In 1925 poet Edna St. Vincent Millay and her husband, Eugen Jan Boissevain, answered an advertisement for an abandoned blueberry farm for sale in Austerlitz, New York. They bought the property for $9,000 and named it Steepletop after the Steeplebush, a wild plant that studded the grounds with spiky pink blooms. Over the next twenty-five years, the farmhouse and surrounding seven-hundred-acre estate in the Berkshires near the Massachusetts border became Millay’s refuge, a haven where she could focus on her writing surrounded by forests, foothills, and wildlife.

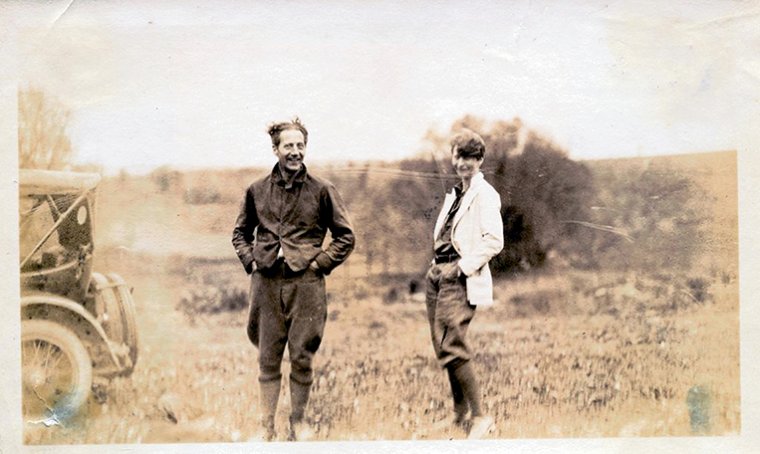

Edna St. Vincent Millay and her husband, Eugen Jan Boissevain, at Steepletop, in Austerlitz, New York, in 1925. (Credit: Millay Society)

Today the house is open to the public and is run by the Millay Society, a nonprofit trust dedicated to preserving the poet’s legacy. When Millay died in 1950 her sister Norma moved into the house, and after Norma’s death in 1986 the estate passed into ownership of the society. Since 2010 guests have been welcome to visit Steepletop and immerse themselves in Millay’s life by taking tours of the house and grounds. The estate, however, is in danger of closing after the current season, and the organization has launched a campaign to keep it open to the public.

According to the Millay Society, it costs $225,000 per year to run the property, which generates only $75,000 per year from visitors and donations, and the organization hasn’t been able to close the gap. With help in the form of $1 million in funding, Steepletop could remain open for at least three more years; $5 million to $6 million would ensure long-term financial health. (Steepletop is a separate entity from the Millay Colony, a writers and artists residency located just across the hill from the farmhouse, though residents are afforded access to the Steepletop grounds. The Millay Colony is not in danger of closing.)

Holly Peppe, Millay’s literary executor and friend of the family who once lived in the house with Norma, says the campaign has two ideal outcomes: to garner enough smaller donations from many sources to keep Steepletop running as an independent entity, or for a larger institution to partner with the Millay Society. Amherst College, for example, owns and operates the two properties that form the Emily Dickinson Museum, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Other nearby writers’ homes in New England and New York are largely kept open by a combination of grants, tour sales, rentals, programs, and individual donations. Within just a few hours’ drive from Steepletop, tourists can visit the Mount, Edith Wharton’s palatial estate in Lenox, Massachusetts; the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut; Arrowhead, Herman Melville’s home in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, with the famous view of whale-shaped Mount Greylock; and a number of homes formerly owned by Robert Frost.

But even among this abundance of literary estates, Millay’s stands out. “Steepletop goes beyond the home itself,” says Barbara Bair, curator of the Edna St. Vincent Millay collection at the Library of Congress. “It is special in that its surrounding grounds are still places of natural beauty—functional natural beauty—where people can still walk, picnic, read, observe a blossom, or listen to the birds, all with Millay’s spirit almost manifest around them.” Visitors can peek inside a small wooden shed where Millay used to write in the company of her German shepherd, Altair; the shed still contains two small desks and a typewriter. They can wander the gardens, fields, and wooded grounds where Millay and her husband threw extravagant parties—during which guests played tennis, drank at the well-stocked outdoor bar, and lounged in the spring-fed pool, where, legend has it, Millay decreed that guests could swim only au naturel. Visitors can also walk on the “poetry trail,” a path through the woods that leads from Steepletop to the burial site of Millay, her husband, and her sister, marked with placards of Millay’s sonnets along the way.

Bair calls the estate a “time capsule, a worm hole of consciousness that brings yesterday right into today.” Norma and the society preserved the house at Steepletop as though “Vincent”—as Millay was known to family and friends—had just stepped out for a drive. “Her gowns are hanging in the closet, shoes in the shoe rack, her feathered hats, her monogrammed purses with lipstick and blush,” Peppe says. Visitors to the house get a fuller picture of Millay, who, despite her reputation as a formalist “songbird poet,” was also a feminist who spoke out passionately for women’s rights and had multiple open relationships with women and men. In her wardrobe taffeta dresses hang next to her hunting jacket (“Millay had her own .22 [rifle],” notes Peppe), and Steepletop’s kitchen is still decorated as it was for a 1949 Ladies’ Home Journal article meant to show Millay’s “domestic” side, with blue walls and salmon Naugahyde cushions. According to Norma, her sister didn’t have much of a domestic side. Peppe says that when Norma first showed her the kitchen, Norma exploded: “For God’s sake, she wrote poetry here—her husband, Eugen, or one of the maids did the cooking!” she said.

Though Steepletop’s future is uncertain, Millay’s work is currently enjoying something of a renaissance. In 2016 Yale University Press published the first scholarly annotated edition of Millay’s poetry and plans to publish two new collections of the poet’s letters, diaries, and journals in 2021 and 2022. Peppe says that public understanding of Millay has also recently grown. A few decades ago Millay was acknowledged more for her celebrity—she had “rock-star fame,” says Peppe—than for her writing, but she is now being recognized as “much more of a modern poet than she was made out to be.” Millay’s sonnets inverted gender roles, giving the female speaker authority in a form traditionally reserved for expressions of male desire. “She wrote directly and openly about women’s sexuality, challenging romantic relationships in this world run by men,” Peppe says. “She was pigeonholed as a love poet, even in her lifetime. Now she’s finally being incorporated into the canon. Millay is an important historical figure and an important literary figure, and we’re just now finding out all about it.”

Adrienne Raphel is the author of the poetry collections What Was It For (Rescue Press, 2017) and But What Will We Do (Seattle Review, 2016). Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review Daily, Lana Turner, Prelude, and elsewhere.