This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jennifer Lunden, whose book, American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life, is out today from Harper Wave. Part memoir, part medical history, and part exploration of the life of American diarist Alice James, this layered narrative considers the toll chronic illness can take on individuals, particularly when their symptoms are misunderstood or ignored—a far-too-common occurrence in a healthcare system that fails to meet the needs of many, particularly women, people of color, and the poor. Lunden begins in 1989, when debilitating exhaustion stops her life in its tracks. As her despair deepens amid doctors’ inability to diagnose her, she discovers a biography of Alice James, whose struggle with poor health mirrors Lunden’s own. Dismissed by her family and the medical establishment as “hysterical,” James becomes a kind of spirit guide for Lunden as she works to understand her own illness and the larger sociopolitical and economic systems that have contributed to it. Kirkus praises American Breakdown, calling it “an alarming chronicle of catastrophic chronic illness and a passionate plea for health care reform.” Jennifer Lunden’s essays have appeared in Creative Nonfiction, DIAGRAM, Orion, River Teeth, and elsewhere. The 2016 recipient of the Bread Loaf–Rona Jaffe Foundation Scholarship in Nonfiction and a former therapist, she lives in Maine with her husband, the artist Frank Turek.

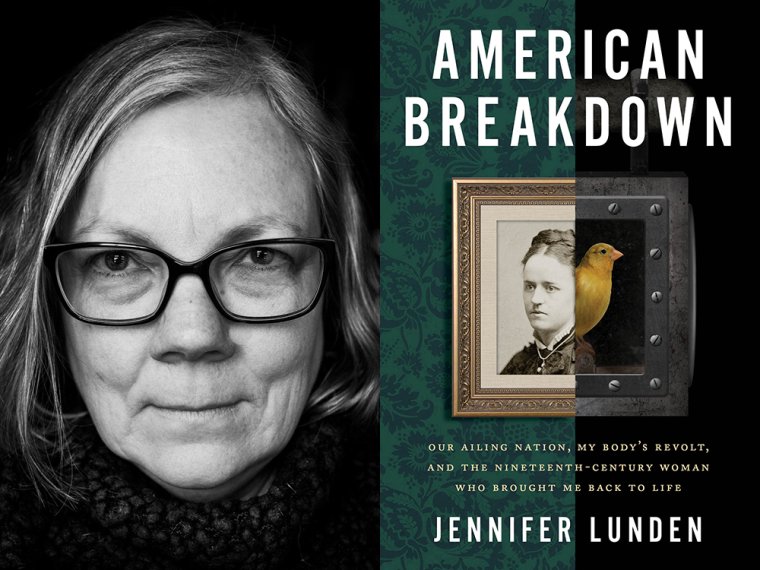

Jennifer Lunden, author of American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body's Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life. (Credit: Travis Widrick)

1. How long did it take you to write American Breakdown?

Well, the seed for American Breakdown was planted in 1994, when I read Jean Strouse’s brilliant biography of Alice James, who was a witty, brilliant, and chronically ill diarist, sister of the writer Henry James and the psychologist William James. By that time, I was twenty-six years old and had been sick for five years with what was then known as chronic fatigue syndrome, now also known as myalgic encepthalomyelitis or ME/CFS. The illness had devastated me, laying waste to the rich, fulfilling life I had envisioned for myself. While reading about Alice, it felt like I had met my soul sister. Her illness—neurasthenia—was so similar to mine. I wondered if they might be the same, separated by a little over a century.

