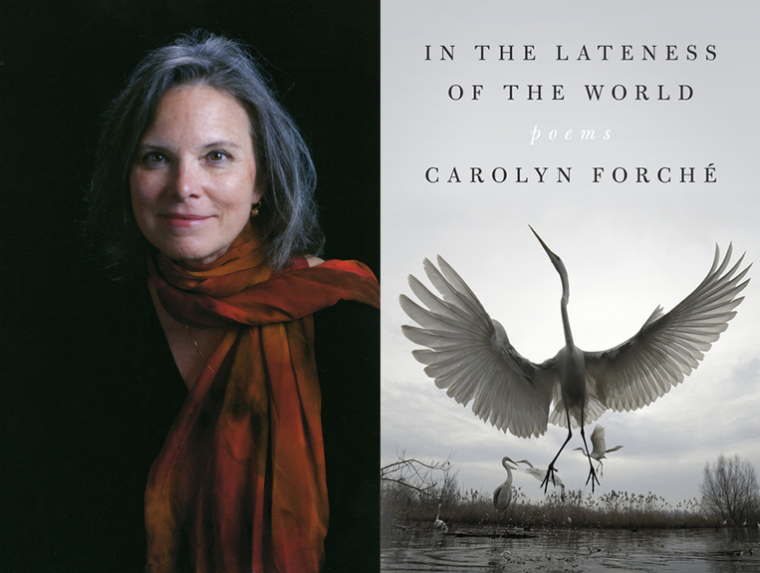

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Carolyn Forché, whose fifth book of poetry, In the Lateness of the World, is out today from Penguin Press. In her first new collection in seventeen years, Carolyn Forché meets her readers at the end of the world. The first poem, “Museum of Stones,” catalogues civilization by its ruins: “stone from the hill of three crosses and a crypt,” “stones, loosened by tanks in the streets,” and those “newly fallen from stars.” Nearly unbearable darkness follows, yet Forché presses forward and remains present. She imagines herself on the boat alongside refugees, and she walks among the beetle-infested trees. She finds no other path but resilience. “there is nothing / that cannot be seen,” she writes, “open then to the coming of what comes.” Carolyn Forché is a poet, translator, and activist whose work has been translated into over twenty languages. Her books of poetry are Blue Hour, The Angel of History, The Country Between Us, and Gathering the Tribes, and her memoir, What You Have Heard Is True, was a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Her many literary honors include the Academy of American Poets Fellowship and the Windham-Campbell Prize. She lives in Maryland and teaches at Georgetown University.

Carolyn Forché, author of In the Lateness of the World. (Credit: Don J. Usner)

1. How long did it take you to write In the Lateness of the World?

The earliest poem was written in 2003, and the most recent in 2018, so fifteen years. In the past I published a book every decade or so, beginning in my twenties, so this one took longer.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I didn’t write a book so much as I wrote individual poems during those fifteen years, and discovered the connections among them, subtle or apparent. The greatest challenge was in recognizing which poems belonged to this book and which did not, and in allowing the whole of it to evolve, rather than to determine in advance what it would be.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in small notebooks, often in the early mornings when it is still dark, but also throughout the day, most days, and everywhere I happen to be. I like to write while traveling, especially on trains.

4. What are you reading right now?

At this moment, the stack includes Hanif Abdurraqib’s A Fortune for Your Disaster, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo’s Children of the Land, Jenny Offill’s Weather, Marcelline Delbecq’s Camera, the new issue of Lapham’s Quarterly on memory, Mark Nowak’s Social Poetics, and Jeff Sharlet’s This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

There are many, but I will name two, both working-class writers: Meridel Le Sueur and Edward Dahlberg. Read Le Sueur’s The Girl and Dahlberg’s Because I Was Flesh.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Perfectionism, which has nothing to do with the work itself, but which leads at times to procrastination, not only of the writing, but of releasing it into the world. That, and the demands of contemporary life that distract us all. Sometimes illness has stood in the way of my work, and also manmade disaster—years were swept away when a broken water-main flooded and destroyed our house. Cancer and water. On the other hand, it is possible that these interludes allowed the writing to deepen.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Patience, and the ability to read a work on its own terms, to comprehend it from within. I’m fortunate to have found these in both my literary agent, Bill Clegg, and my editor, Christopher Richards.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

There should be more people of color on publishing house staffs at all levels, which entails, among other things, creating entry-level positions well enough paid that a person could survive on salary alone. Unpaid internships are possible only for an economic elite. Corporate-owned houses should emulate the independent houses of the past, more generously subsidizing serious literary art, including poetry, with profits from their more commercial endeavors. It’s sad that poets’ first books must win contests in order to be published. As for the “writing community,” I would say that they are plural—there are communities of writers, rather than a single community, and they exist everywhere, not only in the coastal cities. There should be greater recognition of this.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

For the past thirty-five years my most trusted reader has been my husband, Harry Mattison. He is a photographer, but we both began reading and writing poetry as children. Very early in our relationship he recited Hart Crane to me while crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. Among his few possessions then, other than cameras and darkroom equipment, were poetry books, and Robert Creeley was among his closest friends. From the beginning, he knew intuitively how to respond to my work, and his readings have helped me immeasurably.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Goethe’s “Do not hurry; do not rest” serves as the epigraph for Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, where she offers most of the best advice I have encountered, including: “You must demolish the work and start over. You can save some of the sentences, like bricks.” And: “Get to work. Your work is to keep cranking the flywheel that turns the gears that spin the belt in the engine of belief that keeps you and your desk in midair.” There is also something there, too, about how long it takes to write a book, as much or in my case, more than a decade. I found this to be comforting.