This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Clare Sestanovich, whose debut story collection, Objects of Desire, is out today from Knopf. The eleven stories that make up Objects of Desires are filled with subtle yet significant gestures. A boyfriend “close to getting angry” goes to lie down and faces the wall; a mother falls asleep in her daughter’s bed after she leaves for college; a husband pauses to mark his place in the book he is reading when his wife asks for a divorce. Throughout the collection, Sestanovich remains this attuned to the often precarious dynamics between her characters. She reveals how friends, family, and lovers perform or fail to perform for one another—how there will always be mystery, miscommunication, and strangeness even in the most intimate of relationships. “Astonishing—one of the best story collections I’ve read in a long time,” writes Brandon Taylor. “The stories in Objects of Desire are subtle and sophisticated, written with sensitive lucidity and warmth; their emotional effects are brought about naturally, almost indirectly, and one leaves each of the stories feeling a little homesick.” Clare Sestanovich is an editor at the New Yorker. Her fiction has appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review, Harper’s, and Electric Literature. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

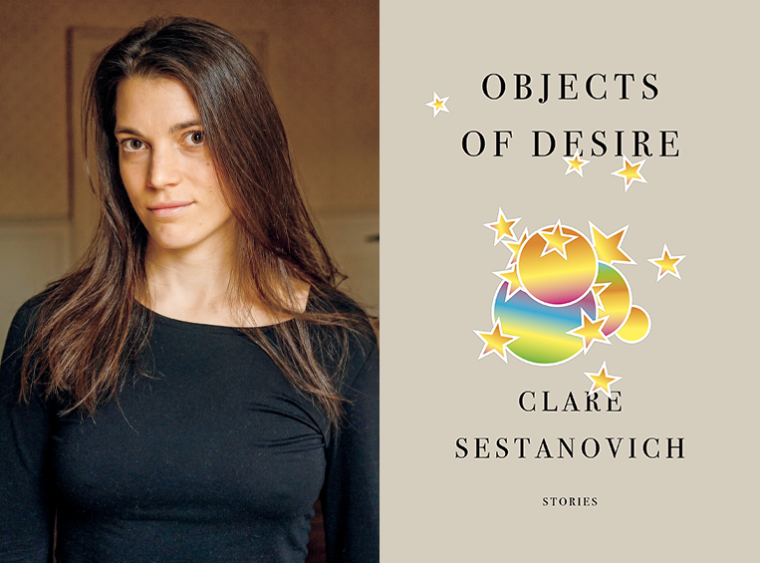

Clare Sestanovich, author of Objects of Desire. (Credit: Edward Friedman)

1. How long did it take you to write Objects of Desire?

The oldest story in this collection is five years old, and when I wrote it, I had no idea that I was writing a book. It took another year or so for me to realize, and even then, I didn’t quite believe it. I never referred to “my book.” Other people sometimes called it that, which was surprising and flattering and a little preposterous. It was just a lot of words on my computer! But up until the very last minute, that’s all a book ever is. The newest story was written a year ago, at the height of the pandemic, when I thought the collection was already finished. Which is all to say: The book often knows more, and knows better, than you do.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

In the early months of writing the book, I turned down a job, because it was a job that I suspected would give me meaning and purpose, and I was afraid that if I took it I would use it as an excuse to abandon writing—a vaster but far less stable source of meaning and purpose. I don’t think this was an especially brave decision—had I not found another way to make money, it could simply have been arrogant and unwise—but it was a difficult one, and I lost a lot of sleep over it. The agonizing helped, though. I put my eggs in this basket, this book, and after that, I had to do whatever I could to find out what would hatch.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

That hardest part was that every day I had to decide—again—to keep writing it.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write early every morning. This isn’t really a preference, or a principle, it just happens to be the only schedule that I can follow while also doing my day job. I regret that early risers seem virtuous and night owls seem cool. I would much rather be cool!

5. What are you reading right now?

I just finished A Shock by Keith Ridgway and started Erasure by Percival Everett.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Mary Robison is funny and unafraid and knows how to break your heart in two sentences. Why aren’t we all talking about her?

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I wish there were more paths to being in it. Communities so often just mean institutions. And getting inside one institution usually requires passing through another, which in turn requires pushing open the door at yet another. I hope we can remap the labyrinth, because too many people get lost in it.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Objects of Desire, what would you say?

I wouldn’t tell her that it was going to work out. The negative capability that is required to write without certainty but with conviction is surely the most important skill you can acquire. I haven’t yet, but every day that I lose and find my faith—in myself, in my prose—feels like one step closer to relinquishing the need to believe in anything other than the process.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

For a long time my writing felt a little bit like a secret. I wasn’t hiding it on purpose, but other people only ever glimpsed it in bits and pieces, and most of them never saw it all. My agent, Bill, was the first person who ever saw the whole thing, and it’s true what they say about being seen: It makes all the difference. I imprinted on Bill the way ducklings do. You know you trust a reader when they tell you to cut your first sentence or your last sentence—those sacred darlings!—and your only reaction is, of course.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My greatest menace as a writer is self-doubt, which is why I return so often to the advice that Martha Graham gave to Agnes de Mille: “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open…. No artist is pleased…. [There is] no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”