A writer’s library is more than just a collection of books. It is also a piecemeal biography of that writer’s life, and measurably so, as most writers have spent countless hours reading the books that they own or have borrowed, hours that add up to years, perhaps decades, given a long-enough life. My library, accumulated over the past sixty years, makes perfect sense to me: It is a living illustration of my life, which may or may not have to do with killing time, literary value, collectability, books as attractive objects, information, and nostalgia. It has served as a barrier against the howling chaos that complicates the world. It has no apparent rhyme or reason: a labyrinth of eccentricities. Its monetary value is literally incalculable, since it’s essentially a storehouse of memories that are worth a fortune to me, and yet it’s true that the vast majority of the books in my collection were bought cheap from used bookstores. No two writers’ libraries are alike, and it’s interesting what you can discover about a writer’s life simply by looking at the books the writer has elected to keep on hand.

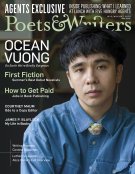

The author’s book-filled study. “My favorite books are kept in my study, under the stairs in my house,” he writes. (Credit: Danny Blaylock)

Not long ago I was reading a collection of essays by Hilaire Belloc titled One Thing and Another, and, as is sometimes the case when I read other people’s essays, I got the idea of writing this one. The “idea,” such as it was, had nothing to do with the subject matter of any of the forty essays contained in Belloc’s book; what struck me was that the pages smelled as if they had been soaked in gasoline. I remembered abruptly that it had smelled that way when I’d bought it, and although it has sat on the shelf in my study for twenty years, waiting to be read, the odor hasn’t diminished. It could be fatal to light a match anywhere near it.

This olfactory discovery sent me off in a nostalgic search for my copy of Philip K. Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney, which Phil gave to me in 1975. My wife, Viki, and I took off on a road trip a few days later in our old Volkswagen Bug, and I brought the book along. It mysteriously disappeared early one rainy morning in central Canada, and I didn’t find it again until a year later, after the car’s battery died. The VW’s battery was under the back seat, and when I pulled out the seat to get at the battery, there was Dr. Bloodmoney, its cover partly eaten by battery acid. I was monumentally happy to find it. The book is inscribed to “Jim Blaylock, a hell of a neat dude,” the only existing written evidence of that allegation.

Looking at the book again called to my mind elements of the wild storm that our cotton tent weathered on a hilltop between Winnipeg and Regina on that long-ago road trip and the landscape along Lake Superior and down into Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. Viki and I took turns reading The Wind in the Willows aloud while the other one drove—the 1960 Scribner edition with maps on the end pages and both color and black-and-white illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard. I’ve reread it two or three times since. The bookmark advertising the bookstore where we’d bought it still lies safely inside: Austen Books, 1687 Haight Street, San Francisco. It’s one of the thousands of quirky bookstores that have vanished over the past decades, leaving no traces aside from dwindling human memories and paper bookmarks.

A canny reader might point out that I’m confusedly considering books as objects while failing to consider the contents, and of course I am, except that there’s no actual confusion involved. Unless books are read in various translations, the contents are pretty much the same for every reader, and an e-book will serve the purpose as well as paper and ink. As is true of angels, ten thousand e-books can dance on the head of a pin, which some readers see as an advantage. But that’s the only angelic thing about invisible books. Even en masse, e-books cannot add up to a library. An e-copy of a book cannot smell of gasoline or be disfigured by battery acid and so is inarguably imaginary and not a proper book at all. An e-reader crammed with such “books” is merely a bucket of electrons, and it’s a little-known fact that if you shake your e-reader too hard, the words will simply collapse into heaps of letters. A cardboard bookmark has more substance.

![]()

Back in the 1970s I took to buying two copies of every “important” book that I could get my hands on—literary novels and collections of essays and stories and poems; that is to say, books likely to be recommended by university literature professors notorious for insisting that their students think. I was a political creature in those days and worried that the Forces of Ignorance would someday see fit to burn books in the street. It seemed sensible that I should squirrel away my hardcover books in the crawl space beneath the house. I’d keep my paperback reading copies of the same books in plain view on the shelf. When the dreaded day came, I’d hand over hundreds of visible books, weeping convincingly and promising to propagate stupidity rather than a library. My plan hit the reef, however, when it dawned on me that I’d be able to own only 50 percent as many books as I might own otherwise, and so my political motivation collapsed under the weight of book greed. I sent ten crates of the second copies to the Palisade High School library in Colorado, where my cousin Tom was teaching. That opened up shelf space in my own library, thereby creating a vacuum that immediately began to fill with more books.

