This week’s installment of Ten Questions features CAConrad, whose latest poetry collection, AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration, is out today from Wave Books. In AMANDA PARADISE, CAConrad uses a (Soma)tic poetry ritual to call forth poems from the natural world. One element of their “Resurrect” ritual is to lie on the ground while listening to audio recordings of animals who have gone extinct or are on the verge of extinction. They are interested in the “concept of vibrational absence”—how the world is fundamentally altered by loss. Through the ritual they also access the ongoing reverberations of other plagues: the AIDS crisis and coronavirus pandemic. But if rooted firmly in the frequency of the immediate world, the poems are equally oriented to the horizon. In the long poem “72 Corona Permutations,” they ask, “let us please / consider / the things / we do not want / to return to normal.” The alternative to “normal” can be found in the poem itself, which urges: “argue for beauty / always argue for beauty / it is the one fight we are / forbidden to surrender.” CAConrad is the author of numerous previous books of poetry, including ECODEVIANCE: (Soma)tics for the Future Wilderness (Wave Books, 2014) and While Standing in Line for Death (Wave Books, 2017), which won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. They have received fellowships from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, the Lannan Foundation, and MacDowell, among other institutions. They teach at Columbia University in New York City and Sandberg Art Institute in Amsterdam.

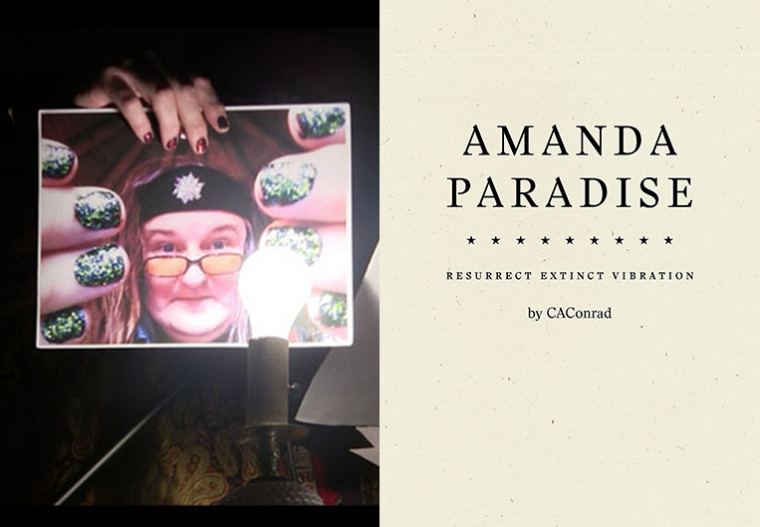

CAConrad, author of AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration. (Credit: Alice Wynne)

1. How long did it take you to write AMANDA PARADISE?

For several years I wrote this book with the aid of a (Soma)tic poetry ritual involving the former lives of animals that have become extinct in my lifetime.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

That I enjoyed writing it is the best answer. The ritual I used involved lying on the ground across the United States while flooding my body with field recordings of recently extinct animals. When initially planning the ritual, it appeared to have the potential of depressing me. I had a contingency plan for dealing with that possibility. Instead I was overwhelmed with euphoria after each session with the recordings. Processing my guilt of being upset from enjoying the ritual helped me understand how much survivor’s guilt I have from the many friends and lovers who died of AIDS. It has taken me years to write about the trauma I live with from those early years of watching the disease destroy beautiful, talented, powerful souls. As difficult as it was, AMANDA PARADISE became the place where the loss of loved ones and the destruction of entire ecosystems and their creatures braided themselves in the poems. The most important lesson this book taught me is that survival depends on falling in love with the world as it is, not as it was.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Especially since I began using (Soma)tic poetry rituals, the poems are part of my breathing, eating, and sleeping. I have been making poems since 1975, but if I did not have poems, I would probably join my friends who go on meditation retreats, but as it is, living with poetry as I do, all my living is a meditation.

