If Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey gets a reboot, the soundtrack is ready: It’s 11 11 (Me Smiling) by Interplanetary Acoustic Team, the brainchild of Brian Turner, best known as the soldier poet whose bestselling Here, Bullet (Alice James, 2005) was the first salvo of poetic responses to the Iraq War. Turner, who served in Bosnia-Herzegovina before his time in Iraq, went on to write a second book of poems, Phantom Noise (Alice James, 2010), and the memoir My Life as a Foreign Country (W. W. Norton, 2014). His writing has garnered numerous awards, including fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Brian Turner and his late wife, Ilyse Kusnetz.

Turner’s latest turn of creative expression is entirely different—and it has everything to do with love. In 2010 he married poet Ilyse Kusnetz; three years later, just after the publication of her second book, Small Hours (Truman State University Press, 2014), Kusnetz was diagnosed with cancer, and on September 13, 2016, at the age of fifty, she left this life. But through 11 11 (Me Smiling), Turner has found a way to hold what he can no longer in life—his wife, in her poems and in her voice. The spoken-word album features Kusnetz’s words, most of them sung or spoken by her, mostly from poetry readings she had participated in, and some in the voice of Turner and others—all set to a landscape of sound that forms a lyrical and narrative journey.

I asked Turner more about this posthumous collaboration with his wife.

Brian, can you talk about the genesis of the project—both in terms of your passion for playing music in general, and the particular sound of this record, which feels interplanetary, not quite of this world, something that Sun Ra would have done for a Kubrick movie?

I had a strong stammer as a child, and I recognize now that a wild freight train of language had no means of escaping from my head—and my attempts at speech derailed whenever I tried to speak. My family moved from the city of Fresno to Madera County while I was in elementary school, and that move proved crucial to my development as an artist in many ways. Our new home sat between cattle rangeland and grape vineyards on a flat kingdom of dirt. It was a solitary existence. I practiced the trumpet out in the back yard, phrasing musical figures over waves of dead grass that stretched for miles.

That auditory landscape was as austere as the visual one, with a root note of silence. The end result is that I’m much more attuned to the auditory landscape than to the visual one. So it makes complete sense to me when you mention the cinematic quality of this album —as I find my way into story mostly through sound.

I want to get to the deep heart’s core of this project. I read it as a tribute and a way of keeping your love of your late wife, Ilyse Kusnetz, alive. In her words that appear in the second song, “Cyborg 3.0: Implant,” it’s as if “you can change suffering by reworking it through the imagination.”

I was separated from the earth when the idea for this album came to me. I was on a plane flying somewhere over the southwest, flying toward the dusk. My life made no sense at all, as Ilyse had been killed by cancer just a few months earlier. I was desperate in so many ways—and one of those included simply wanting to hear her voice. I wanted—as I still do—to find any means to continue being alive with her. I wanted to keep making art, to keep our conversation going, to somehow cross into the wide expanse of the cosmos so that we might continue to love each other.

I gathered all of the audio and video recordings of Ilyse that I could find. I then isolated conversations and poems connected in some way to what is, at its core, a very spiritual journey—though the surface level of the narration and soundscape seems focused on cybernetics, robots, computer code, and the uploading of human consciousness.

Along the way, I was assisted by a number of other artists: Benjamin Kramer, who engineered the album and played bass and some keyboards; Jared Silvia, who was part of the core of the album, playing modular synth; and Sunil Yapa, also a novelist, who added soulful, gorgeous guitar work. As with most artistic projects, there were many hands in the making.

Listen to “Light Sketch,” the eighth track on 11 11 (Me Smiling):

One of the things that struck me about the track “A Fundamentally New Idea in Synthesis,” and indeed the whole album, is the element of joy in it, a primal “coming-into-being” delight that contrasts with the grief experience as I understand it. In that song, your spoken words reference the Big Bang (“here is where our heart-fires start”) and ends with the heartbeat of a baby in utero. And similarly, in “Islands in the Cosmos,” the flowing water sounds like clapping, as if the universe were cheering itself on. Can you talk about the longing to go back to the origins of creation here, and how that longing is connected to the elegiac occasion?

Oh, I’m so glad you hear the clapping sound of the water! That’s spot on. To create that sound we took the sound of the audience clapping at the end of Ilyse’s book launch in 2014. I had this idea of transforming it into water somehow. I worked with Benjamin Kramer to layer that clapping and then we added effects to it until those cheering for Ilyse turned into a kind of waterfall, or cascade. In fact, whenever I’m at a literary event and people clap now, I hear the sound of water in it, as opposed to what I used to hear—a kind of echo of small arms fire.

