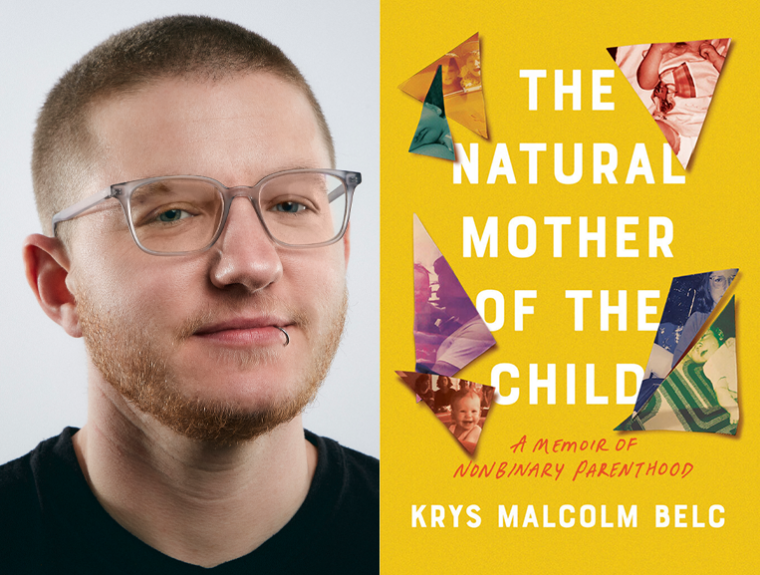

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Krys Malcolm Belc, whose debut, The Natural Mother of the Child: A Memoir of Nonbinary Parenthood, is out today from Counterpoint. In The Natural Mother of the Child, Belc weaves back and forth in time to tell the story of his life as a nonbinary, transmasculine person and parent. He focuses particularly on his experience carrying and birthing his son Samson: “Queer people had children,” he writes, “but I almost never saw pregnant people like me.” Raising Samson and his other two children alongside his partner, Anna, Belc finds clarity about his gender and past. He also speaks candidly to the inevitable moments of shame, jealousy, and anger that populate a life, including those particular to life as a parent. Accompanied by ultrasound images, family photos, and other documents, The Natural Mother of the Child is an intimate and inventive text about transness, family, and caregiving. Krys Malcolm Belc is also the author of the flash nonfiction chapbook In Transit (The Cupboard Pamphlet, 2018). His work can be found in Black Warrior Review, Granta, and the Rumpus, among other publications. He holds a BA from Swarthmore College, an MEd in special education from Arcadia University, and an MFA from Northern Michigan University. Belc lives in Philadelphia.

Krys Malcolm Belc, author of The Natural Mother of the Child: A Memoir of Nonbinary Parenthood. (Credit: Mark Likosky)

1. How long did it take you to write The Natural Mother of the Child?

About two and a half years of really focused work to have a solid draft. I wrote the majority of it in an MFA program that I started just a few months after my third kid was born. I went to school for fiction and this book happened instead. The book sold soon after I started working as an educator in a pediatric oncology clinic, and so I was editing it while learning so much about cancer and its impact on patients’ school functioning. Instead of feeling like my book was frivolous or navel-gazing, I found great solace and gratitude in getting this story right and in getting to think deeply about myself again at the end of a long day.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It’s very hard to maintain the clarity of sentences, moments, and scenes in writing that is ultimately about ambivalence and in-betweenness.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I don’t write more than once a week. Daily writing is just not a thing that leads to good art for me. Given how people talk about productivity and writing, it is hard to accept my own pace, but I’m getting there. I can’t do anything in twenty minutes or even an hour. The idea of a daily word count horrifies me. But every day I do try to write a little prompt in a document or notes app, so that I have a variety of possible starting points when I have time to sit down. Even just a phrase. Yesterday’s was “Strawberries, again.”

4. What are you reading right now?

I am reading White Girls by Hilton Als and I am listening to Tana French’s The Likeness. On deck is Chase Burke’s chapbook Men You Don’t Know You Know.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Lori Ostlund’s debut short story collection, The Bigness of the World, absolutely changed my life. Not my writing, my life. When I encountered it I had recently moved to the Upper Midwest to give my writing life more dedication and intention, and her characters move in reverse, out of the Midwest. That book helped me to adjust to living in a place that I was unprepared, on the deepest level, to love, and in the end I did love it and still do. If you know, you know; a lot of queer writers in my life know and admire her work. Its emotional precision is unparalleled. Everyone should read it and her pitch-perfect novel, After the Parade.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I wish we could do away with the idea that telling the story of a life in temporal order within the confines of a narrative arc is the “natural” way for memoir to be. It impedes my confidence and imagination, worrying what a market might make of what I create. I don’t want it to, but it does. These confines are a barrier to many marginalized stories even making it into the world. Life is messy and some of us want to corral it into a recognizable form, but others want to embrace the questions and fracturing and employ forms that are in the service of that messiness. If we’re going to ask me why my work is in the form it’s in, why don’t we ask every single memoirist that? All memoirists are making art out of time, and there isn’t one way.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

My agent, Ashley Lopez, has an absolutely incredible editorial eye. Her comments on my manuscript, when I finally had one, led to some of the best writing of my life, sections that are now some of my favorites in the book. She and my editor, Jenny Alton, did not try to morph my work into something it isn’t. It has an unusual form and many images, and they did what they needed to do to help me sharpen my vision and my sentences without telling me to have a different imagination than the one I have.

8. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I show my partner, Anna, everything I write that I think even has a spark of hope in it. My book has many sections of direct address to her because the most complex thoughts and feelings in my life sometimes only come into sharp focus when I imagine myself explaining them to her.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Before I went to graduate school for writing, I read books because they were best-sellers, “classics,” in the Best American series, and so on. Turns out, this isn’t because I have a small appetite for experimentation or a limited imagination. But how was I supposed to find books to read? I was an elementary school teacher living in a neighborhood with no independent bookstore—though we now have two, Harriett’s Bookshop and The Head & The Hand. I didn’t know writers would come hang out on Twitter. I had never seen a chapbook. There has to be a way to make sure that work that isn’t a blockbuster finds its way to people who don’t have the time to be full-time book sleuths. All kinds of readers deserve to find small press books. The deck is stacked against readers and writers who aren’t in academia finding brilliant books that bend and break boundaries.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Monica McFawn told me to think about my writing when I was doing other things and to “count” that as writing time. There’s a lot happening in my life now more than ever. Monica’s advice years ago was a gift that has allowed me to feel like I am truly a writer even though I must engage in paid work and care work during many of the hours and days I’d like to have time to make art.