Ten more years on the job and I’ll unlock those benefits; just a little more time and I’ll get that raise. It’s a calculation most of us have made and one that anchors the protagonist of Shane Jones’s latest novel, Vincent and Alice and Alice, out this week from indie press Tyrant Books. In this comedic office novel, Vincent works as a mid-level pencil pusher for the state, which offers premium benefits and a handsome retirement package. When Vincent is not thinking about retirement, he’s dreaming about Alice, who he recently divorced. When selected by his manager for an experiment to increase worker happiness and productivity, Vincent eagerly agrees, only to realize that his happiness is inextricably linked to his ex-wife.

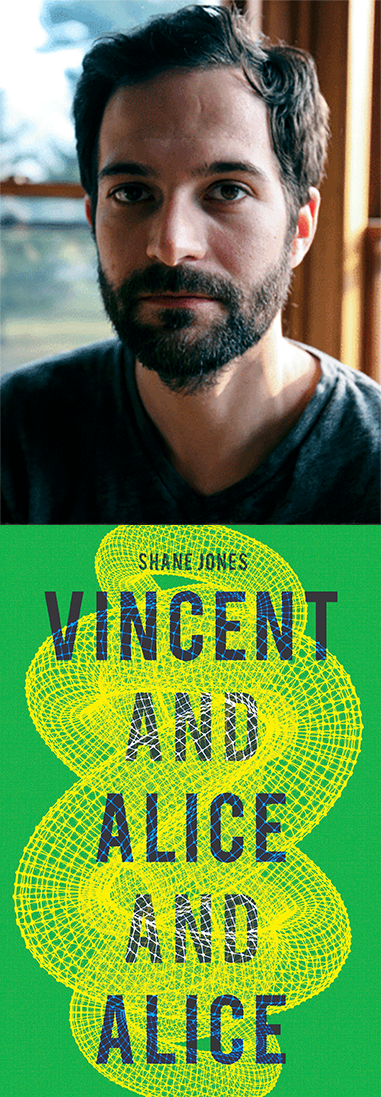

Shane Jones, author of Vincent and Alice and Alice. (Credit: Erin Pihlaja)

Shane Jones has a long history of working with indie presses. Publishing Genius published his first novel, Light Boxes, in 2009. After it generated eye-brow raising sales, especially for a novel published by a small press, Penguin republished it a year later, and in 2012 released his second novel, Daniel Fights a Hurricane. But sales did not meet expectations and, after mounting frustrations over the business of commercial publishing, Jones bypassed his agent and returned to the indie circuit. Two Dollar Radio released his third novel, Crystal Eaters, and now Tyrant Books has published his fourth.

Jones recently spoke about the challenge of plot and character development, the pros and cons of indie publishing, and what new risks he took in Vincent and Alice and Alice.

The tension between reality and fantasy is a recurring theme in your novels. What sustains your interest in the relationship between reality and fantasy and how would you characterize that dynamic in the new novel?

To me reality seems so fucked and strange to begin with. The idea is to blend the fantasy and reality in a way that brings the reader into a new world. This book, probably more so than the other books, achieves that, at least I hope it does.

The dynamics between reality and fantasy have varied in your past novels. Did you approach this book from a specific angle?

I wanted to write a mainstream book.

In past interviews you talked about wanting to move away from pretty imagery and toward something with more emotional traction, which I think speaks to the ambition of wanting to write something more mainstream. By writing a novel about work life in a bureaucratic office were you teeing up that challenge?

Absolutely. I think a lot of writers, almost anyone, can write pretty sentences and nice images. It doesn’t take you that far. To actually tackle plot or character development, things that I would have never tried eight or nine years ago, is really difficult. People knock—and I’m guilty of it too—what’s considered realist fiction, but it’s really hard to do. When it’s done well, the payoff can be greater than a pretty image, which can shock and awe readers but also keeps them at a distance.

You’ve mentioned before how your writing process has changed, that you’ve slowed down and tried to be more deliberate and less “reckless,” as you’ve put it. Has your revision process changed as well? How did that play out in the case of Vincent and Alice and Alice?

This book was definitely written more slowly, but in a more conscious way, where I was constantly telling myself to slow down and really think about sentences. In past books, the word I would always concentrate on was push. Constantly moving forward and trying to get as many words down as possible.

I’ve always done a ton of revising. I revised this one probably more than the other books. Just going over and over and over, sentence by sentence. There were days when I would spend seven or eight hours on just a couple of paragraphs, which is something I didn’t do before.

