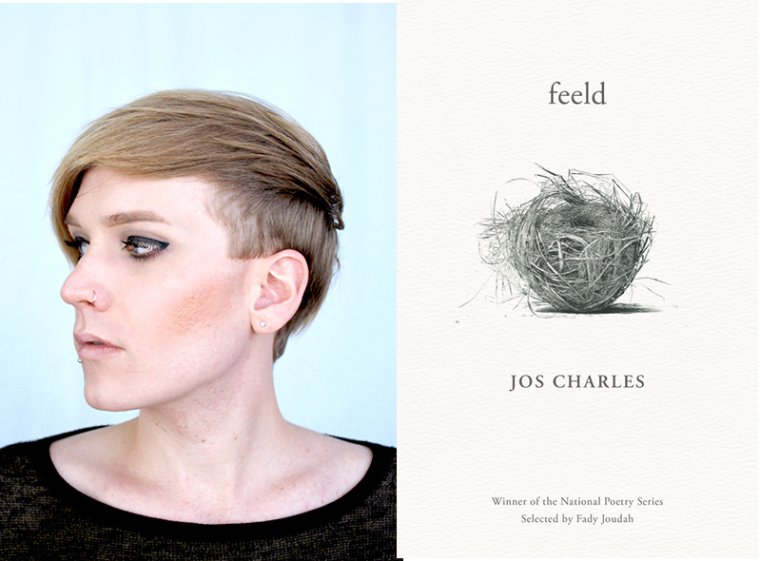

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jos Charles, whose new poetry collection, feeld, is out today from Milkweed Editions. Charles’s second book is a lyrical unraveling of the circuitry of gender and speech. In an inventive transliteration of the English language that is uniquely her own—like Chaucer for the twenty-first century: “gendre is not the tran organe / gendre is yes a hemorage,” she writes—Charles reclaims the language of the past to write about trans experience. “Jos Charles rearranges the alphabet to survive its ferocity against her body,” writes Fady Joudah, who selected the collection as a winner of the National Poetry Series. “Where language is weaponized, feeld is a whistleblower, a reclamation of art’s domain.” Charles is the author of a previous poetry collection, Safe Space, published by Ahsahta Press in 2016, and is the recipient of a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship and a Monique Wittig Writer’s Scholarship. She received an MFA from the University of Arizona and lives in Long Beach, California.

Jos Charles, author of feeld.

(Credit: Cybele Knowles)1. How long did it take you to write the poems in your new book?

I began writing many of the poems in feeld in 2014; I had a compiled set of them in 2016 and completed the edited, to-be-published version in 2017.

2. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When writing the poems that make up Safe Space, I was working retail and then an office job. So I would spend, on a productive weekday, one to two hours writing and editing and about two to three hours a day reading, researching, and taking notes. Weekends I was more intensive. With feeld, I was writing during an MFA program, which meant time was a little less discrete. I wrote an hour or two a day, edited for about two hours a day, and spent four or so hours reading and taking notes. I’ve maintained something close to that now. That said, there can be weeks I don’t write and weeks where I’m writing much more. I write at my laptop, phone, or in a notebook, and just about anywhere.

3. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

The most unexpected thing is how people have found uses to my work. I say this not to self-negate, but to communicate the surprise, the praise, of people coming to find, leave, return to art.

4. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

If you can get into a funded program, yes—it is better pay, hours, and easier than working retail. If you can afford to pay for an MFA, it seems you have access to most resources the MFA provides and your money would be better spent elsewhere—like paying for someone else to get an MFA. It seems to me not worth going in debt over.

5. What are you reading right now?

I recently reread Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and manuel arturo abreu’s transtrender, both of which are beautiful works. I recently subscribed to the Trans Women Writers Collective, which sends out a booklet of writing by a different trans woman writer each month. If you’re able, you ought to sign up for it.

6. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

I frequently have been finding myself recommending Eduoárd Glissant’s poetry. Le Sel noir is a particularly astounding work.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

Its problems are many and the same as the problems most everywhere else, just articulated in a “literary” way. I would, ideally, want the conditions that give rise to all these problems to be fundamentally removed. This would include “big” things like the United States government as it exists, has existed; profit, private ownership of public goods and labor. The old socialist hopes. It would also include those “smaller” things like behaviors and words and presumptions. In lieu of this, if not this, until this, I could see, as a kind of coping with these conditions, an extramarket or extragovernmental body that organizes material support for writers. A public fund where writers get together and try to decide what to do with the pharmaceutical, supermarket, and other such kinds of money that somehow found its way—through tax write offs, donations—to “the writing community,” to be distributed to the most vulnerable within that community. Of course, violences are not equal, so there would need to be some sort of weighted system to determine distribution of funds based on “quantifying” larger social exclusions. I imagine there’d be fewer prizes and grants and more public goods and services—like housing for writers without fixed addresses or legal support for incarcerated writers, online or mailed lending libraries. This would require middle-class, largely academic-situated writers to forgo their grants and, many having faced financial and housing instability before, unfortunately, to become adjacent to those horrors again. That’s what is at stake though. It’s a messy thought for a messy time.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I can’t think of any impediments unique to my writing life, only impediments that are obvious, manifold, to life in general that happen to additionally hinder my writing life: money, other people, myself.

9. What’s one thing you hope to accomplish that you haven’t yet?

I would like to one day run a local, worker’s paper. It would include creative work, organizational events, opinion pieces, and lots of collectivizing of labor, goods. It would also inevitably be time-consuming and a financial failure.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Saeed Jones once said—and I may very well be misquoting—poets don’t make money. If they have money, it came from somewhere that wasn’t, at least initially, directly their writing. Maybe support from parents, another job, or, if lucky, eventually and in addition, a grant here and there, an academic or nonprofit job. As someone who had been writing and publishing for close to ten years before making any money off of my writing, and then certainly not enough to sustain myself, it was good to hear at that time. Which is to say, in a system that doesn’t value writing, but only the marketing possibility of the writer and the written object, to write is the “success” itself. It’s both disheartening and astonishing. So you make a market of yourself and keep what you can off the books. Along the axes of familiar identarian violences, this is typical: You cross the street to walk over there, you shut up there to speak over here, you sell your wares to buy some shoes—and if not shoes, a coke; if not a coke, a book; if not a book, a bag of rice. And what isn’t your wares?