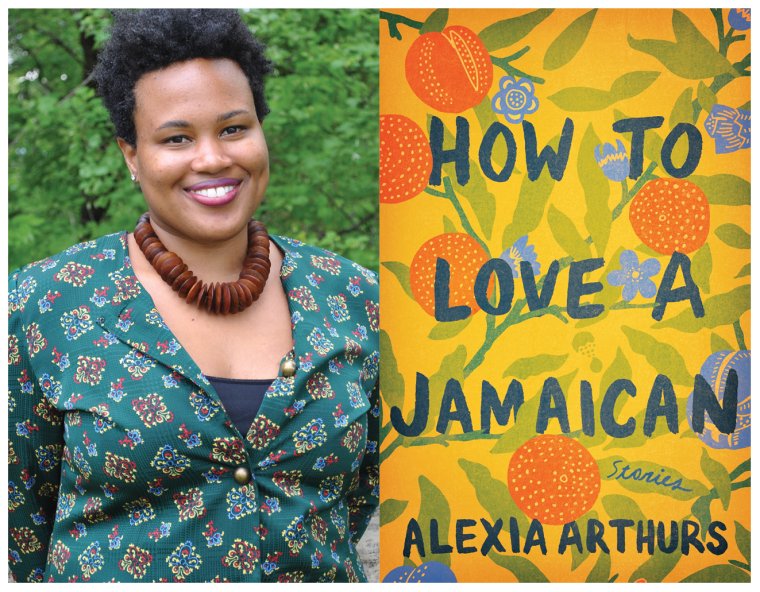

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Alexia Arthurs, whose debut story collection, How to Love a Jamaican, is out today from Ballantine Books. Drawing on Arthurs’s own experiences growing up in Jamaica and moving with her family to Brooklyn, New York, at age twelve, the stories in this collection explore issues of race, class, gender, and family, and feature a cast of complex and richly drawn characters, from Jamaican immigrants in America to their families back home, from tight-knit island communities to the streets of New York City and small Midwestern college towns. Arthurs is a graduate of Hunter College in New York City and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and her stories have been published in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Vice, and the Paris Review, which awarded her the Plimpton Prize in 2017.

Alexia Arthurs, author of How to Love a Jamaican. (Credit: Kaylia Duncan)

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I love lattes and coffee shop ambiance, but whenever I try to write in public, I regret it. Everything and everyone is too loud. I need to be in the privacy and quiet of my home, at my desk with a cup of tea. I drink lots of tea when I write. My magic hours are between 12 AM and 2 AM or until I absolutely can’t keep my eyes open anymore. If I’m working on something, I try to write as often as I can—every day, every other day, whenever I can. I can go weeks without writing if the material isn’t pressing. I can’t decide if my writing is better when I feel inspired, or if it’s the process that feels more pleasant.

2. How long did it take you to write How to Love a Jamaican?

I wrote the first story, “Slack,” during my first year of graduate school—this was late 2012 or early 2013. I finished the last story during the winter of 2017.

3. What has been the most surprising thing about the publication process?

Often writers talk about writing in an individualized way, our dreams and failures, but on the other end, it feels like a community project—it’s for the culture, for my culture. How to Love a Jamaican feels bigger than me. A surprising and beautiful realization. I’ve gotten messages from people who tell me that they were waiting on a book like mine.

4. Where did you first get published?

I published a short story called “Lobster Hand” in Small Axe.

5. What are you reading right now?

All the Names They Used for God by Anjali Sachdeva. It’s incredible. This is such a good year for short story collections.

6. If you were stuck on a desert island, which book would you want with you?

The Bible I’ve had since I was a teenager. It’s marked-up and worn, and it is one of the most precious things I own. I’m not religious anymore, or I’m still trying to figure out my relationship with religion, but my family is, and my father was a minister when I was growing up, so Biblical stories still hold personal relevance for me.

7. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

Whenever I’m asked this question (if I’m asked this question again—I was asked this question last week) I’m going to name short story collections I love. We need to get more people reading story collections! I really admire You Are Having a Good Time by Amie Barrodale and Are You Here For What I’m Here For? by Brian Booker.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

All of my feelings and daydreaming. It’s hard sometimes to sit still and trust the process. The other challenge is the pain of recognizing myself in my writing because my stories come from such a personal place. I don’t always feel like looking in a mirror.

9. What trait do you most value in your editor?

Kindness. Intelligence is nice, but kindness is lovelier. Andra Miller has both. I respect her as a person and as a thinker.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I took photographs in high school. There was a dark room, which now feels like a small miracle in a public high school in Brooklyn, New York. When I was graduating, my photography teacher, Mr. Solo, gave me a little book—The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers by Henri Cartier-Bresson. He taped one of my photographs in one of the blank pages and wrote a note saying that he hoped I would stay involved in art-making wherever life took me. Not really advice, but encouragement, which for me is the same thing. I still have that book. What he did was one of the most generous things a teacher or anyone has ever done for me.