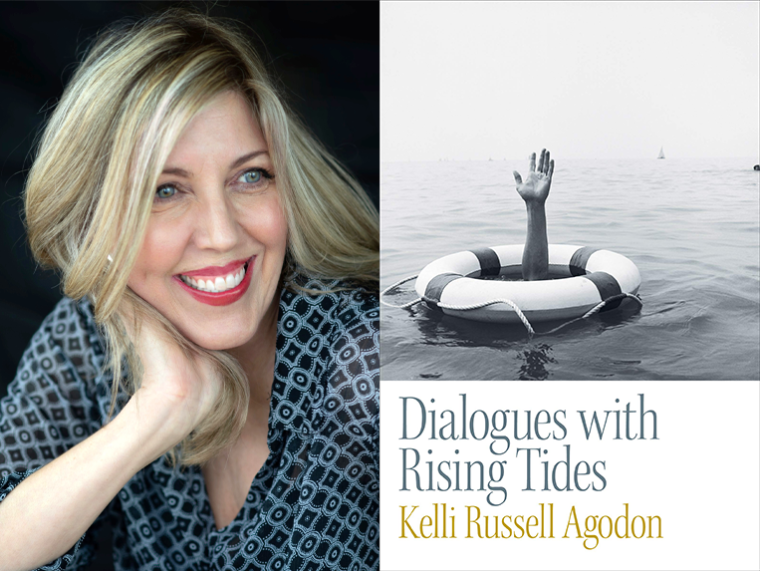

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kelli Russell Agodon, whose latest poetry collection, Dialogues with Rising Tides, is out today from Copper Canyon Press. From the first line of Dialogues with Rising Tides, Agodon is transparent about hardship, yet optimistic: “If we never have enough love,” she writes, “we have more than most.” Instead of seeking to outpace anxiety and fear, she lingers with her most difficult emotions in order to better understand them. She wrestles with both personal and global traumas, setting poems about her family history of suicide alongside those addressing climate disaster. She does not promise recovery, but she does offer pockets of hope—moments of wit and humor that inflect the darkness. “This is the book I need right here, right now, as the fires burn and the tides rise,” writes Diane Seuss. Kelli Russell Agodon is a poet, writer, and editor from the Pacific Northwest. She is the author of three previous poetry collections, including Hourglass Museum (White Pine Press, 2014). She is the cofounder of Two Sylvias Press and the codirector of Poets on the Coast, a writing retreat for women. She also teaches at the Rainier Writing Workshop, a low-residency MFA program at Pacific Lutheran University.

Kelli Russell Agodon, author of Dialogues with Rising Tides. (Credit: Ronda Piszk Broatch)

1. How long did it take you to write Dialogues with Rising Tides?

I wrote “Braided Between the Broken” and “Love Waltz with Fireworks” in December 2013 and January 2014 respectively. At the time I didn’t realize I was beginning a new manuscript, but those two poems make up the right and left ventricles of the collection—one acknowledges a flawed self while the other tries to fall in love with a flawed world. I hadn’t realized I had started a new book until 2015 when I created the I-think-I-may-have-a-new-book-in-the-works folder called, uninterestingly enough, “Manuscript 4.” Dialogues with Rising Tides was accepted by Copper Canyon Press in March 2019 and I turned in my final version on Valentine’s Day 2020, so final answer: five to six years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Amusingly enough, I’d say trying to answer this question. Finding the best order for the poems is always a bit of a task, deciding whether to take a poem out or put one in can be a challenge, but mostly I so enjoy the process of creating a book that there isn’t one particular aspect that comes to mind. I guess if writing a book was a map, I’d say choosing which road to follow is probably the hardest part, as there are so many journeys I’d like to take.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I tend to be a seasonal writer—I write much more from September through May and easily kick into that school-year schedule. However, during the pandemic, fellow poets Martha Silano, Ronda Broatch, and I started what we now call “The Thursday Night Poetry Club,” where we show up with quirky writing exercises and write on Zoom from 5 to 7 PM.