I’ll admit that I didn’t mention this notion of storing books beneath the floorboards to Viki, who might have considered the idea peculiar. Throughout our marriage she has cheerfully abided by a nonaggression pact concerning my books. She’s an inveterate reader herself, but she sometimes wonders how many thousands of books a person needs. “O, reason not the need,” I tell her, quoting King Lear’s plea to his daughter Regan a short while before he goes stark staring mad. It’s true that there’s a faint line between the bibliophile, who treasures books for rational reasons—for their monetary value or literary value, say—and the bibliomaniac, a bibliophile who, as P. G. Wodehouse put it, has gone off his chump.

A number of people over the years have asked whether I’ve “read all those books,” when they cast their eyes on my library. To my mind that’s a little like asking salt-and-pepper shaker collectors whether they’ve filled their eight hundred shakers with salt and pepper. I answer the question by pointing out that I’m not dead yet, which is factual but not altogether truthful in what it implies. I have no intention of reading all my books, although I might tackle any one of them tomorrow. In fact I tackled one today, Robert Graves’s autobiography Goodbye to All That, which I first read in 1976. It turns out that it’s even better than I remembered, although it’s possible that, as C. S. Lewis wrote, “being now able to put more in, of course I get more out.” It’s true that rereading further reduces the chance that I’ll read the rest of the books in my library. If one is simply trying to get through a shelf of books as if eating one’s way through a loaf of bread before it molds, the backward step of rereading brings about a variety of Zeno’s paradoxes.

In any event I thought I would read all my books back when I bought them. Some I’ve insisted I would read, although it turns out that the more insistent I become, the less likely I’ll actually do so. Every summer I decide to reread The Pickwick Papers, and I make it about halfway through before the summer ends. I’ve taken to bookmarking the best chapters and rereading those, which compounds the problem, because I never really get anywhere, and yet I’m satisfied with the result. And every decade or so I decide to tackle the single-volume collection of Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, a twelve-thousand-page rat whacker. I admit that I’ve failed. It turns out, alas, that I get lazier with age, and recently I made a firm decision to save the Joseph quartet for deathbed reading, simply for the fun of keeping the grim reaper fidgeting in a bedside chair, picking his teeth with his scythe while the reading drags on. Like Charles II, I’d apologize to him for taking an “unconscionable time a-dying.”

In the 1970s and early 1980s I used to make regular runs into Long Beach, California, with Tim Powers, friend and fellow writer, to spend a couple of hours wading through the stacks at Bertrand Smith’s Acres of Books, which allegedly held well over a million volumes. It was impossible to find any particular book, but finding a book that you suddenly had to own was inevitable. On one trip I stumbled happily upon a signed copy of the Collected Poems of Alfred Noyes for fifteen dollars. That one emptied my wallet, which was fairly thin back then. Neither of us had much money—ten bucks, say, maybe five—but that would often score us a paper shopping bag full of books. We’d temper our spending to have a few bucks left for a beer and sausage sandwich at Joe Jost’s, our favorite bar.

I was a fan of William Gerhardie’s novels in those days and still am. Gerhardie was proclaimed a genius by H. G. Wells, Evelyn Waugh, and Vladimir Nabokov, among other luminaries. His star was at its zenith in the 1920s. After World War II, however, his books became “unfashionable” (the bane of writers), and he died in obscurity. At Acres of Books I paid two dollars for a copy of Gerhardie’s Pending Heaven, inscribed “To Madeline, New York, 1930.” I wonder sometimes what happened to Madeline. Did she value this copy of Pending Heaven as much as I do and keep it on the shelf until she died, or did she sell it when Gerhardie’s signature was still worth something? How did the book find its way to Long Beach? Why the cheap two-dollar price for a signed first American edition of the book? Are all books destined to go out of fashion?

If I had to run from a fire carrying only ten books, my signed copy of Pending Heaven would be among them, although I can’t begin to justify saying so: mere sentiment, nostalgia, nuttiness. It’s entirely likely that whoever has to shovel my books into trash bins after my death will not give the book a second glance, or a first glance for that matter, and it’ll go the way of all flesh, taking a remnant of Madeline (and me) along with it.

