In her electric first short story collection, Nobody Gets Out Alive, out today from Scribner, Leigh Newman gracefully walks the literary tightrope between intimacy and suspense. She gently draws us into the hushed turmoil that simmers just under the surface of her complex characters. But this book isn’t about resolving their struggles silently: Newman’s protagonists walk into the fire. It is impossible to look away as their actions shatter the delicate veneers that conceal their worst fears and disappointments. The 51-year-old Brooklyn mother of two, a former editor at Oprah.com and Catapult, is now editor in chief of Zibby Books. No stranger to the writing side of publishing, Newman is also the author of the acclaimed memoir Still Points North: One Alaskan Childhood, One Grown-Up World, One Long Journey Home (Dial Press, 2013), a finalist for a National Book Critics Award.

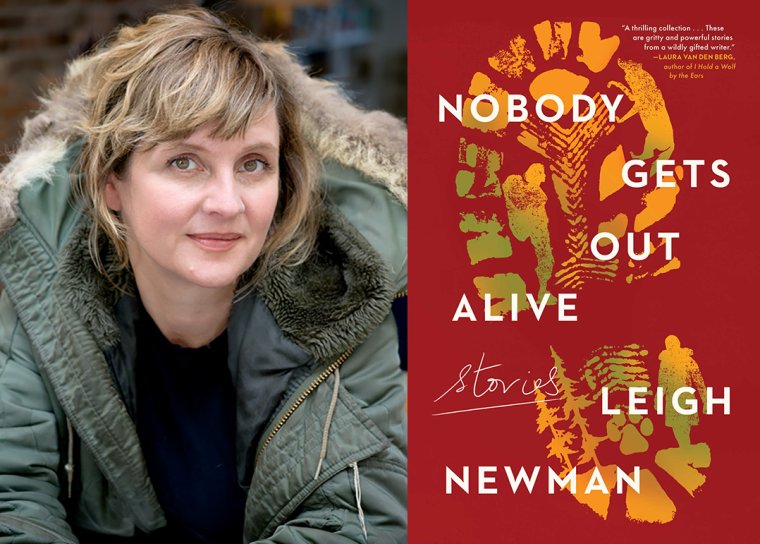

Leigh Newman, author of the story collection Nobody Gets Out Alive. (Credit: Nina Subin)

Alaska is in the foreground again in each of the interconnected narratives in this collection. Newman’s love for the breathtaking landscape is on glorious display as it sets the stage for the everyday lives she describes. “Stopping to call home while halfway up a shale-covered peak under a sky so blue you taste the color in your lungs pretty much ruins the moment,” she writes of a man on a sheep-hunting trip, while his wife contemplates drastic measures to deal with the anxiety of losing their marriage. Women hold center stage in every story: After being wife to five husbands a 67-year-old bankrupt widow makes a despairing attempt to sell her crumbling but unique home; a successful, pregnant businesswoman attempts to reconnect with her estranged family and community; a down-on-her luck psychic and escort tries to retain a shred of self-respect while being forced out of her workplace; a newly married investment banker flirts with an old friend at her own wedding party.

A sense of unease pervades the collection as Newman’s quietly desperate people attempt their high-wire acts. Yet these wild tales are also full of effortless humor and tenderness. Getting us inside the mind of a destitute single mother of two on the run from her abusive partner, Newman writes: “there is a vase of flowers in your heart that only people who like breaking things could see.” I felt I was in the hands of a masterful storyteller—a mead-flavored cocktail of Annie Proulx and Joy Williams. Both multitasking mothers of young children, we grabbed the chance to catch up over the phone and e-mail as a Northeastern winter gave way to spring.

Some early starred reviews call this collection as “big hearted” and describe the Alaskan women in it “hardscrabble” and “larger than life.” But a few of the stories are told by men, aren’t they?

I love the word hardscrabble. It’s just a pleasure to say. Like rollicking or chicken. And certainly, most of the star characters in this collection are women—poor women, rich women, women struggling with abusive partners, poverty, addiction, alcoholism, queerness, lack of love. That was the point of writing the book for me, to tell a very different kind of frontier story. When I was in college, there were a lot of stories about tough, nomadic guys in Montana guzzling beer and cavorting with elk. I liked those stories. I learned from them. But they seemed to leave out all the mothers, all the kids, all the bookkeepers and dentists and housewives, the ordinary women living on the edge of the wilderness, shopping at JCPenney as well as hunting and fishing. My hope is that I’ve been able to show the richness and range among Alaskans as I intended. As for the stories with a male narrator, there are really only three and all of them are looking at a powerful, perplexing woman in their lives—a woman who has stumped them in some way or refused to go along with the status quo. For me, that’s just reality. If we’re looking at women, we need to look at how men look at women, how girls look at women. And boys. Otherwise, it’s a lopsided picture. There are 111 men for every 100 women in Alaska—how that ratio plays out is…well, the stuff of stories.

In the title story “Nobody Gets Out Alive,” Carter is insecure about his relationship with his new wife, Katrina. But he is also seduced by her hunger for “pointless personal accomplishment” as you say in the story. What made you choose it as the title story?

