Hilary Leichter’s debut novel, Temporary, published this week by Coffee House Press (the final title on the publisher’s Emily Books imprint), follows a temp from placement to placement. She is given sky work and blood work, paper work and home work, all the while hoping for a permanence that eludes her. Her journey is both universal and specific, both utterly fantastic and entirely real. In Hilary’s writing, it is possible for a single narrative to be all of these things.

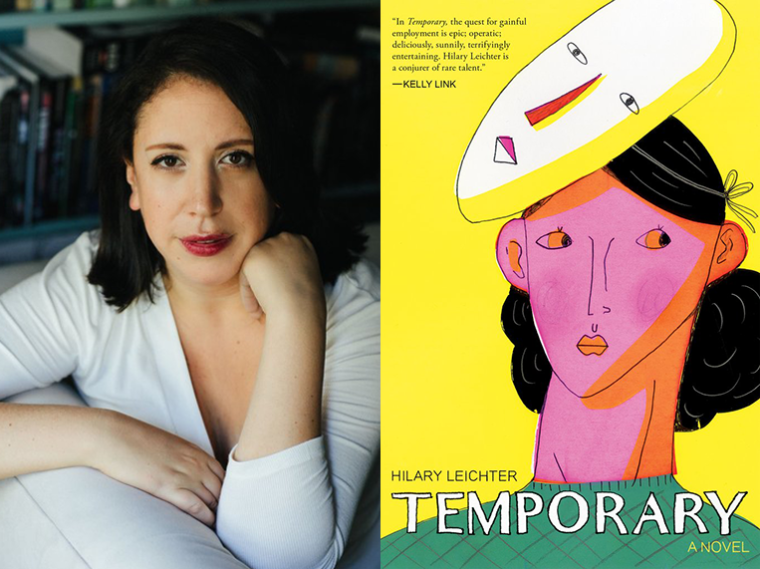

Hilary Leichter, author of Temporary. (Credit: Sylvie Rosokoff)

Hilary has an ear for the oddness of language and an eye for the strangeness of life. I first came to know this from her “eggcorn” stories, one of which I had the honor of publishing in the literary journal Joyland. In these, she takes a snippet of misspoken language—as in, a “far gone” conclusion or a “statue” of limitations—and mines it for the emotion and logic therein contained. The resulting short tales are playful and profound.

If each “eggcorn” is a microdose of her magic, then Temporary is an intoxicating enchantment. With wit and with heart, Hilary weaves a workplace narrative into a fairy tale’s form to transport the reader. In the world of the book, characters must work to live and professions dictate personhood. In other words, it might be our world. In Hilary’s words, it both is and is not.

Reading Temporary, I was reminded partly of other narratives of work, like Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris and Helen Phillips’s The Beautiful Bureaucrat. What made you want to write a narrative about work? What brought you to tell this tale of a very specific kind of work: temporary work?

I’m so glad to be lingering on the edges of the marvelous and ever-expanding Canon of the Workplace. I drew quite a bit of inspiration not only from my own jobs, but from the heightened camp of movies like the musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and the zany, Sisyphean “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” sequence from Fantasia—those multiplying brooms! I hoped for the book to have enough room to contain both the cartoonish and the catastrophic, because my experience of employment has often encompassed both.

When I started writing this novel, it was a short story. I was knee-deep in a paycheck-to-paycheck existence, working several jobs at once and finishing my thesis for graduate school. All of the writers around me were in similar boats. We were waving to each other from our boats. I worked as a temp at a property management company. I was also teaching undergraduates, working as an assistant, and tutoring three young boys. There were certain days when I’d forget where I was supposed to be, and when. I don’t think there’s anything unique about this scenario. It feels typical. One of the best parts of writing this book has been hearing about people’s work, the varied assortment of tasks—some mundane, some extraordinary—that constitute a paycheck. And so, I wanted to write about how impermanent work impacts the soul, how a sense of belonging, as it pertains to work, had eluded me and so many of my peers. And how this sort of displacement might speak to a greater sort of displacement, a question about the necessity of people, of our existence. These questions allowed me to create a version of this world slightly shifted on its axis, where employment is the fulcrum on which a life soars or dips.

What role does humor have when it comes to what it is that we “do” with our lives? What about tragedy? I ask because I laughed and I cried while reading Temporary, which I fear might sound trite but is simply true.

I think life is entirely absurd. It’s preposterous that I’m sitting here making words with my fingers on a keyboard. It’s preposterous that I’m doing this, while horrible things are happening everywhere, all over the world, this very minute. Even in this room where I’m typing, tiny cells are living and dying and living and dying. Germs are existing and then getting doused with Clorox wipes, on the very screen where I can see these words appearing. I find the simultaneity of emotion absurd. I also find it devastating, and I would say that my life is ruled by hilarity and sincerity in equal measure. A failure to capitulate to both of these gods results in a temporary collapse of my personhood. There’s no way for me to make it through a simple commute without matched doses of sincerity and hilarity.

As it pertains to work, I find that the more ridiculous the task, the more pathos it secretly contains.

Your main character is constantly replacing someone else. What freedom did you find in crafting a character that is, by necessity, a bit of a chameleon? What challenges did this present?

The narrator’s identity definitely required a sort of sustained malleability. This is what allows for her to be a temporary, to easily shift in and out of the roles she is asked to fill. In the mythos of the book, “early” temporaries were so malleable that they could physically mold themselves into bowls, moons, shoelace trimmings, horizons. This flexibility also gives her a different kind of morality—she’s not amoral, but she’s perhaps post-moral. Her versions of right and wrong are sometimes different than ours, but not for lack of conscience or desire to do good. The good of her world is a different kind of good, and the world that contains that good is also different.