It was at Acres of Books that I bought my first book published with uncut pages. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when such books were popular, readers needed a knife to cut open the pages as they read, which is an adventurous idea. The trendiest knives were often dull, letter openers or butter knives that would leave a particularly ragged edge as if the book were made of handmade paper. In Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby owns a library full of uncut books, very elegant, mint-condition volumes that had obviously not been read. Students of literature have remarked on this tirelessly since the book was published—that Gatsby wanted to appear elegantly bookish although in fact he had no interest in reading. The alternative view is that Gatsby was a canny collector who didn’t want to spoil his books by taking a knife to them. That poses an interesting question: If one purchased Gatsby’s library, would one prefer the valuable, uncut, mint-condition books or the cut-open, well-read books with Gatsby’s greasy fingerprints all over the pages?

If I had the choice of buying an old, cut book as a reading copy or a newer, smooth-edged volume, I’d buy the cut book every time. I like the look of them and the smell of the old, dusty paper, which has a texture to it. Often they’re illustrated, which adds to their charm. The translation of Balzac’s The Thirteen that I own, published in 1899, has cut pages that are admirably ragged, as if the reader had haggled them apart with a rusty pruning saw. The book reads especially well. It was an Acres of Books bargain at 95 cents. I was a sucker for the central notion of the book: a secret society made up of thirteen rich and powerful men who controlled the workings of France in the early nineteenth century. In the years that followed my first reading of the book, I used The Thirteen as the working title for three different novels. In the back of my mind hovered the notion that if my anticipated plot failed, I could shoehorn a thirteen-member secret society into the book to jazz it up.

In another of my books the pages are cut until page 49, where the reader had apparently run out of patience and made a critical statement about the book simply by putting down the knife. My all-around favorite is a volume given by my great-aunt Esther to my uncle Paul when he was a boy—the 1926 Scribner edition of Kidnapped, illustrated by N. C. Wyeth. The book was passed down to my cousin Tom when he was a boy and then on to me. All the pages are cut except the final two, which are blank, something I could ascertain only by pulling them carefully away from each other and peering into the mysterious, eye-shaped void between. Why hadn’t Uncle Paul simply slit them apart, if only to finish the job? Why not make that final cut? I’m tempted to believe it was some variety of superstition, which prevents me from picking up a knife and cutting open the pages myself.

![]()

My favorite books are kept in my study, under the stairs in my house. I’m looking at them now. There’s a copy of Between Pacific Tides by Ed Ricketts and Jack Calvin, the 1962 edition revised by Joel Hedgpeth, whose last name I gave to two different characters in two different books. In my youth I kept aquariums and badly wanted to be a marine biologist and spend my life poking around in tide pools. Every creature that has ever crawled or walked or swum in a tide pool or lived in near-shore waters along the California coast is pictured in Between Pacific Tides. The foreword was written by John Steinbeck, my first “favorite writer” out of what has become scores of favorites, just as I have scores of favorite books, including Steinbeck’s Cannery Row. Ed Ricketts puts in an appearance as Doc, the owner of Western Biological Laboratories, the inspiration for which still stands in Monterey. The original building, where Ricketts worked and later lived, burned in a cannery fire in 1936, only a short time after the manuscript of Between Pacific Tides had fortuitously been sent to Stanford University for publication.

I first read Cannery Row when I was twelve or thirteen years old, and I can still remember how the place looked in the old days, before Monterey was modernized. I came close to buying the mummy of an “Indian princess” in a junk store on Cannery Row in 1972. The colorful, old cannery buildings were being knocked down and hauled away, and I was on a sentimental journey, looking for the ghosts of Doc and Ed Ricketts. They still haunted the place, although what passes for progress has very nearly obliterated them in the years since.

The thing about books, of course, is that the stories they contain are not ghosts but rather living things, which is a comfort for both the reader and the writer in me. There’s some small chance that fifty years from now someone will happen across a dusty copy of one of my own long-out-of-print books in their grandfather’s library and will read it on a whim. I’ll be a mere memory by then, and a fading memory at that, but the characters in my books will still be walking and talking, trying to make their way in the sometimes perilous world of the novel, which, all those years ago, was my world, at least as it existed in my imagination.

