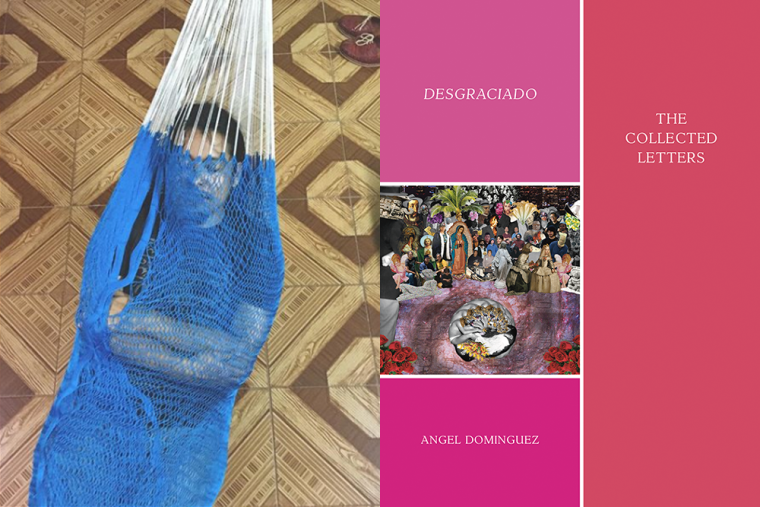

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Angel Dominguez, whose epistolary poetry collection, Desgraciado (the collected letters), is out today from Nightboat Books. In the letters that comprise Desgraciado, Dominguez, who is of Yucatec Maya descent, speaks back to Diego de Landa, the sixteenth-century colonizer who nearly eradicated the written Maya language. It is not an easy task to conjure the dead: “It’s always this approximation that lacks a temperament,” writes Dominguez. “You lack a temperature. You lack a sense of woe. Sometimes, I fold you up into an idea. Sometimes, I let myself eat what’s left of you.” But the poet persists, and with each letter and repetition of “Dear Diego,” they refuse to let their voice go unrecognized. They challenge the dead man, but they also find their own “organs in the rubble.” They offer evidence of themselves and all the nuances of the legacy of colonialism. “Angelito’s letters to the pinche colonizer are portals, cenotes on the page that open up a profundo space in this Western void that allows our brown skin movement and luz and gives us answers to preguntas we have not been allowed to ask,” writes Josiah Luis Alderete. Angel Dominguez was born in Hollywood and raised in Van Nuys, California, by their immigrant family. They’re the author of ROSESUNWATER (Operating System, 2021) and Black Lavender Milk (Timeless Infinite Light, 2015). Angel earned a BA from the University of California in Santa Cruz and an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University.

Angel Dominguez, author of Desgraciado (the collected letters). (Credit: Kit Schluter)

1. How long did it take you to write Desgraciado?

This project first started back in the summer of 2014 during the fabled Summer Writing Program hosted by the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. I was fortunate enough to be taking a workshop with Farid Matuk and Susan Briante. That class opened me up to a lot of things that continue to open me and my work in unexpected ways. Farid gave us a prompt that was something like, “Write a love letter to your worst enemy,” and I could not think of a worse enemy than Diego de Landa. And so that first letter was written then and there: June 6, 2014, in Boulder, Colorado. The last letters/pieces, including the first line of the book, were written when we were down to the wire with proofs and edits in fall 2021. So all things told this book took seven years and some change to get to where it is now. Between the first and the last letters lives a whole other lifetime of the project existing as a chapbook with Econo Textual Objects, and there were countless fragments, files, and even whole notebooks lost to being alive. That’s what makes this book the collected letters.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I think among the most challenging things about writing this book was reckoning with what it means to be honest, not only as a poet and writer, but what it means to be honest as a human being living in the world. Determining how to best communicate the vast interconnected experiences of the interior. How do you reconcile hundreds of years of atrocities? How do you reconcile the constant colonization or neocolonization of the mind? How do you navigate a life in opposition to and in spite of systemic racism, with poetry? I don’t know. I think in all honesty the most challenging thing about writing this book was realizing that I was fighting a fight I could not win with poetry. Decolonization is a verb. An ongoing process and not an imaginary destination.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I used to think I needed idealistic conditions—the right space, pen, notebook, and so on—in order to write, and it was really in the writing of this book that I realized writing happens all the time, it’s just a matter of capturing the thing. I write anywhere/anywhen I can. I once took this practicum with Harryette Mullen over a snowy weekend in Colorado. She said, “Give yourself permission to write,” and that’s exactly what I’ve been trying to do from that day on. Writing wherever the writing occurs. I’m always listening to wherever poetry/writing comes from, trying to catch whatever rogue language it might speak/sing or otherwise bring through to me. I think it also needs to be said that time spent thinking is time spent writing. Thinking is writing. In that way I’m always writing—it’s all part of the “project” whatever that might be in the moment of thought. It’s all attending to the cultivation of one’s own craft. That all being said, I’ll write wherever the writing arrives, whether at a table, desk, or on the road. But I recommend using a voice memo or pulling over; I do not recommend scribbling the thing while driving. I’ll write with whatever’s at hand, be it a notes app, notebook, receipt. The importance lies in capturing the immediacy of the thing. These days the writing has slowed down a bit, mutated into essays—like “A Backyard Funeral Afterparty para Latinidad” published by Open Space SFMOMA last fall—and little and not so little poems, stories, and dreams of other projects.