I refer to them as “quirky writing exercises” because we add some curious elements, such as blocks of random words, unexpected questions—Does rain ever tumble into a lightbulb? Who plugs in the weather?—and maybe a few instructions: Describe a ghost’s fedora. We do three prompts for about eighteen to twenty minutes each and share our work.

I also did some collaborative writing with Melissa Studdard, Jeannine Hall Gailey, Dean Rader, and still have many online writing dates with my friend Susan Rich. They have all helped me get through the pandemic and continue writing poems.

As to where I write—I pulled the lawnmower out of our shed during the pandemic, added a desk and a chair, and turned it into my writing space. There were just too many people home during the pandemic and I was struggling to write with all that energy around me and so many dirty dishes in the house. Oddly, the dirty dishes were still there when I returned from my writing, but at least I wrote.

4. What are you reading right now?

Besides e-mail? I love nonfiction and am reading Useful Delusions: The Power and Paradox of the Self-Deceiving Brain by Shankar Vedantam and Bill Mesler, which is a fascinating look at how the mind uses self-deception as a way to create happiness. Also: Night Angler, a stunning collection of poems on family and fatherhood by Geffrey Davis. When I read Davis’s poems I feel as if I am being held in a deep prayer—the writing is beautiful and meditative. It’s a book I keep returning to. I also recently realized some of my favorite poetry books are available as audiobooks, so I’m listening to Jericho Brown’s The Tradition, Paige Lewis’s Space Struck, as well as Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights and Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Sandra Yannone, January Gill O’Neil, and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha are three of my favorite poets and people whom I’d love to see get more attention for their work. But also, nonbinary, trans, and queer writers, as well as most women authors over the age of sixty and writers who have books from smaller indie publishers. I think there is always room in the literary community for more recognition. Poets tend be like meteor showers: They are acknowledged when they are seen, but many times, the world is looking in another direction and misses the show completely.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Besides sunny days, I would say my ability to put nonessential work before my writing. Also, snacking.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

As the newest faculty member of the Rainier Writing Workshop—Pacific Lutheran University’s low-residency MFA program—and a graduate of the program myself, I’d love to give a big “yes” here.

For me, returning to school to get my MFA was life-changing, as it created the space and time I needed to write and taught me how to be an advocate for my writing life; it made me take my work more seriously. I still have that community and I look back on my days at PLU as some of the happiest times in my life. Our writing lives are such a personal choice—each person needs to determine what their writing life needs. Returning to graduate school made me a stronger poet and led to my book, Letters from the Emily Dickinson Room, which was my creative thesis at PLU. An MFA definitely gives writers the structure and accountability they may be lacking in their own lives.

8. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Dialogues with Rising Tides?

Vintage photographs of lightships and lightvessels whose names became my section titles—Breaksea, Cross Rip, Overfalls, Black Deep, Shambles, Scarweather, and Relief—but also old maps, a misremembered quote from Zelda Fitzgerald, a line from an Anne Sexton poem, and a quote from Postcards From the Edge by Carrie Fisher. But I’d say the central form of work was the natural world—the sea and the landscape of the Pacific Northwest. Nature will always be the top source in my bibliography.

9. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

Anything and everything. When I’m working on a book, I’m in my happy place. But I also adore the “almost done” place. Right before I’m ready to turn in the final version, decisions feel big—what to leave in and take out, final word/image choices, and so on. There is this moment when my intuition comes into play. I’m very much a trust-my-gut person, and when I’m in this space, I have an inner knowing about what works. It’s like looking at the insides of a pocket watch and seeing all the parts moving, and while I may not understand how everything came together, I can see it’s ticking and complete. I miss that breathless moment of knowing it’s done and the confidence of that space, which I lose the moment the manuscript is out of my hands.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The best advice I hold onto that works for both one’s writing life and daily life comes from drag queen Alyssa Edwards: Don’t get bitter, just get better. In regards to submitting one’s work, poet Elizabeth Austen said these wise words: Don’t say no for them. It’s their job to say no, not yours. Meaning: Don’t self-select yourself out of opportunities.