When you talked about wanting to focus more on plot and character development. How did you approach that?

I think the conceptual idea of Alice re-appearing is central to the plot development. The plot kind of spins off that moment, in both directions. Having to build up to that moment and what happens after that is the plot. I kept looking at Fight Club, which was a book I would never have looked at before. The novel is really fast. The sentences are really close, intimate, visceral. But it’s also a book that is kind of weird and imaginative while coming off as somewhat mainstream or accessible. It’s a book all about action and build-up, which is basically the plot, and those are things I wanted in my book. Fight Club always has something lurking around the corner, it pushes the reader forward, doesn't get bogged down in language. Where before I would look at a book like, I don’t know, something by Brautigan, to get moving, I just thought of the most mainstream work of fiction I could get into, and it was Fight Club.

Were there other books you turned to for plot or character development?

I remember looking at Lightning Rods by Helen DeWitt just because it’s an office novel that is really funny and imaginative, qualities I admire and respect. The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark was another book that had an impact.

Something I think you do really well and I’m always curious about is world-building. When it’s done well, readers are introduced to these worlds and their logic, not by exposition, but in the course of a character walking across a room. Could you talk about some of your strategies when introducing readers to new worlds?

Being fully immersed. To the point where you’re really not thinking about anything else. I have a day job, but I was working on the book throughout down times in the day job. I put almost everything off personally, at the expense of my marriage, my relationship with my son. I pretty much stopped all my friendships. If you really want to know, it’s just full immersion.

You’ve worked with several notable indie presses—Publishing Genius, Two Dollar Radio, and, now, Tyrant Books. What have you most valued about working with these publishers?

Control. Having more control over the editing process, figuring out the cover, and promoting the book. Second, it feels a lot more fun with indie presses. With a big publisher, it’s always felt like a job or a business. With that business you get more money and marketing, and you can tell strangers and family members the name of the publisher and they immediately recognize it. With small publishers people discredit it right away or don’t understand. They think you’re paying to have it published.

What are the drawbacks to working with indie publishers?

Distribution and money. Those are the two big ones. They don’t have the same distribution power or promotional power, and you’re not going to get paid the same amount. It’s also an ego thing. It’s nice to say you’re published by Penguin. I remember telling people about Publishing Genius — I remember thinking they were the best publisher at the time and I didn’t even go to any big publishers or agents—people had no idea what Publishing Genius was. When Light Boxes came out from Penguin, people immediately recognized it, which was an ego trip. It’s good to be humble. I think it’s important to be a grunt and work hard. That’s how I feel with Tyrant. Gian [Giancarlo DiTrapano, the publisher of Tyrant Books] is amazing in pushing his writers.

When you were sending around VAAAA, did you even consider bigger publishing houses or did you stick to the indie circuit?

I definitely did. Like I said, I wanted it to be a mainstream book. There were people that wanted it, and then when they sent it to the sales department they saw my past sales, especially for Daniel Fights a Hurricane, and immediately the book was rejected. So after a certain period of time, I just sent it to Gian myself and didn’t tell my agent. There was no synopsis or anything, I just said, “Hey, I have a book, do you want to read it?” He wrote back, “Yeah.” And then he took it two weeks later.

When you decided to e-mail Gian, was that because you had a personal relationship or because you’re following the indie scene.

I’ve only met him twice so we don’t really have a close relationships. I just think they were doing the most interesting books and still are. The stuff he’s been putting out the last couple years, since the Atticus Lish book [Life Is With People] it’s unbelievable. It felt right, and I have a lot of respect for what he does.

What advice would you offer to someone shopping around their first manuscript? And does that advice change if someone is aiming for the indie circuit versus a big publishing house?

That’s a really good question. I don’t know if I’m the right person to ask because I’ve been all over the place. It depends on what you want. I think most young writers want the big contract. It’s an ego thing. If I really ask myself deep inside what I want, Tyrant Books makes the most sense. That’s where my book should be. That’s where it feels most at home. “Ground your ego” might be good advice.

The whole thing is a game. If you really want to play the game, get the biggest, best agent you can. Start networking. People that get publishing deals develop friendships with editors. These are people that go to each other’s weddings. So if you want to play the game, then play the game. But I think going indie publishing can be the way to go too.

Connor Goodwin is a writer and critic from Lincoln, Nebraska. His writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Review of Books, BOMB Magazine, Fanzine, the Rumpus, Modern Painters, X-R-A-Y, and elsewhere. He is working on his first novel.