4. What are you reading right now?

Recently I’ve been reading Blood on the Fog by Tongo Eisen-Martin, The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century by Gerald Horne, a book on the Caste War of the Yucatán by Nelson A. Reed, and Kit Schluter’s new translation of Rafael Bernal’s ecofiction His Name Was Death. I’m also really excited about Raquel Salas Rivera’s new book, antes que isla es volcán / before island is volcano, and Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta’s La Movida.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are far too many to name all at once. The names that immediately come to mind are: Jzl Jmz (fka Jayy Dodd), Francisco X. Alarcón, Joey De Jesus, Wanda Coleman, and one name that sticks out in my mind is Ronaldo V. Wilson, who is criminally under-celebrated/recognized for his contributions to poetry, writing, and art making at large. His two most recent works, Carmelina: Figures and Virgil Kills, are truly stunning and I hope they bring Ronaldo the flowers he deserves.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Capitalism! Which also happens to be the biggest impediment to everyone’s life. The systems and structures of power that prop up capitalism value these imaginary notions of capital and currency above human life, and that alone is impediment enough. The “Dow Jones” doesn’t have a pulse. People do. It’s like they think we’ll forget that if only we have enough distractions.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

I don’t have an agent at this time, so I’ll answer for what I value most in an editor: honesty, clear communication, and trust. Those three things all feel like the same thing to me, and I’ve been very fortunate to work with a number of absolutely stunning editors whose clarity and questions have helped my work grow in ways I wouldn’t have been able to make it grow myself. It has to be said: The first real editor of this work was Raquel Gutiérrez, whose editorial eye and kinship pushed Desgraciado to be a polished Obsidian Mirror and become a chapbook. In working on the final manuscript with Nightboat, I got to work with Andrea Abi-Karam, who pushed the book further toward becoming a reality, asking the tough questions and bringing in the importance of the overall energetic wavelength of the book, its shape, and flow.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

They had to take it away from me! In all seriousness, it was when I was on a Zoom call with Kit Schluter, who designed the book and worked tirelessly with me and the Nightboat team to bring together the cover you see today. I’d worked forever on this collage that appears on the cover, and when Kit sent over the proofs of the current cover, I just knew. This is it. This is the book.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

There are a few names that immediately come to mind, each with their own reasons for being a most trusted reader. My partner, Hannah Kezema, is a brilliant artist-writer and an obsidian-sharp editor—someone whose eye and ear I trust to tell me if something is actually garbage or worth salvaging. I also keep a close circle of artist-writer friends with whom I’ll check in about new work or work that’s going to print. I’m forever indebted to my Kin: Daniel Talamantes, Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta, Raquel Salas Rivera—who wrote the brilliant foreword for Desgraciado—Erick Sáenz, Domingo Canizales III, and MJ Malpiedi for always being so generous with their time and energy when it comes to reading/reviewing my work. I would be nothing without my Kin.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It feels really cheesy to say this, but my high school English teacher Mr. Peter Chase once told me, “Write what you know,” and I’ve been trying to ever since.