This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jonathan Escoffery, whose debut story collection is out today from MCD. In these linked narratives, readers follow the multigenerational saga of a Jamaican family in Miami. Having fled their island homeland amid political unrest in the 1970s, Topper and Sanya and their two sons—Trelawny and Delano– struggle to achieve a version of the American dream. Trelawny, born in the United States, finds himself caught between two cultures as he grows up in the 1980s, loving his parents yet feeling ashamed by all that sets them apart—their accents, cuisine, and attitudes—as he internalizes harmful school lessons implying all nations beyond the United States, “seldom mentioned in school, are inferior.” Family members, including cousin Cukie, do their best to make a go of it. Buffeted by racism and financial precarity worsened by environmental and economic disasters, including Hurricane Andrew and the 2008 financial crisis, family members lose their footing. Navigating homelessness, estrangement from relationships, and the alienation that can come from being an immigrant, Trelawny and his loved ones keep moving ahead, managing to find humor and beauty within the sometimes bleak circumstances. Publishers Weekly calls If I Survive You a “vibrant and varied debut.... This charged work keeps a tight hold on the reader.” Jonathan Escoffery is the winner of the Paris Review’s 2020 Plimpton Prize for Fiction and is the recipient of a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship. He is a 2021–2023 Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

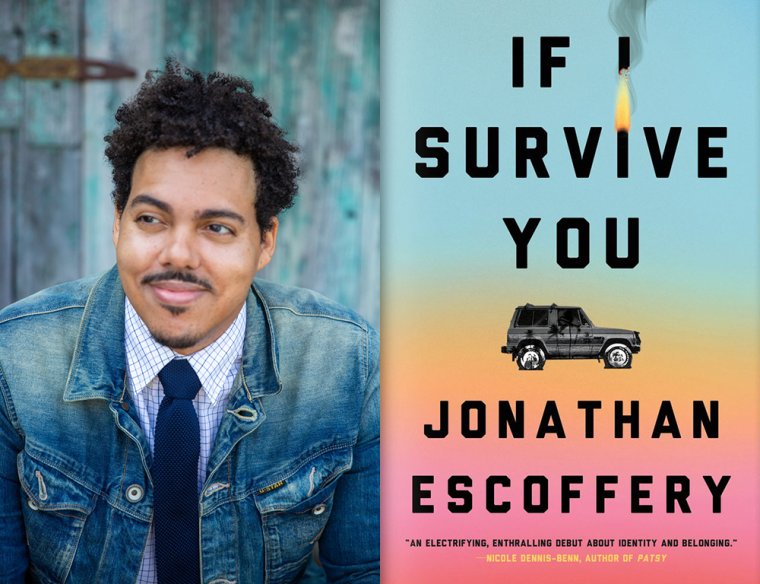

Jonathan Escoffery, author of If I Survive You. (Credit: Cola Greenhill-Casados)

1. How long did it take you to write If I Survive You?

I first began writing about the family that features in If I Survive You a couple of weeks before I turned thirty. I remember the precise timing because I was preparing to apply to MFA programs and this story poured out of me two weeks before my first application deadline. It’s the only story I’ve ever written in one sitting. When I showed it to my two closest writer friends, they said they thought I had something special, which I now interpret as “something a good deal better than what you’ve been writing.” I’d planned to use a different combination of stories for my writing sample, but made the switch.

I sold the book a few months after I turned forty, so I tend to think of it as having taken ten years—all of my thirties. There were seasons of intense writing and seasons in which not much writing happened at all. That first story didn’t survive the revision process, but it was the catalyst for the book, and bits and pieces of it are still alive in some of the other stories in the collection.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most difficult thing was figuring out how to tell the larger story of this Jamaican family that is struggling to survive in America, financially and spiritually, with minimum redundancy across standalone, yet linked, stories. I basically needed to figure out how linked was too linked or not linked enough. It was a real puzzle. I’d recommend to any writer trying this to just go ahead and be redundant and accept that an agent or editor will help you fine-tune this aspect of the book later.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

My most fruitful writing routine—and the one I’ve been most successful keeping—involves going straight from bed to my desk every morning, as soon as possible after I wake up, and continuing a draft of something I’ve already started working on or else revising. This routine grounds my writing life and my life in general. I’m a happier, better-functioning human when I stick to this.

This doesn’t mean I actually write fiction every day. I go through seasons in which I’m more focused on other parts of my writing career, although usually I’m fighting to get back to that routine. It can be difficult to find my way back to it any time I’m knocked off course.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’ve been reading a lot of advance reader copies these days. I just finished Mai Nardone’s forthcoming debut, Welcome Me to the Kingdom, which was excellent and right up my alley as a collection of linked stories that also works as a novel; it’s about people primarily in Bangkok trying to contend with the constraints of class, race, and the remnants of imperialism. And I’ve just started Desmond Hall’s second novel, Barrel Girl.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

I could name a lot of people here, and have in other interviews, but Nella Larsen’s novel Quicksand was probably the most influential work in terms of my striving to write with nuance and bravery about a racialized existence. Reading Quicksand reignited my certainty that I would one day publish a book of my own.

I’ve noticed that when I include women writers as influences—if I mention Mary Gaitskill or Sandra Cisneros or Jennine Capó Crucet, for example—men and women in the publishing business tend to roll their eyes, then ask me about whichever male author they’ve decided I should have said. It’s a strange phenomenon that I haven’t quite wrapped my head around, except to think that people like to ask you questions when they already have their minds made up about what your answer should be.

6. How did your time in an MFA program contribute to the writing and publication of this book?

The best thing my MFA did for me was introduce me to the world of contemporary literature. I wasn’t well read before attending my MFA. I still may not be, but I understand the landscape much better now. It’s vital to know what’s possible in fiction, especially if you’re going to endeavor to further expand those possibilities.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

This is more about the revision process: I didn’t realize people would latch onto the family aspect in my stories and want me to continue following that thread until my agent, Renée Zuckerbrot, pointed it out. Initially I was more focused on the trials and tribulations of the family’s younger son, Trelawny.

Also, prior to speaking to dozens of industry people in the lead-up to my book sale, I wasn’t aware that there’s apparently a difference between fine writing and good storytelling and that the two don’t meet as often as you might think. Industry people will be very impressed if you manage to write a book that exhibits both.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started If I Survive You, what would you say?

If I’d known how long this book—or the writing of any book—would take me, I’d have thrown myself off a bridge. In some ways, it’s necessary to not know and let your optimism and faith take you where it takes you. At the same time, what I might tell myself is that the rejections, the subsequent revision work that makes the writing undeniable, the perspective you gain from taking time with the work, and the life that happens in the meanwhile is exactly what’s going to forge the book into something special.

Another way to say this is trust the process. And try not to beat yourself up about not publishing sooner.

9. What have you learned about the publishing industry that you wish you’d known before you published this book?

If there’s any advantage that story writers have it’s that we can build a track record and a bit of a name for ourselves by publishing somewhat consistently in literary journals and potentially winning awards and prizes before we have a book—and when that happens, agents, editors, and publishers will come looking for us. So maybe I wouldn’t have despaired every time I said I was working on a collection and someone responded, “Stories? But what about a novel?” I’d have also understood that the long journey was going to set me up for a phenomenal reception from the publishing world.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My first writing professor, John Dufresne, gave all of his students this advice, which has aged well with me: Better done than good. Which I take to apply specifically to first drafts. In my younger days, I hated revision and turned a corner in my writing life when I realized that revision is everything. Revision is not just where you make it good, revision is where you figure out what it is. A terrible draft of a story is a gift, because now the real work can begin. But you can’t revise nothing.