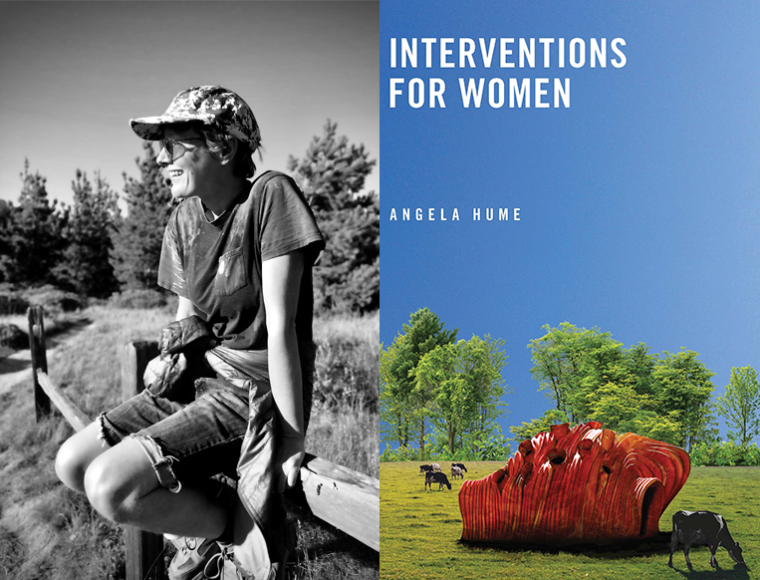

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Angela Hume, whose second poetry collection, Interventions for Women, will be published on October 1 by Omnidawn. In the long poems that make up Interventions for Women, Hume considers both the individual and communal consequences of the crises of the contemporary era. For instance, in the title poem, which tackles the violence of the industrial food system, she sets statistics on food inequality and environmental degradation alongside personal narratives that reveal how the system affects feminized people. And with the collection as a whole, she tracks how the various crises—climate change, white supremacy, sexual violence—interlock with one other. Always operating at multiple levels, Interventions for Women documents the world and its evils with unusual clarity and begins the work of imagining a more just future. “This poetry is indeed a powerful counter to our death- and profit-driven culture, which harnesses our bodily and psychic desires with food and commodities and societal structures that do us profound damage and cannot nourish us,” writes Brian Teare. “We have never needed this music more.” Angela Hume is the author of a previous poetry collection, Middle Time. Her chapbooks include Meat Habitats, Melos, The Middle, and Second Story of Your Body. With Gillian Osborne, she coedited Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field.

Angela Hume, author of Interventions for Women.

1. How long did it take you to write Interventions for Women?

I wrote Interventions for Women during the Trump years. The book is made up of long and longish poems. I started writing the first, “drowning effects,” in summer 2016 as the Big Sur coast, Los Padres National Forest, and Ventana Wilderness burned. In the poem, I wanted to write about environmental grief and how it feels connected to queer life for me. I was thinking about how hard it is for humans when we don’t get what we want. And how in our time of massive ecological change, disappointment—that crushed feeling that I think a lot of queer people understand in a deep way—is also a kind of environmental affect or feeling. I realized that my feelings of shame around what the dominant heterocentric culture would call “failure”—my “failure” to partner, accumulate wealth, and have children, for example—are related to a feeling I experience when I witness a degraded environment still in the early stages of recovery. So I started to read about restoration ecology. How it doesn’t typically happen in a linear way. Instead, there can be a lot of starts and stops. And slow, discontinuous, or swervy doesn’t mean it’s not working. When we’re too shortsighted and normative, we mistake unexpected variables and deviations for negatives. But they’re not negative necessarily.

I started reading Audre Lorde on restoration as well. In her writings post Hurricane Hugo, she explores the relationship between “man-made” disasters, restoration, and queer love. The truths she tells in her journal fundamentally informed the ways I went on to think about violence and survival.

I wrote “drowning effects” mostly before the fires of recent years. The devastating Camp Fire. The August Complex, SCU Lightning Complex, Mendocino Complex megafires. Most recently, Dixie. 2016 was a different time. I worked slowly and continuously on Interventions into the fall of 2020, during the August Complex, which burned more than a million acres.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Trying to track American fascism in its unfolding.

