The first Nicole Sealey poem I ever read opened with a simple declarative neutrality that hit me with riveting force—“I’ve been pregnant.” Between these first words and the title above them, “Medical History,” the white space opened, and my mind’s eye envisioned a consulting room, a procedure, a woman grieved or relieved or numbed. In five words, Sealey had conjured within me a bodily story. This power to invoke the visceral through seemingly straightforward language characterizes many poems in her debut collection, Ordinary Beast. In that book, published by HarperCollins in 2017, Sealey employs an array of forms, pivoting between play and gravity, to explore racial injustice, gender marginalization, love under mortality’s shadow, and the joy of an orchid. In her new volume, The Ferguson Report: An Erasure, published by Knopf in August, Sealey ventures into new thematic and formal territory. The book is a series of eight erasures, poems created by rubbing out words of a pre-existing text to reveal the writer’s lyrical response, which might echo, reconfigure, counter, or in other ways play off the original. An erasure may surface what is unspoken and who is not spoken for. For this new book, the poet uses as a source text the U.S. Department of Justice’s widely publicized 2015 investigation into police racism in Ferguson, Missouri, where teenager Michael Brown was murdered by police the year before. Sealey transfigures, echoes, and strips down the document. “My idea of erasure shifted from an archeological dig to a complete remodel of sorts,” she says. Sealey builds a dynamic tension between the report’s linear, data-based conclusions about racial injustice and her own lyrical flights that angle and dance against the faded background text to suggest that America’s most sobering racial truths may ultimately be as elusive as they are explicit.

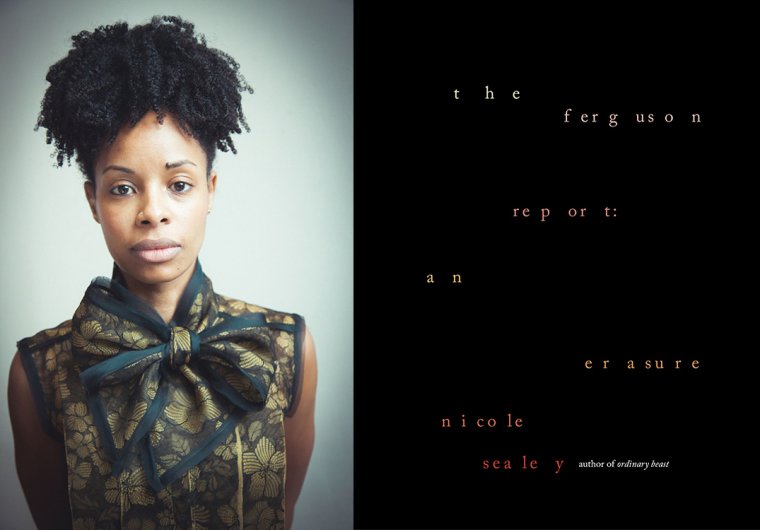

Nicole Sealey, author of The Ferguson Report: An Erasure. (Credit: Rachel Eliza Griffiths)

The poems comprise just over 600 words of the 84 pages she selects from the report. Individual pages contain as few as two words, becoming miniature declarations and fragmented pleas. The second page of the book, for example, reads like a poetic micro-deposition: “Particular—urge—at—gunpoint.”

The book deepens the intricate methods of working from borrowed sources that Sealey began in Ordinary Beast. In that volume, for example, she composed a 100-line cento that assembled opening lines by a vast array of modern poets: For the better part of a year, printed lines on paper scraps covered her dining room table and floor like a museum of leaves. Sealey spent the last six years conceptualizing and erasing The Ferguson Report.

Erasure often dissects a problematic text so that something at its root might be repaired. “There was something very satisfying about ‘reconsidering’ The Ferguson Report—striking through whole sections of it, as if undoing the harm that had been done,” Sealey says. With this volume, she has deepened an emerging American poetry subgenre of erasing legal documents to humanize their often marginalized subjects.

Sealey committed to a career in poetry at age thirty-two when she entered the MFA program at New York University, where she now teaches in the MFA Writers Workshop in Paris program. She is also a visiting professor at Boston University. She was born in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, and raised in Apopka, Florida. Ordinary Beast was a finalist for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award and the PEN Open Book Award. An excerpt from The Ferguson Report: An Erasure, was awarded the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem. Her other honors include a 2023–2024 Cullman Center Fellowship from the New York Public Library, a Rome Prize in Literature from the American Academy in Rome, a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University, the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize from the American Poetry Review, and fellowships from CantoMundo, Cave Canem, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. Her work has appeared in various publications and anthologies including the New Yorker, Poetry London, the New York Times, and The Best American Poetry (2018 and 2021).

