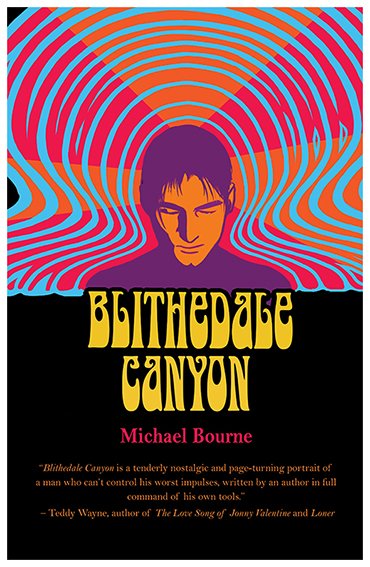

For more than a decade Michael Bourne has interviewed writers and publishing industry veterans as a contributing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine. This summer he will publish a book of his own, the novel Blithedale Canyon, a story of love and other addictions that novelist Teddy Wayne has described as “a tenderly nostalgic and page-turning portrait of a man who can’t control his worst impulses, written by an author in full command of his own tools.”

In “Going Solo: Selling Your Book Without an Agent,” which appears in the July/August 2022 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine, Bourne describes his long path to publishing Blithedale Canyon. After a number of near-misses with literary agents, he switched tactics and submitted the book directly to independent presses. Within months, two presses had expressed interest, one of which, Regal House Publishing, will publish it on June 30.

In the novel, one-time local baseball star Trent Wolfer has blown it, in every possible way, over and over and over. Now, fresh out of rehab and back in his hometown working a dead-end job at a fast food joint, he’s blowing it again, cutting out on his breaks to sneak airplane bottles of vodka and gin—until one day he looks up from his register to see his closest friend from high school, now a radiant blonde mother of two.

The following is an excerpt from the novel’s opening chapter.

“How come I only got five nuggets?” the skate rat at my register wanted to know.

It was straight-up noon, the line snaking out the double doors, machines beeping, fryers hissing, orders flying everywhere, but all I could think about as I made change and grabbed burgers and fries from under the heat lamps were the four Stoli mini bottles stashed under the passenger seat of my car. I’d popped off two before I clocked in that morning, and usually by now I would have ducked out back for a couple more, but our day manager Rajiv had written me up twice already for leaving my station without permission, and I couldn’t afford another blue sheet, which is what they called disciplinary actions at Howie’s Hamburgers.

The skate kid was fourteen or fifteen, loose-limbed and scrawny, acne pits deep as moon craters. Behind him his buddies were laughing. He’d passed a chicken nugget to one of them while I was topping up their sodas, and they wanted to see what I was going to do about it.

“There were six in there when I gave it to you,” I said.

“Do we need to get a manager here?” Zit Boy said, doubling down. “Because I’m seriously considering lodging a complaint. I paid for six nuggets, dude.”

The sad part was, I had been this kid not so long ago: the same filthy do-rag covering the same weedy splotch of sunbleached hair, the same battered skate deck and designer-label kicks that cost more than I made at Howie’s in a week. The effort it took to stay cool, to not jump over the counter and wipe that dickish grin off his face, was making my hands shake. I closed my eyes, trying to shut out the noise and the heat and the panic, but when I opened them again, he was still there, still grinning at me, waiting for me to lose it in front of the lunch crowd.

“Trent? Is that you?”

She had dyed her hair a streaky blonde and maybe put on a pound or two around the hips, but ten years later she was still Suze Randall. Old Pothead Suze. Except going by the cut of her navy-blue suit and the two tow-headed boys at her side, it had been a while since she’d seen the business end of a bong. She looked good. Better than good. Polished. Put-together. In her purse, you could just bet, was the key to a silver Beemer, or at the very least a frost-blue Lexus, two years past its warranty but so clean you could eat your lunch off the hood.

The skate rats drifted back from the counter, sipping their sodas, fascinated.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

“I’m buying my kids some lunch,” Suze said. “What’re you doing here?”

Zit Boy giggled and she shot him a look that sent the four of them skittering off toward the dining area, chomping their fries and chucking each other. But now my register was free, and she had no choice but to step up to the counter. The two boys had gone still, twigging that Mom was deep in the weeds and didn’t know how to get out.

“I didn’t know you were back in Mill Valley,” she said.

“You, either,” I said. “I thought you were still in L.A.”

“I was, till a year ago. Then I moved back.”

I nodded, speechless. This was the first time all summer I had run into anyone from the old days and I wanted to crawl into a hole. But there was no hole to crawl into, nothing to do but stand there watching Suze try not to stare at my greasy hair stuffed up under a plastic hairnet.