Also, I was trying to write about something personal that’s political. I wanted to write about my disordered childhood relationship to food—its relationship to my experience of childhood and young adult gender and sexual violence. And about how I now understand these things as small but not insignificant entries into the grand historical register of Christian settler white supremacy. One thing I wanted to think about is how working- and middle-class white girls, women, and feminized people are conscripted by the white supremacist capitalist state to perpetrate violence against working-class and poor girls, women, and feminized people. As we speak, power is quietly but aggressively laboring to dismantle poor people’s access to abortion and reproductive justice—TX S.B. 8 being the egregious recent example. A white woman’s vote could help overturn Roe v. Wade, and soon; the Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case that challenges Roe directly on December 1.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write poetry when I’m in transit or transition. Between cities. Relationships. Moments of political eruption. Selves. For months I’ll work obsessively on poetry every day. Then I’ll go months without writing any poetry at all. My work on nonfiction is more methodical: slow and steady.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading about abortion. All about abortion. Care. Law. Defense. Mary Ziegler on abortion law. Jenny Brown’s Without Apology. David S. Cohen and Carole Joffee’s Obstacle Course. Michelle Murphy’s The Economization of Life. It’s research for a nonfiction book I’m writing about radical abortion defense and reproductive freedom/justice movements in the Bay Area. A lot of it is about gynecological and abortion “self-help”—feminist and anarchist projects of the seventies, eighties, nineties, and beyond that are instructive for today. One thread is about an Oakland clinic that managed to keep its doors open for nearly four decades. I’ve spent years in archives. Oftentimes the archives are people’s bedroom closets. Through my research—reading extensively into people’s personal collections and conducting oral histories—I’ve met a lot of heroes. The project feels like an emergency. I wish I could say more. The book is under contract with AK Press. For now I will say: Visit PlanCPills.org to learn about how people can and do get abortions today. Also, donate to the National Network of Abortion Funds.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Pat Parker. One of the first openly lesbian poets, Parker wrote about race, class, queer sexuality and love, and later, environmental injustice and chronic illness. In addition to being a writer, Parker was a radical health worker and a revolutionary. She’s known in Black, lesbian, and queer feminist poetry circles. But readers in more mainstream literary and academic contexts often overlook her. Reading Parker and learning about her revolutionary life has profoundly changed mine. She’s shown me that poetry can play an actual role in remaking the world. You know that Oakland abortion clinic I mentioned? Parker worked there for a decade. If you don’t already have it, get yourself a copy of The Complete Works of Pat Parker edited by Julie Enszer.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I got an MFA and then a PhD. I loved being a student. I was the first person in my family to get those types of degrees. It’s unfair that paying for an MFA is often what allows people, if they’re lucky, to make the types of connections with writers, editors, and presses that eventually help them get published. But it’s a reality. Most people don’t get big scholarships or fellowships to go to grad school. So if you’re not rich, you go into debt. I did it. I took out loans. Later I got publications. What am I saying? Well, I’m in debt. Creative writing programs and the whole concept of literary prestige are classist. Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young wrote a good article about it called “On Poets and Prizes.”

That said, taking time to develop a writing practice in community with others is powerful, and it will help you “become a writer,” whatever that means to you. So yes you could do it in an MFA program. But you could also do it in a community workshop or online workshops offered by independent, unaffiliated poets. Or by getting involved with or even starting an alternative education space like the Operating System, Threshold Academy, or Wolfemme+Them collective.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Interventions for Women?

I make arguments in this book. Right now I really want to be talking with people about what’s going on, because it’s crazy out there. I tried to write poems that would help fuel real talk. Maybe I’m wrong about what’s going on, I don’t know. Even if I’m wrong, I hope that in my wrongness I might help bring some edge to conversations.

Last spring I participated in a small antiracism workshop series led by Judy Grahn. All of us were white, though we came from different class, regional, and religious backgrounds. The purpose of the group was to confront and articulate the white settler master logics in our families that we witnessed and internalized growing up. The conversations were painfully honest. The group helped me to better understand arguments I think I’m trying to make in two of my poems, “interventions for women” and “meat habitats.” I want the poems to invite readers of different raced, classed, and gendered experiences to think about how gender oppression and sexual violence perpetrated in white households and by white people and institutions are inextricable from the environmental violence of the racist settler industrial food system. What surprised me was that I found I could use poetry to interrogate the white supremacist logics that had started constituting my mind and body when I was very young.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

I woke up one morning in San Francisco last year, and the sky was orange. It never got light out. I spent the day inside with the windows shut and finished writing the last poem in the book. By the end of that day, I felt clear about the fact that the book needed to be done.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I trust myself first these days. But I always share my work with friends before publishing. Sometimes the best readings of your work come from people you love and who love you—your best friends. But not always. Sometimes they come from readers who are mostly strangers to you.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

In a poem about feeling some overwhelm around her jobs to care for family, friends, and community, Pat Parker wrote, “The next person who asks / ‘Have you written anything new?’ / just might get hit.” Parker is saying a lot here. One important thing that I think she’s saying is: Don’t stress if you’re not writing all the time, because you’re probably busy helping keep the people you love alive, and for that you’re a fucking hero.