During a summer e-mail conversation, Sealey and I discussed erasure as process and metaphor, how she spent six years turning a report on police racism into poetry, and the inspiration of wild animals.

Let’s start with the rich and literally layered idea of erasure. It’s a poetic form, a constructive (and subtractive) process, and also a cultural and political metaphor for truths, identities, and even bodies that are not permitted to freely exist. What has the idea of erasure meant to you in this fascinating project?

For The Ferguson Report: An Erasure I thought it important to editorialize, to introduce opinion, by way of the lyric and the image. The Justice Department’s The Ferguson Report is all facts, followed by recommendations based on those facts. By erasing the document, I could present its findings as well as what those findings incited in me. In so doing, my idea of erasure shifted from an archeological dig to a complete remodel of sorts. I ripped out the document’s drywall and essentially took it down to its studs. Because there was no impulse to reach after fact, as the facts had already been reached, I could remain in uncertainty, mystery, and doubt.

What drew you to The Ferguson Report as the source text?

I see myself, my family, and my friends in the victims cited in the report. And I welcomed the document’s conclusivity, its irrefutability. I didn’t read and reread the document with any project in mind. While thinking about how I might continue to engage with the report, I instinctively began by erasing it—not knowing what, if anything, would come from it. Six years later, here we are.

Can you describe your creative process of composing these brief poems interacting with the larger background text? I’m wondering about your physical as well as mental process. I remember a description you gave of your technique in assembling all the lines for “cento for the night I said ‘I love you,’” from Ordinary Beast. I’m imagining you reading document pages spread out on a dining table and circling words with a pen.

For the better part of 2016, while working on the cento, loose leaf with lines of poetry were strewn across my dining room table and floor. I’d survey the piles on the table and pace back-and-forth through the mess on the floor in search of the next line and the next. The erasure, on the other hand, required that I comb through The Ferguson Report, highlighting words of interest, page by page, as I was limited to the order in which words appear. The foraging for language was similar, but the worlds foraged were very different—the cento pulls from poems I love, while the erasure lifts language from a document difficult to digest. With this difficulty in mind, unlike background music intended to be an unobtrusive accompaniment, the report as backdrop is meant to be meddlesome.

Among the many images of body parts in this new book, hands particularly struck me. “Stop! Hands where I can see!” one line reads. I don’t want to literalize too much, but of course this suggests Michael Brown just before he was shot on the street in Ferguson, Missouri. And there are many others he stands in for. How are you thinking about the body and violations of the body?

The Barbican Centre is currently exhibiting the largest collection of multi-disciplinary work by American artist Carrie Mae Weems to date in the UK. The piece that concludes the show, It’s Over—A Diorama (2021), brings together photos of and offerings for victims of anti-Black police violence—candles, balloons, stuffed animals, and flowers on display together to recreate neighborhood memorials associated with such loss. I’d like to think that, like Weems’ work, The Ferguson Report: An Erasure memorializes the dead, while consoling the living. Necks, knees, bellies, backs, a tongue, an ear, skin, and flesh are featured. There’s no mistaking the subjects for anything other than human. The point is to make the body less theoretical and more physical. To make violations to the body less theoretical and more physical.

I’m fascinated by the prevalence of wild animals in your poetry. The collection opens with the line, “Horses, hundreds, neighing.” What’s happening among these horses, birds, deer, dogs, and beast, the creature that also appears in the title of your previous collection?

Animals often appear in my poems and collection titles, The Animal After Whom Other Animals Are Named and Ordinary Beast, for example. In high school and college, I studied for years to be a veterinarian. I’m no vet, obviously, but I’m still fascinated by animals and with anthropocentrism, the idea that humans are the superior beings. My resistance to this idea, I think, manifests itself in my work through the presence of animals. Horses neigh. A dog chokes itself with its own leash. Birds fly low and patternless. A deer flees. The day seems to growl. Given the context of the collection, these signs and scenes read ominous.

Can you talk about your approach to the one poem that interrogates meanings of the word force? I had a visceral reading experience, the constant repetition of that word like a body being hit repeatedly with blunt force.