4. What are you reading right now?

News like ProPublica and poetry are my daily reading. Here are some of my new favorite books: Funeral Diva by Pamela Sneed, SEKXPHRASTICS by Jane Goldman, A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure by Hoa Nguyen, CURB by Divya Victor, Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz, Now It’s Dark by Peter Gizzi, Yes, I am a corpse flower by Travis Sharp, RoseSunWater by Angel Dominguez, and A Feeling Called Heaven by Joey Yearous-Algozin. Many other poetry books, chapbooks, and magazines make for an exciting, overwhelming wealth of poetry in the current moment!

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

When I hear the word “author,” I think of novels, and I do not read them.

Poets in general need more recognition. Have you seen how feeble the poetry sections are in most bookstores you visit? When I walk into a bookstore and there is no poetry at all, I walk out while openly sharing my disgust, vowing never to return!

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

When poetry becomes part of your everyday life, it is poetry that becomes an impediment to other things. An old boyfriend helped me understand this years ago. We were supposed to go to a movie together, but ten minutes before we were about to leave the conversation with a poem began. He said, “Okay, let’s go,” and I said, “I cannot go, sorry.” He left in anger, and I shook off his reaction so that I could reenter where I was at with the poem. He had every right to be angry because it was not the first time I had done this to him. Still, I am not willing to compromise because the moment you walk away from the conversation with a poem, you lose it, and it will never return. I lost a job once for locking myself in the bathroom to write a poem, but I found another stupid job and got to keep my poem!

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started AMANDA PARADISE, what would you say?

I would go back to the day when I was sitting on the forest floor in New Hampshire working on the (Soma)tic poetry ritual called “Mount Monadnock Transmissions.” I designed this ritual to overcome a debilitating depression over the rape and murder of my boyfriend Earth and the brutality of the police responding to queer death. It was a moment of absolute clarity for me, where I thought, “He changed his name to Earth at a time when humans have raped, tortured, and scorched the planet. And the men who killed him did exactly that to him.” I burst into tears from this epiphany, but that was when I could see the subsequent (Soma)tic ritual for the animals trying desperately to survive the extraordinary danger of top predator human beings. Those poems compose AMANDA PARADISE: Resurrect Extinct Vibration. The location in New Hampshire was the MacDowell artist residency, and I am grateful to all the good people working there who made all the conditions for me to be comfortable enough to have the epiphany in the first place. But your question is, what would I say to that earlier self? I would say, “You cannot see it yet, but you just found the entrance to an even larger healing inside yourself.” When we take care of ourselves, our strength prevails more obstacles to our creativity and our path to joy.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

I do not finish poems; I abandon them. My feeling is those of us with books in our lifetime do not mind deserting our poetry, or at least we grow accustomed to the abandonment.

One of my favorite poets is Iliassa Sequin. She has only one book because she never abandoned her poems and worked on the collection her entire life. After she died in 2019, her spouse and publisher began making the book, which came out just several months ago.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Trusted friends, but I completely trust the spirits whispering these poems to me.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I have spent my life resisting the endless unsolicited advice people love to offer about who I “should” be reading and how I “should” be writing.

Instead let me share something I have come to understand about a long-standing belief among poets that has cost too many lives and destroyed entirely too much potential happiness.

For decades poets have told me they write their best work when they are depressed or from the pain when a lover leaves, something that steers them into melancholy. When I teach creative writing, this often comes up, and I tell the poets in my class that I understand, but I also believe it is not exactly what we think it is.

We live our lives with our list of daily routines, from washing our bodies to obeying traffic signals on our way to work. There is so much to remember to get through the day. When tragedy disrupts our routines, suddenly all of our attention is centered on that loss. It is in the focus of loss where many believe they can write better. Focus, the keyword.

It is crucial to learn that the focus the depression offers helps us write, not the depression itself. After we finally understand this, we see how we can orchestrate any focus we want, to write whenever and however we want! (Soma)tic poetry rituals have given me eyes to see the creative viability in everything around us for the poems!