![]()

Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy rests on a set of shelves built into my study in what was once a window. I read the book for the second time in Ireland, sitting in front of a peat fire while Viki and our two traveling companions, Bill and Beth, were out driving around the Irish countryside. I stayed behind because I had eaten some dubious ground beef the night before, a bad idea from the point of view of my stomach, but what might be called a fortunate mistake. I can still smell the peat fire in my memory, and I fondly recall rereading particularly good paragraphs, with nothing to interrupt the solitude but my own occasional laughter and the bleating of goats cropping grass on the lawn.

There’s an old copy of The Return of Sherlock Holmes in that same window bookcase, published in 1905, one of the very first books I borrowed from my mother’s library. She was eager to aid and abet my reading habit, and when she saw that I was roaming the house looking for likely books, she decided to take my sister and me to the local library every other Tuesday afternoon. “Perhaps you’d like this book by Jules Verne,” she said to me on the first trip, and I came home with Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which turned out to be a gateway book. It opened my eyes and my mind to what a story could do—what it could teach you, where it could take you—and I was, as they say, hooked.

Later in life I tried to return the favor. When I was in college in the late 1960s, my mother was bedridden for a few weeks, and I supplied her with books out of my own library. She was particularly fond of Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet but not at all fond of his novel The Black Box, although she read it anyway. She was reading through Agatha Christie at the time, and so I gave her two or three Raymond Chandler novels, but she preferred the more cheerful streets of golden-age detective mysteries to the mean streets of Chandler’s mid-century Los Angeles. I could recall being quite happy when she’d given me Ivanhoe to read all those years earlier but not being half as happy with Mrs. Astor’s Horse. I remember all the books she gave me to read, whether I understood them or not, and I remember those sunny spring days years later when I’d get home from school and knock on her door to get a report on the day’s reading.

![]()

On the east wall of my study there are shelves built between the studs, and there sits the twenty-volume set of Scottish author and anthropologist James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough. I inherited the set from my bookseller pal Roy Squires after he died in 1988. Frazer’s interpretation of the nature of myth is another thing that has gone out of fashion, but his books contain thousands of strange entries of interest to a certain sort of writer: “The Sky Considered as a Heavenly Cow,” for instance, or, more in keeping with my own sensibilities,“The Sanctity of the Threshold.”

Squires’s friends, including me, divvied up a number of his books one evening, a sort of impromptu wake that included opening a bottle or two of Laphroaig. Roy had stockpiled a half dozen of the old clear-glass bottles of the Scotch preceding the infamous Laphroaig drought in the 1980s. It seems to me that the whiskey was subtly diminished when it reappeared in the world in its now-familiar green-glass bottle, but it’s equally likely that the world itself had diminished with Roy’s death. I’ve still got those books, though, and I think of Roy every time I pull one down from the shelf.

And now I’m nearly at the end of this story, this short look at one writer’s life in books. The long version, much like my library itself, isn’t to be countenanced, to use the old phrase. Opening that Gasoline Edition of the Belloc essays didn’t just kindle this meditation of mine but sparked a greater discovery: that virtually every book I’ve kept close at hand conjures up a story to accompany it.

Here’s one more for the road: Two linear feet away from The Golden Bough sits the thirteen-volume Works of John Ruskin, the Sidney Library Edition, illustrated throughout and published in a quarter-leather binding in the late 1800s. Viki gave me the set as a Christmas present sometime in the 1980s, when I was keen on reading all of Ruskin but ultimately failed to do so. I opened him up a month ago, however, and read a lecture in which he lambastes the people of Edinburgh for having too few Gothic windows in their buildings. I’m fond of the man’s arcane passions—the world badly needs arcane passions, which in today’s digital age some might argue would include a library—and I might tackle Ruskin again when I retire. But perhaps even more than their contents, I’m particularly fond of the books themselves, and the memory of the Christmas morning when I found them wrapped in a bow under the tree.

James P. Blaylock, one of the pioneers of the steampunk genre, is the author of more than twenty-five books, most recently the novel River’s Edge and the novella collection The Further Adventures of Langdon St. Ives, both published by Subterranean Press. Blaylock has taught literature and writing since 1976 and was a recent winner of the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program Teacher Recognition Award. He teaches writing at Chapman University in Orange, California.