This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Callie Siskel, whose debut poetry collection is out today from W. W. Norton. In these finely wrought lyrics, Siskel offers a personal history in the shadow of a father’s early death, considering how absence and loss can shape a life as much as any tangible presence. The poems are simultaneously concrete and philosophical, with snapshot memories from childhood through adulthood captured in sensate detail, then mined for revelation—which remains always just out of reach, much to the consternation of the self-aware speaker: “Why this need to eke out meaning / from every errant thing?” she asks herself in “Prophecy in Blue.” The poems capture the fragmentary quality of traumatic grief, as they seize upon remembered moments and attempt to wrestle them into narrative coherence. Poems of personal experience are interspersed with ekphrastic pieces contemplating the works of Caravaggio, George Clausen, Monet, and others: “When told I look like a man’s image / of a woman, I believe it,” she writes with wry humor in “Jeanne,” a poem titled for Amedeo Modigliani’s wife, a frequent subject of the artist’s paintings. The heavy permanence of canonical art becomes a counterpoint to the ephemerality of human life, a contrast that by turns soothes and troubles the speaker, “[t]hat we would be outlasted / by a heavy coat of paint.” Victoria Chang praises Two Minds: “Siskel’s poems are wise and thoughtful, quietly evocative.” Callie Siskel’s poems have appeared in the Atlantic, Kenyon Review, Yale Review, and elsewhere. The author of Arctic Revival, winner of the Poetry Society of America Chapbook Fellowship, she is a former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and holds a PhD in creative writing and literature from the University of Southern California.

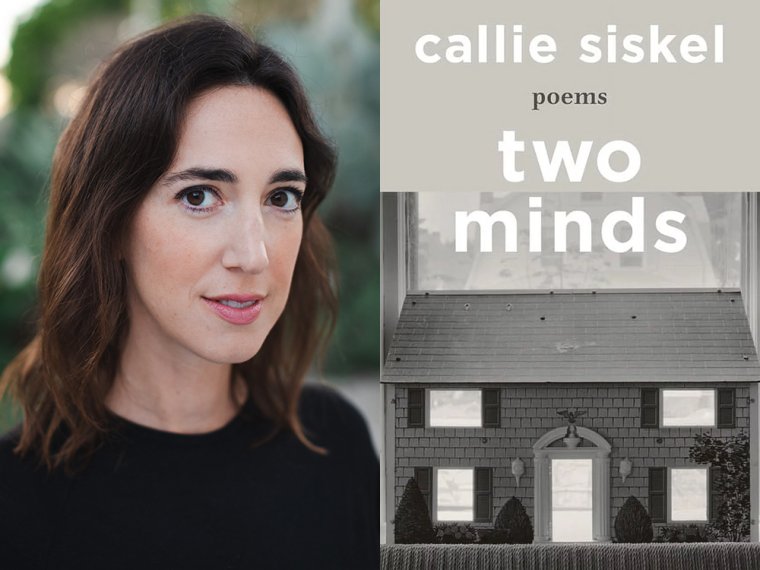

Callie Siskel, author of Two Minds. (Credit: Lauren Kallen)

1. How long did it take you to write Two Minds?

I wrote the oldest poem in the book, one of many elegies for my father, twelve years ago. Just now I’m realizing that I’ve been writing the book as long as I had my father—I was twelve years old when he died. That symmetry also feels asymmetrical (my time with my father feels so much longer). As someone who looks for meaning everywhere, I feel some sense of catharsis knowing my efforts to inscribe him in writing took as long as he existed physically in my life.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Writing about loss was challenging—dilating that painful moment in time, looking backward. One of the questions underlying Two Minds is to what extent grief shapes who we are. At one point the poems wanted me to answer that question “completely.”

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write at my computer when I feel inundated by an idea or a phrase. Right now I’m working on a series of linked poems, which has sustained momentum. I’ve written late into the night and first thing in the morning. The time of day is less relevant to me than the sense of urgency that I have to feel in order to commit to the page. I’ve tried writing by hand, to free myself from my impulse to edit as I write, but I’ve recently embraced that my process is to edit as I go; I prefer to create by taking things away. Revising while writing allows me to distill my thoughts and to reach for a clearer line of communication. Once I’ve reached that place, the poems come much more easily.

4. What are you reading right now?

Eliza Gonzalez’s Grand Tour, Leslie Jamison’s Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story, Saskia Hamilton’s All Souls, and Sigrid Nunez’s The Vulnerables, all of which are keenly about transformation. I like to read poetry and prose at the same time—often poetry in the morning with coffee and nonfiction/fiction in bed.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

Reordering until the editing voice inside my head quieted and I was able to read the collection front to back without the impulse to change it. I also had help. My teacher told me which poems she felt should appear earlier in the manuscript and which near the end. My friend told me to order it poem by poem, and to trust those movements intuitively. Breaking it into five sections also helped because it took some pressure off “the beginning” and “the end”—each section presented another chance to do it differently—and ambivalence and opposition are themes in the book.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I would! Maybe less for the sake of the degree than for the experience of having a number of years to focus primarily on writing and to build a community that lasts way beyond those years. I appreciated how the MFA empowered me to take my writing practice more seriously. The financial support and experience teaching creative writing to undergraduates was also extremely valuable.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Two Minds?

The poems that came the easiest, the most suddenly and least painfully, are among my favorites in the book. The same is true for some of the poems that are furthest away from the direct subject of loss. Perhaps that makes sense—that I’d like the poems less bound up in struggle—but I tend to place a lot of value on difficulty, whether that be emotional or technical, and writing the book taught me that there is also beauty in lightness, mindlessness, and ease.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Two Minds, what would you say?

I would be tempted to say, “You will publish a book.” But I wonder if that would have eased the nerves I needed to write in the way that I did, without thinking about how the poems would one day become public. While I am always thinking about a reader—singular—I find that writing uninhibitedly, without a larger audience in mind, is the only way for me to disclose and excavate my inner life. Perhaps I would just say, “You will finish a book,” and leave it at that.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

There were the things I did to support my writing—teaching, leading book clubs, editing, copywriting—and the things I did to nourish my writing: academic research, therapy, and hiking. I was doing a lot of hiking with friends in the year before I finished the book, and I credit it with allowing me to see things differently, and, conversely, to live more in my body than in my head. I think the arc of writing a poem is similar to the experience of ascending and descending physical terrain. Ideally the view at the top surprises and reorients you.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

If you already know what you want to say, if you are attempting to transcribe the past, it won’t come alive on the page.