Rajiv was watching us now from his seat at the drive-up window, so I said, “You know, maybe I should take your order.”

Seeing Rajiv, Suze hustled through her order: two Kiddie Meal Deals with everything for the boys and a Lean Meal Deal for her, hold the Howie sauce. I rang it all up and got the drinks and the kids’ food, but thanks to the special order on her veggie burger we were stuck at the counter for an extra minute. It felt like a day and a half. The last time I’d seen Suze we were both in college, sort of, me at UC Santa Barbara, Suze at Cal State L.A. Suze had dropped most of her classes and was living in Pasadena with her boyfriend Jimmy Strasser, and I had gotten kicked out of the UCSB baseball program for trying to start a mini grow-op in my closet in the dorms. Still, nothing about the kid I was back then quite added up to this: a twenty-nine-year-old white guy working the register at Howie’s Hamburgers.

“They have to grow the soybeans,” I said.

“Huh?”

“Out back,” I said, wishing I hadn’t started on this. “That’s why it’s taking so long. They have to grow the beans first.”

“Oh, right,” she said, and laughed. It wasn’t funny, to her or me, but the way she laughed, the old Suze way, waving her hand in front of her face like she was putting out a fire, flashed me back nine years, to the very last time I saw her. She had called me in the dorms, drunk and babbling, saying Jimmy had cheated on her again. I borrowed my roommate’s car and drove to L.A. to comfort her, just like old times. And what happened then? Jimmy called is what happened then. By eight the next morning, Suze and Jimmy were having window-rattling makeup sex and I was bombing through Oxnard on my way back up the coast.

When Suze’s veggie burger arrived, I slipped it into the sack and handed it to her across the counter. The fluorescent lights were like ten thousand needles pressing on my eyeballs, and I needed that Stoli hit, bad. But she didn’t move, not right away.

“I saw your mom the other day,” she said. “She’s with that guy now—what’s-his-name, the eco-patio-furniture guy.”

“That would be Stan Starling,” I said, sneaking a peek at the third finger of her left hand. My pulse skipped a beat: no ring.

“Mom, let’s go,” the older boy whined, nudging her.

“Hang on, Dylan. Mommy’s talking.” She turned back to me. “Your mom was at some thing, a charity thing at the tennis club. In fact, I think she was running it.”

She said more, but I was staring at little Dylan. The wash of freckles, that jutting jawline, the thatch of strawberry-blond hair: there was only one man on earth who could be this kid’s father, and that man was Jimmy Strasser. I peeked again at Suze’s left hand: still no ring.

“Is everything all right, madam?” Rajiv asked, swooping in out of nowhere.

Suze gave him the slow elevator eyes. “Everything’s fine, thanks.”

“She’s a friend from school,” I said. “We were just talking.”

Rajiv was slight-built and pale, his eyes a blackish, oily color. I’m not good at ages, but if you’d put a gun to my head I would’ve said twenty-two. No razor had touched that delicate chin. If it weren’t for the clownish Howie’s manager’s uniform with its blue wool-knit tie and oversized lapels, he might have even been handsome in a geeky, science-camp-kid kind of way.

“I see that,” he said. “I am thinking only of our other customers, who are waiting.”

“Where were you a minute ago, then?” I said, loud enough to cut through the lunch-rush din.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Some kids were hassling me at my register. They were holding up the whole line, and you didn’t move a muscle. So how about you give me one minute to catch up with an old friend?”

Suze smiled, and the world’s tiniest helium balloon of self-respect inflated in my chest. But then I saw Rajiv’s hairless chin wobble, and I realized that, stupid, stupid me, I’d just caught my third and final blue sheet.

“It’s okay,” Suze said, grabbing her bag of food. “We were just leaving.”

“Very well, madam,” Rajiv called after her. “Enjoy your meal!”

But she was already gone, striding out toward the parking lot, her two boys half-running to keep up. Rajiv cleared his throat, gave that ridiculous blue tie a tug, and marched back into the kitchen. The kid at the register next to mine kept his head down, smirking as he made change from his drawer, but from behind the order window I heard the day cook LaShonda’s hissed catcall: “Tell him, white boy!”

I was halfway through keying in the next customer’s order when a fleck of white caught my eye on the counter next to my register. It was a business card, a fancy one, cream-colored with raised blue lettering and the embossed logo of a local real estate firm. It read,

SUZETTE R. STRASSER, REALTOR®

and listed four phone numbers: office, cell, pager, and home.

From Blithedale Canyon by Michael Bourne. Copyright © 2022 by Michael Bourne. Published by Regal House Publishing. www.regalhousepublishing.com