This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Aldo Amparán, whose poetry collection, Brother Sleep, is out today from Alice James Books. In this intimate debut, Amparán explores coming of age through a series of losses: the death of a brother, grandfather, and the disguises worn to meet the world before becoming one’s authentic self. Across lyrics that blend narrative and formal experimentation, Brother Sleep interrogates identity as formed within the family unit, larger social systems, and the spiritual realm, in which “the universe can fit inside an urn | or a casket.” The poems carry readers through various real and psychological spaces: from the bed the speaker once shared with his brother to schools prowled by homophobic bullies to the inner landscapes of insomnia and grief. Part elegy, part queer-awakening story that plays out on the U.S.–Mexico border, the book imagines bereavement as a force interwoven with the body’s living demands: “Some nights I want a mouth to kiss,” Amparán writes. Jericho Brown calls Brother Sleep, winner of the 2020 Alice James Book Award, “a wild ride.... Each poem is an example of a poet who’s mastered his craft well enough to retrace steps back to the place where family, nationhood, and exile meet.” Aldo Amparán is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and CantoMundo. Their work appears in or is forthcoming from AGNI, Best New Poets, Black Warrior Review, Kenyon Review Online, and elsewhere. They hold an MFA in creative writing from the University of Texas in El Paso, where they teach.

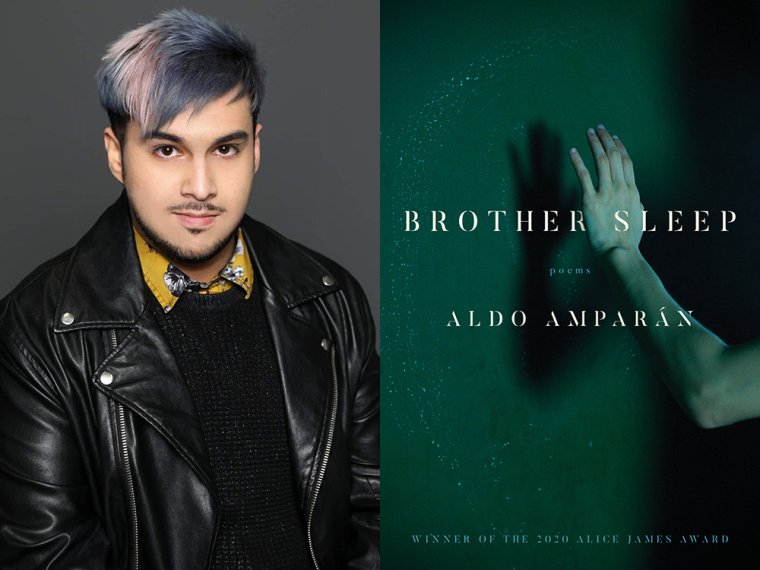

Aldo Amparán, author of Brother Sleep. (Credit: Alice James Books)

1. How long did it take you to write Brother Sleep?

The earliest poem I wrote that made it into the book was “Primer for a View of the Sea.” About eight years ago, as an undergraduate, I wrote its original draft, forgot about it, and rediscovered it as I was working on my MFA thesis. Most of the poems in the book were created during my last year in the program. It took me another three years after graduation to edit the manuscript to bring it to its current state.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Raised in an environment that viewed vulnerability as weakness, I still find it challenging to be vulnerable despite being deeply emotional. Yet I continue to write about my most vulnerable moments. With Brother Sleep I remembered a specific period of my life as I navigated high school. This is when I experienced the loss of my grandfather and a very close friend while struggling to come out as gay.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I usually write at home or at work in early mornings or late nights. There’s something about afternoons that is so distracting. I try to write every day, even if what I write is awful and not meant for anyone to read.

4. What are you reading right now?

I attempted the Sealey Challenge—the poet Nicole Sealey’s project of reading one poetry book a day during the month of August—so I’ve read many wonderful poetry collections recently: Shangyang Fang’s Burying the Mountain, Katie Marya’s Sugar Work, and Brian Tierney’s Rise and Float were some of the standouts. I’m also reading Ottessa Moshfegh’s latest novel, Lapvona.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I found organizing the poems to be the most challenging part of the process. Although I loved it, I was constantly doubting myself. Because many individual poems refuse closure, I wanted the progression of the manuscript to arc toward some kind of acceptance.

6. How did you arrive at the title Brother Sleep for this collection?

When I started writing this collection, I used the voice of Sleep, Death’s brother in Greek mythology, to help me express myself openly about grief, family, and desire. The title stuck. It has a quietness to it, a calm that contrasts with the grief and violence that the speakers in the book endure or are witnesses to.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Brother Sleep?

Although I expected writing about this period to be emotionally draining, I was pleasantly surprised by how therapeutic it was. It helped me understand many feelings I had avoided. Perhaps ironically, this book helped me find closure.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Brother Sleep, what would you say?

For a long time I refused to let go of my poems. I refused to submit them to literary journals and only started doing so after graduating with my MFA. I didn’t feel my work was good enough. I’d tell my past self to trust my work. To dare.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

In the book there’s a sequence of poems titled “Glossary for What You Left Unsaid,” which I wrote based on the definition of specific words. For words in English, I researched their definition in the Oxford English Dictionary. For words in Spanish I used the Dictionary for the Spanish Language from the Real Academia Española.

“Interrogation of the Sodomite,” “42,” and “Black Palace Blues” all speak about a specific event in Mexico’s history regarding the persecution of gay men. The poems, especially “Black Palace Blues,” went through considerable editing because some of the sources I used were contradictory.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

In a lecture Jericho Brown gave at the University of Texas in El Paso when I was a graduate student, he emphasized the importance of patience. This was such crucial advice to me after I began publishing my work.