So even in my very first imaginings of this character, she did not have a name, or an age. I sometimes like to picture her as a young professional, other times, as someone much older, who has been at this grind for longer than we can imagine. She contains both versions. In a way, her identity is an amalgamation of all the identities required of her, and it was a great deal of fun watching her edges grow bolder and more distinct with the completion of each chapter. But it’s difficult to get specific with a character who evades specificity—what do they call a jack-of-all-trades in business jargon? A “generalist”? She’s a generalist, and that’s the enemy of delicious, precise language. So I tried to sink as fully as I could into the problems of the general, of this chameleon-hood, these feelings of being untethered from selfhood, and how this fluidity perhaps has a language and specificity of its own.

The narrator does have a characteristic capacity for empathy that intrigued me. It is enormous! It extends to people who treat her terribly and even to inanimate objects. In a world where employees are expendable and people replaceable, is her empathy a superpower or a weakness?

I think that superpowers are often also weaknesses. She can put herself in someone else’s shoes, but she can’t take those shoes off. She has to walk in them forever. Which provides a certain degree of emotional insight, and also a certain number of blisters. The writers I most admire treat their subjects the way that the narrator treats her world. Whether consciously or not, I know that to some extent I was writing about writers, about us.

From our time editing the journal NOON and from reading your short stories, I know that you love to play with the sound of language at a word and sentence level. In Temporary, I found that beautiful prose and playful language. But I’m curious what had to change as you expanded that style into a book-length work?

NOON was a masterclass in editorial marksmanship. It was endlessly fun and instructive watching Diane Williams cut to the heart of a short story, or maybe expose a ventricle that the author had not noticed, simply by adjusting the placement, order, and sound of the sentences.

The hardest thing about writing a novel was that I couldn’t hold it all in my head at once. So many of my short stories are very, very short—a few of them are just a sentence long. It’s a different sort of task, building a maze that takes up the space of a single page, versus building a maze over the course of many, many pages. That’s how I approach writing stories, and now novels—puzzles built from language. It’s the recursion and linking of sentences that allows for plot, character, and momentum to occur. Since I could not hold the entire puzzle in my head while writing Temporary, I would keep a constant running list of moments to readdress, parenthetical reminders throughout the text for areas that needed folding back or stretching forward.

But more than just playfulness in language, I’m obsessed with moments where language fails. A misunderstood bit of language is, on some level, a failure to connect, a missed signal, a fraught and lonely signifier of the human condition. I feel a constant urge to repair this rift. To swoop into the space where human connection breaks, and muscle that space into prose.

I tried to take some specific office totems—human resources, coffee mugs, boardrooms—and spin them around until they revealed a violent or sentimental or dangerous underbelly. One phrase that I learned after finishing a draft of the book: “managing up.” I am delighted by this phrase. I can’t help but picture a temporary climbing some sort of corporate ladder into the clouds.

Can we talk about the book’s structure? The novel is broken into episodic sections that follow different placements she is given on her search for “steadiness.” How did you land on this structure?

The structure remained completely hidden to me until I had finished writing. At that point, I saw that there was a quest-like quality to the plot, and I started to think of each job as a giving the narrator some sort of magic element that allowed her to move forward. I’ve just revealed my brain as a straight-up product of horcruxes, video games, and fairy tales.

How and when did the ending reveal itself to you?

I’ve rewritten the ending nearly a hundred times, but it has definitely retained some of what I always wanted it to have from the very first draft. But there’s a penultimate “ending,” a twist that I didn’t know about or plan until I was very deep in the mess of writing. And then it conked me over the head and helped to shape the entire book. I love being conked over the head, but only metaphorically!

There are several stories within the larger quest story that thread through: the myth of the First Temp, memories of her mother and grandmother. How did you balance these elements with the relentless forward progression she has to take from placement to placement?

I needed them! I need pitstops. I grew up off of I-95!

I love interstitial narratives. They have a nonessential quality that makes them completely essential to me. I am always a fan of a recurring side character on a TV show who finally gets that one perfect episode written entirely from their perspective.

I wanted to create a real, solid mythology for the world of Temporary, and I ended up turning to books like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves for clues on how to execute that kind of structure. The chapters that involve memories of the narrator’s family also center around work. If you look at the book as a resume, an application for “permanence,” those memories are perhaps important to understanding her employment history.

Many of the narrator’s jobs reminded me of Penelope’s weaving and unweaving in The Odyssey. She opens and closes doors, distributes and collects pamphlets. Many of the temps in the book are women, and the narrator inherits the work matrilineally. What about temporary or invisible work has belonged to women? Thinking about the men of the novel: What was important to you about their inclusion in this story?

I wish I could claim that I was considering Penelope the entire time—what a wonderful connection to make. I am working on a novel right now that ties back to The Odyssey, and so this is definitely on my mind, if only in the recesses.

But yes, I was constantly thinking about the invisible work of women while writing this book. The weaving and unweaving of our contributions to society, to families, to the world. I’ve read a lot of essays about the “emotional labor” that women do, not only at work, but for everyone in their lives. A marvelous phrase: emotional labor. How can labor be anything other than emotional? This is the question that I hoped to ask. If that question is the first part of a call and response, then the response I wrote for my book was “There is nothing more personal than doing your job.”

And yes, for me, that call and response was specifically about women, and about our place in the world, a place that’s often shunted off or sealed shut. But I think anyone, no matter their gender, can have the experience of feeling undervalued. And so it was important to me to include some male temporaries, too. They’re all in it together, struggling with a system rigged against their survival.

Rebekah Bergman is a fiction writer living in Brooklyn. She received her BA in literary arts from Brown University and MFA in fiction from The New School. Her stories have appeared in Tin House, Hobart, Joyland, and Cosmonauts Avenue, among other journals. She is at work on a novel.