliable ramps to harrowing moments and then slows down.

Because the action cannot move forward, the writer’s attention must turn inward, toward the chaos of unbearable feeling.

![]()

Although I’ve learned more about writing from reading Stoner than any workshop I ever took, the central reason I keep circling back to it isn’t aesthetic. What I’m after is personal reckoning. This is how it works with our favorite books. We turn to them precisely because they wield the power of intimate revelation.

Each time I’ve read Stoner it has illuminated some new aspect of my own inner life. This is what Nabokov means when he notes that “one cannot read a book; one can only reread it.” Literary fiction, by definition, must exhibit the depth to sustain multiple readings.

My initial, idealistic readings of Stoner quickly gave way to darker themes. Stoner, for instance, is dragged into a bitter dispute that derails his academic career. As a headstrong young author, I too found myself embroiled in rows with various agents, editors, and publishers. And so I read the novel as a study in human conflict, the ways in which Stoner unwittingly stokes his feuds, seeks to defend himself, and struggles to accept the limits of his power in the world.

When I was single, I regarded Stoner’s unhappy marriage as little more than proof of his stoic martyrdom. Later, a few years into my own marriage, I could see that Stoner was about something far more profound: the doom that awaits all couples who cannot find a common language to express their fears and desires.

Likewise, the moment I became a father I began to see Stoner as a grim parable about parenthood. Edith Stoner comes to her role as a mother having absorbed the abuse of her own parents, and she inflicts this abuse on her daughter, Grace. Her husband is too inhibited to protect Grace, and he watches, in silent agony, as his daughter descends into anguish and alcoholism.

That silent agony is shared by most readers. As should be clear by now, Stoner is not an easy book to read, particularly because its hero does so little to defend himself.

“Poor Daddy,” his daughter observes, as he lies dying, “things haven’t been easy for you, have they?”

“No,” Stoner responds. “But I supposed I didn’t want them to be.”

It’s a line that has echoed louder the older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve come to see the ways in which we conspire against ourselves. We pretend that our central desire is always the pursuit of happiness. But Stoner has no precedent for the joy he finds in literature and teaching, because his childhood prepared him only for a life of agricultural servitude. He has to make things hard for himself.

That sounds depressing. But our favorite novels—the ones that sustain us—are the ones that speak, with the most tender precision, to our own struggles.

As he drifts toward his final sleep, Stoner sees how pitiful his life must seem to others. But unexpectedly our hero awakens to find that a strange euphoria has suffused his perishing body. He dimly recalls “that he had been thinking of failure—as if it mattered. It seemed to him now that such thoughts were mean, unworthy of what his life had been.”

That may sound like a small triumph given all the hardship that precedes it. But this moment of transcendent grace is the reason I keep picking up Stoner, even twenty-five years later. Our favorite novels don’t just help us understand our lives. They are the path by which we travel in difficult truth toward an elusive mercy.

Steve Almond is the author of eleven books of fiction and nonfiction, most recently William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life (Ig Publishing, 2019).