I was studying for my bachelor’s degree in English at the time, then my master’s degree in social work, so I wasn’t able to begin my research until 2001. At the time, I found there were just a handful of scholarly papers discussing the possible connections between ME/CFS and neurasthenia. Since then, several writers with ME/CFS have explored this question. I’ve come to say that I’m ahead of the curve but behind the eight ball: I’m a really slow writer. I researched the book for six years before I felt confident enough in my knowledge and ideas to begin writing. That was in 2007. But I was working part-time and living with a disabling chronic illness. That, combined with the amount of research required for the many threads of this book, made for really slow going. I finished in 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I think the most challenging thing was just that I could never get enough time, and a book like this, with so many interwoven threads, needs uninterrupted swaths of time. I was a part-time therapist by then, trying to write the book on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays. But that was untenable. My therapist at the time started taking what he called “light weeks,” once a month, in which he only saw clients in the greatest need, and I decided to follow his example and squeeze four weeks of clients into three weeks. That made for three busy, stressful workweeks for me, but then I had a whole week to just lie in bed and write. And even that was frustrating. It was like a train leaving the station. The first two or three days I spent trying to remember where I left off and regain my rhythm. Just when I’d built up a head of steam, it was time to pull the brakes again.

Finally I learned to write a note to my future self to tell me where I left off and where I’d planned to go from there. I also did some cheerleading for my future self in those notes. That helped. But still, it was such slow going. It really helped when I finally sold the book and could work on it full-time.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When I was working on the book after I got the book deal, I was able to write every day, and that was ideal because then I wasn’t so likely to lose track of the threads in my head. But then I started dreaming of having weekends, the way many people do. Real weekends to just do whatever I want, which usually means unstructured time for reading. So that’s my goal once this book gets launched. Really, I’d like to attain a four-day workweek, which is something I advocate for in the book.

In the summer, my favorite place to write is in a zero-gravity chair in our backyard. There’s a squirrel who likes to come visit me and, although we’re in the city, we still have wildlife that captures my attention: house sparrows and crows, for example. Last year a mallard duck landed in our yard; I think she was looking for a place to nest. We also keep chickens. And stuff grows back there. Or here, as that’s where I am right now as I respond to these questions. I’m amazed how good it is for my body, mind, and spirit to be back here. It’s like a built-in mindfulness practice, because whenever I hear a rustling in the leaves or a crow’s caw, I stop being in my head and start experiencing the world with my body.

My husband also built me a desk for the front porch, so when I’m feeling more social (there’s a whole neighborhood out there!) I’ll sit there.

I write in bed, but my physical therapist—and by that I mean my body—doesn’t like it. So I have a recliner in the living room that I write in. If my energy is good, I can also sit up at my desk, which overlooks the chicken pen in the backyard. So basically, I have three to five writing stations, depending on the season.

Oh, and I’m a night person, so I often don’t get started till 3:00 PM or 4:00 PM, after I’ve checked my e-mail and swum or gone to appointments. Then I try to make myself stop at 9:00 PM so I can wind down and get to sleep at a decent hour, but I often stretch it to 9:30 PM or even 10:00 PM. I try to get to sleep by midnight.

4. What are you reading right now?

Well, I read many books at once. Many, many. But I just started reading Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, and I just want to sit back in my recliner and immerse myself in it until it’s done. The essay it’s based on, “What Do We Do With the Art of Monstrous Men,” which went viral in 2017, blew me away when I read it, and I’ve been waiting for this book for a long time. I think many of us have.

I’m also reading Chanel Miller’s memoir, Know My Name, which is about her experience as the Emily Doe who took Stanford University competitive swimmer Brock Turner to court after he was caught sexually assaulting her. The book won the National Book Critics Circle Award, as well it should have. She’s such a compelling, smart, and even funny writer and does an amazing job bringing the reader into her experience. It should be required reading for all teenage to college-age boys. It would be helpful for girls and women too, as long as it’s not too triggering.

Tricia Hersey’s Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto is helping me integrate into my body all that I have learned from my ME/CFS, and from the writing of my book, about the importance of rest in a capitalist and white supremacist culture that tells us that if we’re not stressed we’re not working hard enough.

I don’t read a lot of novels, but I love Deborah Gould’s writing. I always find it calming. The book I’m reading right now is The Eastern Book Two: Later On. She incorporates archival research into her work, so to me it reads like creative nonfiction, which is probably another reason I like it so much.

