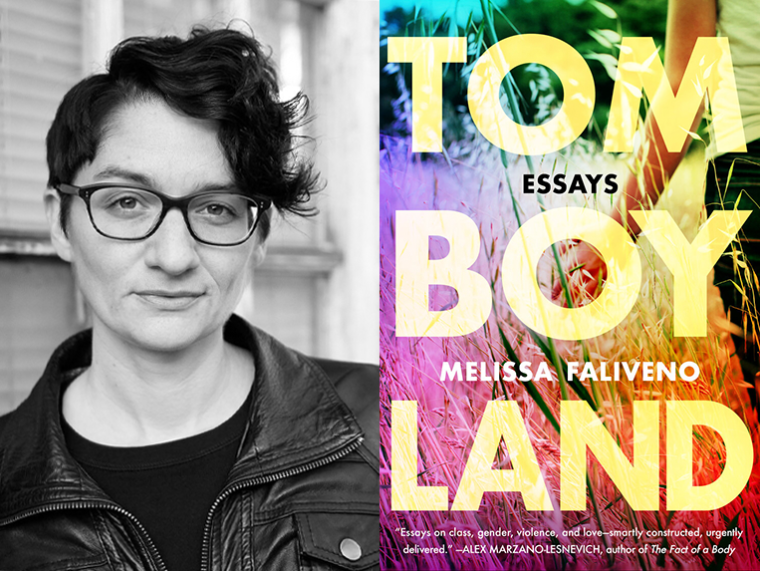

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Melissa Faliveno, whose debut essay collection, Tomboyland, is out today from Topple Books. Tomboyland opens with a vignette from 1984, when the largest tornado in Wisconsin’s history destroyed a small town only eight miles west of Faliveno’s childhood home. “Maybe the wind was howling. Maybe there was thunder,” she writes. “Maybe, more likely, there was only silence—that still, strange calm Midwesterners know so well, the kind that heralds the most violent of storms.” No matter her subject, Faliveno conjures each scene with similarly precise language. Drawing on both personal memory and thoughtful reportage, she roams from the site of disaster to softball fields to meditations on gender and family. She is also always more than one thing: a Wisconsinite, for instance, but also a New Yorker—one of those “city slickers who ask a lot of questions.” Tomboyland is a book of the questions that arise from living in various in-betweens and Faliveno models how to thrive in the mystery. “I didn’t just read Tomboyland, I scribbled in its pages, photographed its passages, pressed it on friends, and felt an urgent need to talk about it,” writes Alex Marzano-Lesnevich. Melissa Faliveno previously served as the senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine. Her work has appeared in various publications, including Prairie Schooner, DIAGRAM, and Green Mountains Review. She received her MFA in nonfiction writing from Sarah Lawrence College, where she currently teaches in the graduate writing program.

Melissa Faliveno, author of Tomboyland. (Credit: Maggie Walsh)

1. How long did it take you to write Tomboyland?

Oh man, a very long time! I’ve been working on this book, in fits and starts, for about ten years. I wrote the oldest essay in the collection, “Of a Moth,” in 2010, when I was a graduate student. (My teacher and one of my advisors, Vijay Seshadri, gently eviscerated the first draft, telling me I needed to read more deeply about moths; it was great and necessary advice.) Between then and now I’ve been slowly chipping away at these essays. Some I’ve revised again and again, picked at, gutted and remade. I wrote the newer essays a little more quickly—and by that I mean a year or two, rather than ten. Although, the near-title essay, “Tomboy,” came in something of a torrent in 2017, after the election. It was something I needed to get out of me, these big hazy questions about womanhood and queerness and class and the body and the lands we come from and inhabit and leave—and how it all shapes and complicates our identities. That’s the piece that got the attention of my agent, and really kicked the book into gear. Between then, in early 2018, and when I finished the book, in the summer of 2019, it all went pretty fast. But mostly I’m a long-game writer, and it takes me forever to be satisfied with something. And even then I’m never actually satisfied. I just hit a deadline, or someone takes the proverbial red pencil out of my hand and says, “Okay, M, that’s enough now.”

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Whew—all of it? Just kidding. Kind of. I spent so many years thinking I would never actually make it here, to seeing these essays published in a book. I got rejected a lot, but more often than not I was my own worst enemy in terms of belief in my work. I was usually convinced that being an author just wasn’t in the cards for me. Sometimes I got very close to quitting—and there were long stretches of weeks, and months, when I didn’t write at all—but I always eventually went back to it. I realized at some point that I couldn’t stop writing even if I wanted to, even if these essays were just for me. So, in a sense, those long years of writing alone, of never quite believing in myself or my work, was the hardest part.