All of the words and lyrics on the album are Ilyse’s (except for a couple of short passages from British scientist Kevin Warwick in the first song). In “A Fundamentally New Idea in Synthesis” I’m reciting verses from one of Ilyse’s poems—“The Explosion Museum”—from her poetry collection Angel Bones, forthcoming from Alice James Books in 2019. I’m trying to learn from her. In a sense I’m trying to cheat death, to undermine the fixed station we normally assign to the dead by giving them a terminal spot on the historical record, a gravestone to mark the occasion.... I don’t know if any of my attempts work, but I’m doing my best to refuse the elegiac impulse even though it exists deep within me at physical and emotional levels. That is, I want to upend the final movement within elegiac structures—those that come to rest or a conclusion based in solace or consolation. Solace and consolation are not enough.

Ilyse isn’t dead within me, and she isn’t dead within the world. I don’t claim to comprehend the universe or the possibility of an afterlife, but the similarities between birth and death are many. Each night we close our eyes and slip into the void of sleep, and afterward wake to discover the word now unfolding the day before us as the Earth travels through space at 67,000 miles per hour. My curiosity takes me to the nature of time itself. I want to explore the topography of space-time in the creative work I do.

Of course, Ilyse was already doing that. We can hear it in the words she’s given us.

That’s what I felt quite strongly throughout the work, that Ilyse’s words are almost imagining a posthumous existence. For example, in “Planetary Bird Engine” you include lines from her poem “Ideal City, Dream Sequence,” especially her transcendent ending:

but ahead, at the end of a narrow passageway

an eye-shaped aperture blossoms, expands—

all beyond its radiance invisible, composed of light,

and I wait, in the painted light, to step through.

Perhaps that was her poetic intuition, that she had a sense of mortality and what is beyond the mortal. In the final song, “Goodbye Earth/Goodbye Solar System,” there are echoes of Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon,” but the vision is far more benign and kindly. After all, the title of the work, taken from Ilyse’s poem, “Before I Am Downloaded Into a Most Excellent Robot Body,” notes that “11 11 is me, smiling.” Do you want to talk about her spirit here, her embrace of that unknown future?

I’m almost defeated from the outset by the very nature of verb tenses in English. We need to invent a new linguistic tool to express a wider range of temporal states, I think. Time out of time. That said, Ilyse was—and continues to be—incredibly brave and courageous. She realized the enormity of all that cancer was taking from her. Love. Beauty. Pain. Suffering. All of it. Her love for this world shines in the poems she’s left for us, and you can hear it in her voice when you listen to the album.

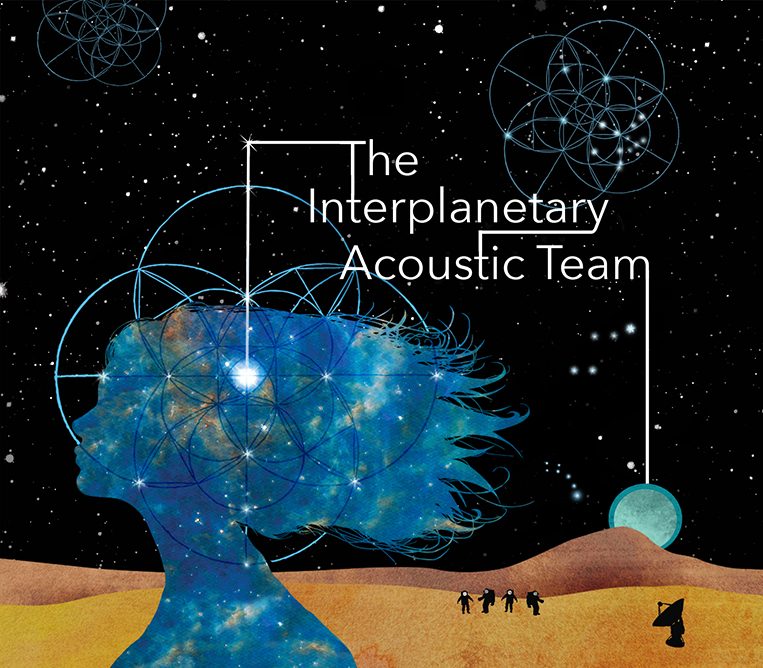

For more information about 11 11 (Me, Smiling) by the Interplanetary Acoustic Team, visit www.interplanetaryacousticteam.com or follow along on Instagram, @interplanetary_acoustic_team.

Philip Metres has written ten books, including Sand Opera (2015) and The Sound of Listening: Poetry as Refuge and Resistance (2018). Awarded the Lannan Fellowship and two Arab American Book Awards, he is professor of English and director of the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights program at John Carroll University.