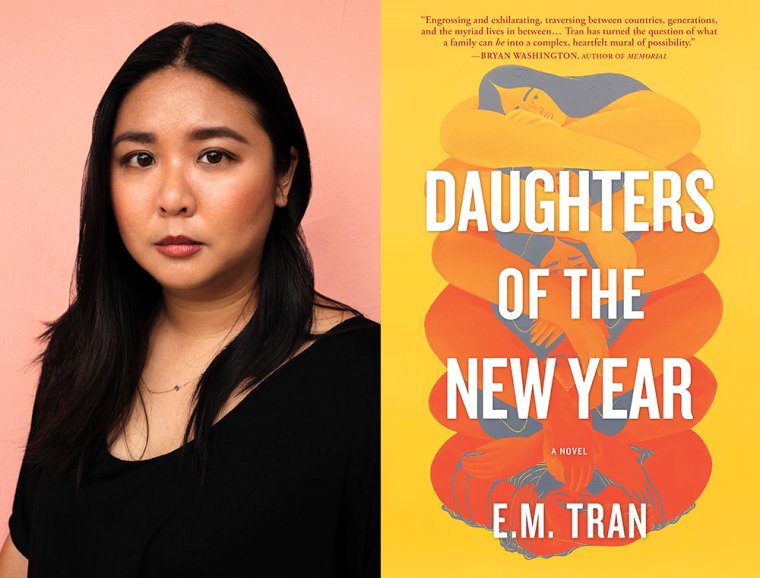

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features E. M. Tran, whose debut novel, Daughters of the New Year, is out today from Hanover Square Press. In this multigenerational narrative, a family of Vietnamese immigrants is haunted by ancestral secrets. Matriarch Xuan Trung, a former beauty queen who fled her home nation for New Orleans after the fall of Saigon, seeks to protect her three daughters by tracking their fortunes through their zodiac signs: Dragon, Tiger, and Goat. Each strong-willed daughter blazes a unique path in the United States: The eldest, Trac, is a driven attorney and queer woman; middle-child Nhi competes as a contestant on the Eligible Bachelor reality show, filmed in Vietnam; and youngest Trieu is a writer set on understanding a family history marked by silences and gaps in the record. Tran tracks the experiences of these four women, interweaving their stories with those of female ancestors whose lives influence the present more powerfully than anyone might suspect. Bryan Washington calls Daughters of the New Year “engrossing and exhilarating.... Tran has turned the question of what a family can be into a complex, heartfelt mural of possibility.” E. M. Tran’s stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in Joyland magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Thrillist, and Harvard Review Online. Her essay, “Miss Saigon,” won Prairie Schooner’s 2016 Summer Nonfiction Prize and the journal’s Glenna Luschei Award. She completed her MFA at the University of Mississippi in Oxford and a PhD in creative writing at Ohio University in Athens.

E. M. Tran, author of Daughters of the New Year. (Credit: Melissa Tran)

1. How long did it take you to write Daughters of the New Year?

I started writing the book in 2018, and it took me three years to finish the first draft. I was enrolled in a doctoral program at the time and had been reading books from my comprehensive exams list. After reading How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, a vision for how I wanted to embark on this project immediately clicked into place. I worked on the book pretty consistently until I graduated from my PhD program in 2020, and then continued to work on it during the imposed isolation of the pandemic.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

When I was early in the writing of this book, I attended the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and brought the first two chapters to my workshop. I was calling it a novel but secretly had the insecurity it was more like a collection of stories. Because the book moves backward, the chapters can be quite episodic, and I struggled with making sure the book felt like a cohesive, singular work. But when I described it to one of my friends at the conference, she said quite assuredly, “That sounds like a novel to me.” That was really encouraging, and when I went back to writing, I tried really hard to make sure that a sense of momentum, a moving through narrative that would accumulate into some collective end, was realized. This was really challenging, but I had to shift my mindset. The same issue exists when you’re writing time going forward, but we’re just used to thinking about “moving forward” as a way to build narrative. Tension and narrative movement can still accumulate when you go backward. It just looked different, and I had to really get comfortable with that when I was writing.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in my office, usually at night because I do it after my day job, unless I’m writing on the weekend. Sometimes I write every day for a week, and other times I have a week gap between my writing sessions. I’m really a person who writes for long, productive bursts and then might have days and days of no writing.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m currently reading Trust by Hernan Diaz. It’s incredible—he nests four different fictional books within the book. I’m really interested in how those different stories contradict or reshape the reality that each perspective has presented to the reader.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Like I said, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents was a big influence. That book also moves backward in time and focuses on the four Garcia sisters. I was directly inspired by Julia Alvarez’s narrative structure: Daughters of the New Year similarly moves backward and focuses on the perspectives of the Trung women. Also, I’ve always idolized Toni Morrison. The first book I read of hers was Song of Solomon, on a family trip to Paris in 2008, and I literally did not want to put the book down to explore one of the greatest cities in the world. She showed me how to write complex women in Sula, Beloved, and The Bluest Eye, and I consistently look to Morrison for beautiful, dense language. More broadly, I feel like my book is in conversation with and influenced by any writing about diasporic and Asian American experience: Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Celeste Ng, Ocean Vuong, and so many more. When I was a kid, trying to find narratives where I could see myself, the literary landscape felt sparse. Especially because I didn’t know where to look, and the stories I wanted to hear weren’t taught in school. I didn’t find these books until I went to college. There are so many different versions of the Asian American story out there, and I’m indebted to all of them.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Daughters of the New Year?

I was surprised to find, in the editing process, how much of my present life continually got added into the reworked draft. I had always viewed the editing process as a carving and shaping of what was already there, like sculpting a block of marble. But working on a book is such a long, arduous, enormous process. I spent enough extended time editing that, as things happened in my life, they became inextricable from what I was editing into the book. It changed how I viewed the writing, what I used to view as an embodiment of who I was in the past when I wrote it, and turned into an ever-evolving, constantly shifting narrative object in the present.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My agent told me not to let career jealousy get in the way—there’s space for your story.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Daughters of the New Year, what would you say?

I’m pretty sure any advice I offered to my earlier self would be ignored. I’d probably say, in the words of the wise Kris Jenner, “You’re doing amazing, sweetie.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

There were so many random things I did that helped this book along. I started doing calligraphy. This was a wonderful break from writing, but I was still writing in a different medium. I was also a rare-books librarian’s assistant and worked in a rare-books vault. Something about being in constant physical contact with old books helped ground me when everything about writing a book today is digital. I would go through the books, manuscripts, and leaves and find little story details, history, or ideas. I did some research on the history of rubber plantations, the social elite in Vietnam, and the Trung sisters and Lady Trieu. And I watched a lot of The Bachelor and The Bachelorette—but was that work?

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Aim for one hundred rejections—it recasts the rejection as a goal achieved, rather than a failure. And along the way you’re sure to have a success you didn’t expect.