And I recently started reading Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice by Rupa Marya and Raj Patel. The title says it all, and I can’t wait to dig in.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Well, Jean Strouse, obviously, because she wrote the biography that changed my life. But if we go way back in time, my high school English teacher and writing mentor, Don Quarrie, was a big admirer of Hemingway and really trained me to “show, don’t tell” in my poetry. As a nonfiction writer I’ve since learned there is definitely a time and a place for both telling and showing, but I still love spare writing. So Sarah Manguso’s The Two Kinds of Decay had a big impact on me, because it’s so spare and clean and also because she successfully wrote about illness in a way that I found completely compelling.

I love Barbara Ehrenreich’s tone and point of view, and the book she cowrote with Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Expert’s Advice to Women, was influential in both content and delivery (though, of course, Ehrenreich’s voice is singular). I had already been working on American Breakdown for a year or two when I discovered Sandra Steingraber’s Living Downstream: An Ecologist’s Personal Investigation of Cancer and the Environment. It was the first time I read something that combined memoir with a larger story about health and the environment, and I was just so excited to see that someone else was doing what I was trying to do.

Sarah Vowell’s writing showed me how to write about history in a way that is fascinating and compelling. And Bill Bryson’s At Home: A Short History of Private Life showed me that it’s possible to write a really wide-ranging book that still holds together.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of American Breakdown?

I was surprised how poorly regulated the chemicals we bring into our homes and offices are. And my mouth was agape as I was reading about arsenic in nineteenth-century wallpapers, and in so many other products (including foods!) that people brought into their homes.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book ?

When I spotted the biography of Alice James on the shelf of a used bookstore, I knew that she too had suffered from a fatiguing illness. That’s why I bought the book. I had no idea how it would change my life.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started American Breakdown, what would you say?

I would say, “Right now it feels like there is no end to the suffering, and sometimes you think about suicide. But you are going to read a book that will inspire you to write a book, and even though right now there’s so much you can’t do, the writing of that book—which you can do in bed—will help you regain your sense of purpose. And this will help you live. And it will be so worth hanging in there. So hang in there, sweetheart.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Well, I didn’t realize until I taught graduate-level social work online in 2017 and 2018 how much my book was influenced by my education as a social worker. Social workers are trained to think about people and their suffering in terms of their social contexts. And that’s the perspective this book is written from—looking at my life and Alice’s, and expanding outward.

A tremendous amount of research went into the writing of this book, so that was just ongoing. I love research. Love. It. But a researched book takes a long time to write.

I did a lot of reaching out to friends with various forms of expertise, especially science stuff, to make sure I was understanding and writing things accurately. And then when the book was done I reached out to some strangers with expertise in various subjects to fact-check myself. It’s so easy how what seems like a small change of wording can make something inaccurate.

In 2015, when I still wasn’t even halfway finished, I actually let myself consider giving up the book. I was just so discouraged. I didn’t know how I would ever finish. It felt like an albatross around my neck. I just wanted to write essays. But I’d put so much time into it, and I thought what I had was good, and the message important, so I decided instead to try reaching out for support from grants and residencies. When I got my first grant—$1000 from the Money for Women/Barbara Deming Memorial Fund—and then my first residency acceptance, from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, I felt like people were telling me my book was important and supporting me to keep at it. And so I did.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I can’t remember, now, where I read or heard it, but Jean Cocteau said, “Listen carefully to first criticisms made of your work. Note just what it is about your work that critics don’t like—then cultivate it. That’s the only part of your work that’s individual and worth keeping.”

I started out as a poet, but when I first tried to write prose in the mid- to late-1980s, I found that I had trouble telling a story with a linear narrative thread. I felt like all my stories failed because I couldn’t do that. Also, all of my “fiction” was completely true. I didn’t have the imagination to make things up.

I wasn’t able to write for a long time due to my illness and the depression that went with it, but when I returned to writing it seemed that the whole landscape had changed. For one thing, there was a whole new category of writing called creative nonfiction. And then I discovered the lyric essay and learned that I didn’t have to write linear narrative. And that freed me up so much.