In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 138.

People often think that to move your reader, you need to find the right idea or story, but the most effective way is to be moved yourself in the process of writing. I learned this lesson in clown school, which I attended as research for my book Animal Joy: A Book of Laughter and Resuscitation, published last week by Graywolf Press. For a clown, the equivalent of moving your reader is to make your audience laugh. The laughter occurs not because what you say is funny, but because it’s honest. If a performer’s expressions feel honest rather than rehearsed, the audience senses an authentic conversation, connects, and marks that connection with laughter.

In other words, it’s not only the content of what you bring onto the stage that has an effect, but also your relationship to what you bring. That’s because it’s not your material that the audience connects to, but the emotion you feel in relation to that material. For example, when a woman in clown school with me was on stage describing her love of eating chicken feet—particularly the sensation of moving the bones around in her mouth with her tongue—our class didn’t laugh because we thought her description was funny or clever. We laughed because we could sense the enjoyment she felt as she imaginatively enacted the process on stage. We connected viscerally with her pleasure—her genuine emotion—not with the idea of eating chicken feet.

But how does witnessing another person’s emotion provoke emotion in us? When we witness someone experiencing a strong feeling, that feeling is transmitted to us through mirror mechanisms in the brain, including mirror neurons. Mirror neurons allow us to feel the emotions of others inside ourselves as though they were our own. If you see someone cry, for example, your mirror neurons fire, causing the crying sensation to be mirrored within, so that you may even cry yourself. Because the same mirror neurons fire when we witness an emotion or action as when we feel or act ourselves, we are able to experience what happens outside of ourselves as part of our own subjective experience—to feel moved by experiences that are not our own.

That is why the most direct way for others to connect with your writing is by connecting with the emotion you feel in relation to the work. If you genuinely experience emotion within yourself during the writing process, that emotion will be transmitted to readers by way of mirror mechanisms in the brain. They will then experience your feeling within their bodies as though it were their own. “Indeed, a work of art,” writes composer Arnold Schoenberg, “can produce no greater effect than when it transmits the emotions which raged in the creator to the listener, in such a way that they also rage and storm in him.”

Accessing emotions that rage and storm in you is as much a psychoanalytic issue as it is an issue of craft. To lead with your emotions, it is helpful to avoid imitating your work that has been received well in the past, what you think your reader will like, or a voluntary idea. The psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion similarly advised psychoanalysts not to enter sessions with “memory, desire, [or] understanding.” This precept is repeated often in psychoanalytic circles, although most people drop “understanding” from the list. We are trained from our earliest days to lead with understanding: to have a thesis before writing a paper, an idea before pitching a piece. But what’s known is dead. “When you’re writing,” James Baldwin explains, “you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.”

To access genuine emotion, for your writing to be alive, it helps to soften your brain and let your impulses spontaneously express themselves. You shouldn’t try to control what comes out, even when it doesn’t align with how you’d like to be perceived. Sometimes our idea of ourselves—who we’d like to be, how we’d like to be perceived by others—can get in the way of becoming who we are.

Nuar Alsadir is the author of Animal Joy: A Book of Laughter and Resuscitation (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the poetry collections Fourth Person Singular (Liverpool University Press, 2017), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection in England and Ireland, and More Shadow Than Bird (Salt Publishing, 2012). She works as a psychoanalyst and psychotherapist in private practice.

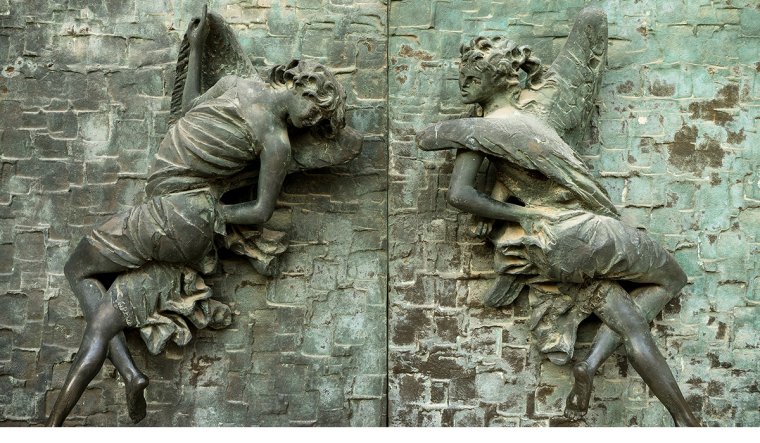

Art: Steffen Petermann