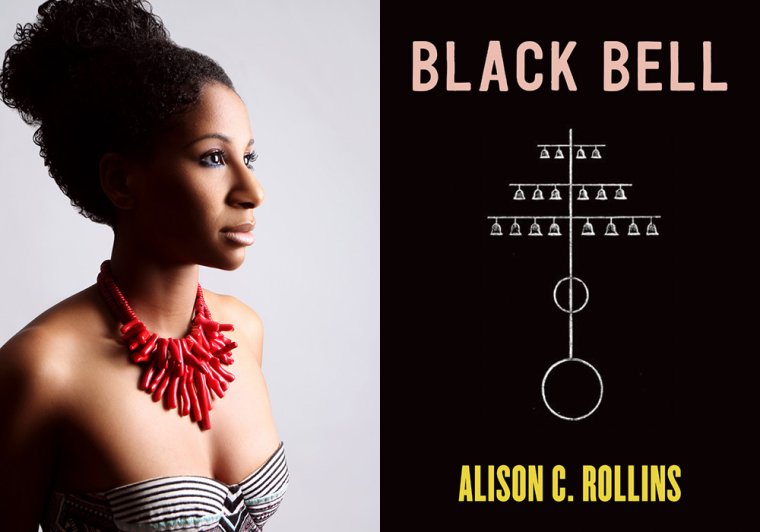

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Alison C. Rollins, whose second poetry collection, Black Bell, is out now from Copper Canyon Press. A dynamic collection filled with images, diagrams, and verse experiments ranging from concrete poetry to a poem in the form of a Turing test, Black Bell offers a poetics of Black survival and liberation. The book’s title alludes to a device worn by enslaved people in the nineteenth century as a form of constraint and punishment. Rollins refashions the bell device literally and figuratively in this collection, with poems contemplating the material, cosmic, and spiritual dimensions of bells while incorporating their sound into the verse itself: Several poems begin with notes that they be performed with the accompaniment of bells. Rollins herself incorporates musical performance into many of her readings, including by wearing a device reminiscent of the one alluded to in the book’s title, an archival image for which can be found in the collection. Black Bell otherwise pays homage to Black historical figures, including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Langston Hughes, Harriet Jacobs, Phillis Wheatley, and others whose creative life force infuses the collection. Publishers Weekly praises Black Bell, calling it “an unflinching and incisive compilation.” Alison C. Rollins is the author of Library of Small Catastrophes (Copper Canyon Press, 2019). A recipient of the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, a Harvard Radcliffe Institute Fellowship, and a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, Rollins holds an MFA from Brown University and is an assistant professor of English at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Alison C. Rollins, author of Black Bell.

1. How long did it take you to write Black Bell?

I consider book publication to be a lifetime in the making, so my answer would be my current age of thirty-six years. This book’s discussion of time and space operates in some ways like a time capsule for me across the past, present, and future, so the concept of “how long” is beyond realistic measure. Black Bell is my second poetry collection, so in many ways it builds and expands on my first book, Library of Small Catastrophes, which was published five years ago, in 2019.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

During the latter stages of writing this book, I battled feeling quite lonely, so that was a struggle. But I know that in my making I am never truly alone. Writing a book that is steeped in history and the archive but is also fresh and queer was a fun but particular challenge in terms of asking readers to trust that the narrative strands of the book pleasurably thread together, even when they feel particularly disparate or far reaching. I was pregnant while I did the final edits of the book, so watching my body house a child while preparing to usher a new book into the world was no small task!

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write most days, often using the Notes app on my phone or in little locket journals using mechanical pencils. I don’t hold myself to a rigid writing schedule but instead listen to my mind, body, and heart and write accordingly. I view self-care and being in community with those I love to be forms of writing that are not connected to labor and capital. It is just as important for me to rest as it is to produce. Now, as a mom, I have a little baby to care for, so realistically I write whenever I can get a moment to myself!

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes and am currently reading Toni Morrison’s Paradise, Camille Dungy’s Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, and Airea D. Matthews’s Bread and Circus.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I knew I wanted to have four sections to represent a quartet and with the understanding, in thinking about the word stanza translating from the Italian to room, that a room has at least four corners. Music figures prominently in the collection, and I knew that I would have one section regarding the seasons open with a Stevie Wonder quote and another section with a Sun Ra quote. One of the epigraphs of the book is taken from Moses Roper’s 1837 A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, From American Slavery, in which he shares the story of a young, enslaved girl trying to escape; she is wearing iron horns and bells, a contraption Roper says the owners of enslaved people made them wear as a form of punishment. The book’s four sections are in tribute to her fugitivity.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

The MFA is a terminal degree that has a particular function, such as serving as the qualification for an academic job. Obtaining a job qualification and being a writer are arguably two different things. I got an MFA after already earning a master’s in library and information science and working for years as a librarian. I recommend writers do whatever they need to hone their craft while centering joy, play, love, liberation, and rest.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Black Bell?

I found myself surprised that poetry, as a genre, would uniquely afford me a type of liberatory play on the page and in my lived experience as a poet. I surprised myself by experimenting more with language as malleable sound that can be powerfully manipulated in terms of both speech and silence. I’m thinking a lot about voice and percussion instruments with this collection. I also am thinking more thoughtfully and critically about the act of giving a public reading as a work of performance art.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Black Bell, what would you say?

I would reassure the earlier me by letting her know that she is going to create something outside the bounds of what she has ever read before or thought was even possible. I would tell her to follow her gut, stay the course, be strong, and keep dreaming, imagining, pushing!

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I am a researcher and librarian at heart, so I did a lot of research in physical archives as well as in online databases for this book. “Freedom on the Move” (a database of fugitives from North American slavery), the New York Public Library, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture are just a few of the sources I drew from for the collection.

For this collection I learned the trade of arc-welding to be able to practice metalwork to make a “sound suit” to wear while reading, or rather performing, poems from the book. I delved further into performance art and sonic practices for this book, viewing the poetry as a musician or composer would a musical score. Additionally, I developed a small but substantial collection of bells to use in connection with the work to create a more percussive live experience when I give public readings.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

It would probably be Toni Morrison’s prompt, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it,” coupled with Thelonious Monk’s belief: “A genius is the one most like himself.”