There’s a stretch of The Ferguson Report that repeats the word “force” so often that the pages that follow feel somewhat incomplete. What was surprising is “pages thirty-five to thirty-nine” is pulled from the section of the report with less “force,” not more. It wasn’t until I’d read beyond the stretch that repeats “force” that the possibility of “pages thirty-five to thirty-nine” surfaced. A delayed reaction to the blunt force, so to speak. During the drafting process, the music that repetition elicited was oftentimes the only note holding movements together. I found that this repetition reiterates the incessance and insistence of anti-Black police violence, which has not and does not let up.

How did you work with the white space, which seems conceived as much geometrically as linearly in the way words and even individual letters are placed around the page?

I worked within the confines of the report. The letters, words, and phrases fell where they fell. When I happened upon them, I tried my best to pick them up and do right by them, lyrically. Musically. As a frame of reference for this collection, I think of pointillism, a painting technique in which small dots of color form larger images. Words in this work aren’t explicitly clear at first, like a written stutter. Figuratively stepping back from The Ferguson Report: An Erasure, so that greater space exists between reader and what is read, I think, allows for a more panoramic view.

Are you trying to stimulate any particular type of reading experience with the layouts? My own experience is that I’m being invited to actively share in constructing the poems, because I am literally building and puzzling out words and meanings from the letters separated across the white space. The way my eye moved to and fro in patterns felt kinetic, almost like dance. I waited until I’d read all the erasures to consult the “lifted,” lineated, versions appearing at the end of the book.

One reviewer compared reading the collection to using a Ouija board. The words appearing letter by letter. The Ouija board analogy feels apt—although it wasn’t my intention, it was certainly my experience. A former teacher and favorite poet, Yusef Komunyakaa, described the collection’s movements as “fleshy blips on the heart meter.” A dear friend painted the process as “equal parts language processing and visual processing.” You mentioned “puzzling out words.” All of these readings are right. Compared to the lifted poems, the erasure seems to move in slow motion, as readers piece together the words as well as the worlds of the poem. While the erasure determines the pace at which information is released, because it lacks punctuation, the reader determines when and where to place emphases. In contrast, because punctuation and enjambment are present, there’s a sense of direction with the lifted poems. There’s a clearer sense of the line, visually and rhythmically speaking. The lifted poems vis-a-vis the erasure provide an interesting kind of double interiority.

The book layout has a spare quality. The poems have no titles, just lower-case headings that reference The Ferguson Report page numbers. What are your intentions in using that approach?

I was hyperaware of this work’s central moving parts—The Ferguson Report and the erasure—which compete for the reader’s attention. This competition was expected and is welcomed, as neither report nor erasure are digressions, but rather relevant components that equally comprise the collection. The titlelessness, the lower-case headings, were tailored so as not to distract from the work’s main machinery.

I’m wondering, could erasure also suggest realities or possibilities that a poet or a poem’s speaker cannot access or articulate, are not allowed to, or that, for whatever reason, they choose not to express in language?

Erasure poetry is a reconsideration of an existing text. There was something very satisfying about “reconsidering” The Ferguson Report—striking through whole sections of it, as if undoing the harm that had been done. The process of prying lyric from a lyric-less document, however, was like pulling teeth, at best, and extracting water from stone, at worst. Still, I don’t think I would’ve been able to access the words for this work on my own, in any other verse form.

What’s one lasting impression or perhaps question you hope a reader might carry with them after reading your book?

At the close of “pages forty to forty-nine,” the speaker asks a rhetorical question. [See the erasure as it appears in the book.] I offer the question as well as what prompts it:

With the living, I am

familiar. A woman stretches

the truth to disappear it, throws

her voice to animate it. As when,

I imagine, the word was made

flesh. I’ve been trying to scrape

up what I remember:

1. 1,100 stems—long, headless;

2. a few bad apples;

3. “reports of a stolen pickup…”

You put down one color

Bearden thought and it calls

for an answer. What’s an answer

to black, I wonder?

From The Ferguson Report: An Erasure by Nicole Sealey. Copyright © 2023 by Nicole Sealey. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Erik Gleibermann is a social justice journalist, memoirist, and poet in San Francisco. He has written for the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian, Oprah Daily, Slate, the Georgia Review, Gulf Coast, the Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and World Literature Today, where he is contributing editor. His book-in-progress is “Jewfro American: An Interracial Memoir.”