“Nobody Gets Out Alive” was the first thing I had ever written that came together as what I think of as a fully fleshed-out story where I wasn’t grasping for an ending or panicked over what to include or leave out. I wrote it a decade out of grad school—I spent my years in grad school stewing over poorly executed stories, none of which really landed. I knew I had never mastered the form and I revered those who had—Edna O Brien, Toni Cade Bambara, Charles D’Ambrosio, Mia Alvarez, Karen Russell, Flannery O’Conner, Edward P. Jones—and I was a determined to do it, even if the book took me forever, which translated into eight years of my life. All the characters in that story ended up with their own stories or ended up popping up all over the collection like desperate, young mushrooms. In some ways it was the mother story for me as a writer. It’s a story that beget a whole book, a whole pursuit of an art form and all its intricacy. But the line “Nobody gets out alive” came from my dad. “Nobody gets out alive” was what my grandfather said to him when he told him he was dying of cancer. My dad was 17. His dad was 45. It’s a brutal thing to say to a kid, but it’s adult and true and comforting in its lack of resolution. We’re all headed to the same place. And it captured everything I was trying to get to, emotionally—all the love, all the horror, all the grief.

Eight years should be considered short in parent-writer years; I am a single mother and struggle to find time to write. What were those eight years like for you?

My life was in freefall during the writing of the book. Two years of it, I was a single mother to two kids, with a full-time job and a part-time job on top of it. I was depressed, exhausted and ran outside every night to this little shed we had in the backyard—from which I could see my kids avidly playing video games in my bedroom, on my bed, their faces contorted with joy and addiction in the blue of our crappy TV—while I typed away until 2:00 in the morning. Any sane person would write a novel or a screenplay, go for the big money, write one continuous story instead of having to begin a new world with all new characters every twenty pages. It had been so long since my first book; I was pretty convinced nobody even remembered I was a writer, much less cared. But I guess that takes us back to the title story. Nobody does get out alive. I had to make a diamond in the backyard—out of bravado and manure. I have very little advice or wisdom about the situation. But struggle is conflict. And conflict is story.

The narratives here seem intertwined without being continuous. Katrina is a child and not the main character in the story “High Jinks” but is grown up in “Nobody Gets Out Alive.” Janice is Neil’s wife in the title story and also the daughter in “Alcan, an Oral History.” I felt like I was hearing stories about a community.

Thank you, that’s just what I was trying to do. These are all stories of people living around Diamond Lake—a lake I invented that is not dissimilar from other suburban floatplane lakes in Anchorage, where people have a nice house with two-car garage but also a Cessna 185 floatplane tied to the dock out back so they can fly out to hunt and fish and climb and float rivers. It’s specific kind of community: people who made it due their business smarts and ability not to fit in anywhere else, people who are actively in pursuit of something wild and out of hand, people who possess truly miraculous level competency about the little crap that will kill you—crap like rain covers and snow in your shotgun barrel. Naturally, they are friends, they are neighbors, they are lovers. It’s small world, bound by a shoreline. This book is me sitting around a campfire with my readers telling them stories about people I know and love.

Your love for place and your characters comes through in every story. But you’re also not shy of bringing up real problems, such as the staggering sexual assault statistics in the state in “Valley of the Moon.”

Only two of the nine female friends I grew up with in Alaska escaped rape, molestation, or domestic abuse. Nothing I describe in my stories took much imagination. The last time I went to a bar—not even a real bar, a restaurant I love with a bar—my soft-spoken female friend was told to shut her face by an enormous drunk guy in a trucker hat. He was eating eighty bucks’ worth of king crab legs and spewed little bits of his crab meat in our face. I think my friend was talking about poetry. He didn’t like it. Nobody stood up for us or asked him to leave. I almost told him where to go—but I’m not that stupid. I like my nose. We sat there—strong, independent women rendered silent. For that reason alone, I wrote this book.

Your characters are flawed and complex. Danielle in “Alcan, an Oral History” abandons her closest friend Maggie at night in a scary, unfamiliar place. Meryl cheats on her husband in “Slide and Glide.” Were some harder to love than others?

Not at all. I love everybody who is not perfect. Which is everybody.

“Our Family Fortune-Teller” is an incredible story in which you’ve portrayed an overlooked establishment—an escort business with a full-time psychic. What drew you to writing about it?

One of the storefronts in downtown Anchorage used to have a neon sign: “Card Reader” in pink neon. The story came from that sign. Most of my work, as you can tell, is realistic. But here I wanted to attempt one with a bit of a magical realism feel, as a nod to the uncanny. It was craft challenge for myself.

As an editor, do you think you see enough stories written by cisgender men that show the male perspective with vulnerability and nuance? I feel you’ve done that with your male protagonists in your collection.

At Catapult I used to end up acquiring only women and gay men authors. I didn’t plan it that way. There was a time in the early 2000s when someone had told me that no one will be interested in a story written from a woman’s perspective. So I used to aspire to being a writer like men who wrote with this cold remove. Those stories are obviously out there and have their place. These days though, I do think men like Charles D’Ambrosio are writing more complicated, vulnerable characters.

What attracted you to the short story as a form?

It is ephemeral and intense. And unforgettable.

Puloma Mukherjee is an immigrant writer and mother based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Guernica and the Los Angeles Review of Books, and in an anthology of short stories. She is currently working on her first novel.