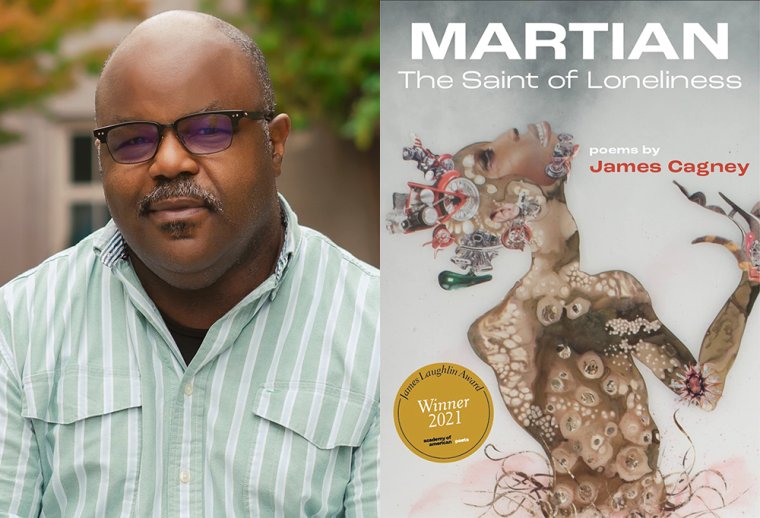

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features James Cagney, whose second poetry collection, Martian: The Saint of Loneliness, is out today from Nomadic Press. Winner of the 2021 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets, Martian is a cri de coeur that probes feelings of alienation and rage in the face of systemic corruption and state-sanctioned violence. “I come from a poisoned land that recycles children / into artillery shells / & where dark skin is good as / an invisibility cloak / until the police arrive,” Cagney writes in “America, I Am.” In freewheeling, dexterous lyrics, Cagney’s speakers curse and mock their oppressors, mingling elegiac language with bitter humor that evokes laughter through tears: “Ask Siri: How can I get home without being victim or / witness to gun violence?” Cagney writes in “Bullet Gumbo.” Yet a tenderness pervades the collection, with anger giving way to sorrow and estrangement, embodied in the figure of the extraterrestrial: “Such complex algebra // just to land in welcoming arms,” Cagney writes in the book’s title poem. This sense of distance, while painful, also functions as a kind of saving grace, an ability to perceive beauty in unlikely places: In “Ode to My Towel,” for example, this most mundane of objects becomes a “soft, blind bird” that knows the speaker “better / than any lover.” Matthew Zapruder praises Martian: “These extraordinary new poems burst off the page, wild controlled explosions demanding our attention with their intelligence, frustration, wisdom, and love.” James Cagney is the author of Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory (Nomadic Press, 2021), winner of the PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award. A Cave Canem fellow, he lives in Oakland.

James Cagney, author of Martian: The Saint of Loneliness. (Credit: Rohan DaCosta)

1. How long did it take you to write Martian: The Saint of Loneliness?

I think the poems started gathering around 2016, if not a touch earlier. Many were in response to and in allegiance with social justice movements. Several poems were written during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic stay-at-home order. By then I’d already submitted the manuscript for Martian. But before we could edit it I pulled about seven pages worth of poems and put in twelve new pages I’d written in my kitchen during the spring of 2020.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Waiting for its publication. The pandemic and supply crisis shattered every industry and affected all of us. I think I got the acceptance letter from the publisher in January 2020, and then the world went dark. In my mind I watched that project age and became scared it would be irrelevant or pointless by the time it came out. I quite literally held my breath for a year or two.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in the mornings. I was called physically back into the office last year and was happy to go out of boredom from being home. Eventually I started going in an hour early, just to write. I realized I could work quietly and in peace for a good hour before folks started wandering in. It became an ideal way to start my day. I have an 11 x 17 notepad, and if I can finish three or four pages in a session, it feels really good. I start the day already feeling as if I accomplished something.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished two stunning collections, Phillip B. Williams’s Mutiny and Roger Reeves’s Best Barbarian, which are as incredibly powerful as they are inspiring to me. Such beautiful, deep work. Moon Witch, Spider King by Marlon James is overwhelming and genius; I don’t understand how he does it, I can only admire him from a distance. And I was very interested in Isaac Butler’s The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act, a biography of method acting, one could say. I have a better understanding of it thanks to that book. It was interesting to me that Black actors were not heavily involved in or accepted by the method. I didn’t seriously think about that until reading that book.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

It took a while. My first collection was an autobiography in poetry, and I saw the arc of how to build it very clearly. Martian, however, assembled itself like a collage. It told me how it wanted to be structured. I don’t see it having a clear through line. But there are definitely poems that are related to one another. The entire collection represents how I was feeling and what I was experiencing for the past four or five years, if not longer.

6. How did you arrive at the title Martian: The Saint of Loneliness for this collection?

“Martian” was one of the poems I was most proud of in the book, and I never considered any other namesake. I’ve held the words “the art of loneliness” for a very long time, since I was in my twenties, actually, thinking I’d use that as the title for something. But as this book was being assembled, it struck me as amusing: that image of a martian as a saint. I know there were some memes about that, but truthfully I was thinking about feeling alienated, floating in space, feeling lonely and wondering who would be an ideal saint to pray to when you’re stuck like that.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Martian: The Saint of Loneliness?

That a book is its own entity, somehow. It’s not conscious, but it’s responsive. It has its own intelligence. I was surprised to change a chunk of it during the pandemic, and that change felt better, more appropriate for the entire project. I don’t know why. It was like words came up to me and demanded to get in on this new book project. That was my surprise. I’m not a writer, I’m a receiver for something I don’t always understand.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Martian: The Saint of Loneliness, what would you say?

I feel like I’m supposed to say: I wish I’d done something earlier, realized something sooner. But I couldn’t have written this ten years ago, and it would have been a different book if it’d been published before the pandemic, a worse or weaker book, I’m sure. Things happen when they need to happen. There would have been no reason to go back in time, beyond leaving myself a message: “Yeah dude. You’re still gonna need to wait.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I don’t practice visual art, but I enjoy it. I’m not great at painting or drawing, but I learn a lot from visual artists and enjoy communicating with them through language. I enjoy sometimes thinking of my writing as “word paintings.” I periodically need to engage with visual art in order to help me resee, rethink, reconsider my world and find new approaches to creating poems. I need periodic access to museums and visual artists. I need art to help rebalance me.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Kill your precious darlings, which has been widely attributed to William Faulkner, but I heard it years ago from the late Bay Area poet David Lerner. That and Elmore Leonard’s advice: “Anything that sounds like writing, cut it.” I know poets are supposed to be pretty with our language, but sometimes enough is enough. I am guilty of overkill and working too hard to make a line poetic.