But in terms of the writing process itself, I ended up exploring some pretty difficult stories and experiences in this book—some of which belonged to other people, some of whom hadn’t told those stories aloud before, and they were giving them to me to hear, and then hold, and then write down. That’s a huge responsibility and hard work—to take the best possible care of people and the stories they give you so that you, in turn, can give them away again. I also interrogated a lot of very personal questions and experiences of my own—many of which I had done a prime Midwestern job of repressing for a very long time. It was difficult to put myself back in those places, to confront those questions and truths about myself and my life, the stories I grew up believing and eventually began telling myself. What results from that interrogation are some pretty personal revelations—a few of which people close to me never knew before reading this book—and that’s a pretty terrifying and vulnerable feeling. It’s also pretty liberating.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

This has changed a lot in the past year, since finishing this book. For about fifteen years (including nearly eight of them when I was an editor for this very excellent publication—I miss you guys!) I almost always worked 9-to-5 jobs, which of course are never actually 9 to 5. I snuck in writing time when I could, in the wee hours of morning, nights and weekends, whenever I could get away for a few days. Since finishing this book, I’ve had the good fortune of being able to restructure my life as a writer and a teacher. I write every weekday now, usually in the morning, after a cup of coffee and a chapter or two of reading. Regardless of what I have to do that day, I always try to get in at least an hour or two of writing—or revising, or editing, or whatever project I’m working on. I’m a creature of habit and routine, so that structure really helps me keep going. I often give myself weekends off, but I still write if and when the iron is hot. And the more regularly I write, it turns out, the hotter the iron stays.

I have a little office in my apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, with red walls and several overflowing bookshelves and a few plants and a couple guitars on the wall, and my writing desk is nestled in tight between the dog crate and the litter box. It’s a hot, smelly little room, but it’s a room of my own.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Kiese Laymon’s memoir, Heavy, which is devastatingly good. I’ll be thinking about it for a long time. And I’m currently reading Genevieve Hudson’s debut novel, Boys of Alabama, which is hitting some very good spots for me—masculinity, ruralness, religion and cults, small-town football, queerness, class. Basically everything I want in a book all the time.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Oh, so many. But one I will shout from the mountaintops forever is Joni Tevis, whose essays are truly extraordinary works of nature and beauty and music and love and, always, exploration—the best thing an essay can be. Joni is also just the kindest and most generous human on the planet, and everyone should know her and her work. Start with The World Is on Fire: Scrap, Treasure, and Songs of Apocalypse. It’s, you know, pretty timely.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Money and time, which of course are related. And by “related” I mean a vicious and unrelenting cycle of work and stress and anxiety and despair built and perpetuated by capitalism!

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I think it’s pretty clear that the entire system is due for a serious reckoning. It’s well past time for institutions and publishers to take some real action—beyond statements of allyship, and even beyond publishing more work by people of color, queer and trans people, working-class people. We need to be making space for marginalized people to hold positions of power. This might mean actual sacrifice, and it might be pretty uncomfortable for people who have been very comfortable for a long time. This industry can’t claim to be “diverse” while relegating marginalized people to low- and mid-level positions wherein they have no actual autonomy, they’re living paycheck to paycheck, and they can’t stand up for what they need or believe without fear of losing their jobs. There’s no real change if we’re sticking to the same old game, with straight white men and women at the top, and young, underpaid, marginalized, and strategically silenced people grasping toward some semblance of stability beneath them. I’m hopeful that some things are starting to shift. But we need a sea change, not just a tide that swells every so often and then recedes again. Also: We really need to pay writers better for their work. See question six.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Tomboyland, what would you say?

Trust yourself. Stop trying to please so many people, especially those who don’t actually care about you and your work. Keep seeking those who do. They’re out there. You have something to say, and it has value. People will say no, but keep going anyway. You’ll finish a book someday. And then it will be published! I know this sounds like an impossible lie! I promise you, it’s not.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My good friend, the brilliant essayist Melissa Febos. She was the first reader of Tomboyland in manuscript form, and I trust her wholly. Not just because she’s a friend who won’t bullshit me, but because she’s a writer whose work I deeply respect, admire, and connect with. She tells me when something’s working and when it’s not. She asks questions and suggests ideas for getting through something that’s tripping me up. When I’m freaking out, which happens regularly, she talks me off the ledge. She also reminds me to celebrate when it’s time to celebrate—something I’ve never been good at—and sometimes she’ll even bring me a cupcake. Every writer needs a Melissa Febos in their life. (Thanks, Mitch.)

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My former graduate thesis advisor and longtime mentor/essayistic magnetic north, Jo Ann Beard, recently said this: “You always feel better when you’ve done your work. So do your work.” Also, someone else said this, and I wish I remember who said it, but it stuck with me: “Writing is hard. If someone tells you it’s not, they probably aren’t a writer.”