This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, whose debut poetry collection, The Life Assignment, is out today from Four Way Books. Writing in both English and Spanish, Maldonado roams from Puerto Rico to New York City while navigating questions of home, family, and belonging. At times the narrator cannot find peace in his own body—“mad to be in my flesh for one last / minute,” he writes—yet the speaker always presses forward, finding multiple pathways, and embracing a full spectrum of emotions, from love to rage. Revisiting, revising, and playing with memories and moments, Maldonado offers a model for a polyphonic existence. “The poems in The Life Assignment dare to rest in the discomfort of displacement—of the self, of the heart, of literal location,” writes Lynn Melnick. “I don’t think I’ve read a book like this before.” Ricardo Alberto Maldonado is a poet and translator from Puerto Rico. He is the translator of Dinapiera Di Donato’s Colaterales/Collateral (Akashic Books, 2013) and has received fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Queer/Arts/Mentorship, and CantoMundo. He lives in New York City, where he serves the managing director at the 92nd Street Y Unterberg Poetry Center.

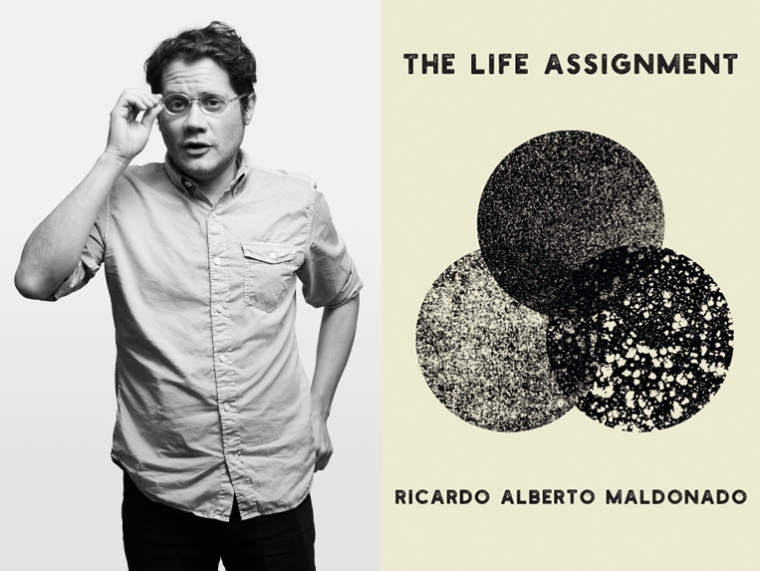

Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, author of The Life Assignment. (Credit: Eric McNatt)

1. How long did it take you to write The Life Assignment?

Ten years. More? The bulk of it: on and off for a decade. The fifteen or so poems in both Spanish and English were written after María made landfall in Puerto Rico. The heart of the book, as I see it: close to three years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Knowing that I could see myself and whom I love, my country, as being legible to the poem, a poem, my poem, even to myself—I had to learn how to do that. Learn the labor of seeing when one is looking that way: toward the homeland. A line from García Lorca’s “The Child Stanton” comes to mind as I try to answer this question: “vete...para que aprendas, hijo, lo que tu pueblo olvida.” Greg Simon and Steven F. White translate this as: “Go to learn, my son, what your people forget.” Who can I call my people? What do they forget, how can I learn and relearn it, and why?

I want to see in my book something I have to affirm—something I am more interested in thinking and talking about: If a (any) narrative arc is worthy of our consideration, it is that the book serves as an act of reconciliation between the body in/of the city and my home language. By which I mean, in the language of the diaspora I could find my assignation.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Often is an uncanny word to think about this year. Where? In the kitchen, between acts, in bed. I have fifteen poems in as many weeks. The apartment is home, therefore: everything. I wrote a poem with words my nephew used on WhatsApp, a poem about insomnia, poem that for lack of effort I titled “For Lack of Effort I Title This Poem New York: April 24.” I told Timothy Donnelly I would title a poem “Dick Loves Me.” Twitter has me writing poems on prescription bottles, poems around the room, poems on graph paper. Poems used to take time to write—but all things I cannot see sing now.

4. What are you reading right now?

Been reading and rereading Svetlana Alexievich for some time now—in print and audio. The world coheres because of her. Other things I’m reading, of equal urgency: I just reread Diana Marie Delgado’s Tracing the Horse and found it extraordinary. I am always reading Gwendolyn Brooks. Always, it seems, for the first time, even when it’s not the first. At the start of the pandemic, the Poetry Project released a reading by Ntozake Shange and Gwendolyn Brooks. Quit this interview and head there for it.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I will celebrate the work of Caribbean and Central American writers—those working in and against vocabularies of empire—including Merle Hodge, Edwidge Danticat, Nicole Cecilia Delgado, Jamaica Kincaid, Yara Liceaga Rojas, Manuel Ramos Otero, Maryam Ivette Parhizkar, Tiphanie Yanique, Esteban Valdés, Camille Rankine, Raquel Salas Rivera, Sheila Maldonado. Some emerging, some not. The list is infinite—may it continue to be.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The fear that I may render in my poem a life—my life—illegible to others and to myself. I’ve been living with a thoracic injury for some time; with bad posture, muscles swell, such that every day I ask myself, What are you to do for words?

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I see them often, publishers of renown, celebrating the symphonic sweep of a welcoming American. Yet in whom they publish, one sees a Republic of Persistent Occupation. One could quote the president: “We speak English here.” Choose the bilingual, the multilingual, and the polyglot. The one who translates for another is beloved.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Life Assignment, what would you say?

This as kindness and mercy: Be with your home language, sooner. There, in that part of your body, is your beginning.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I want my nephews to find affirmation and corroboration in my poems, to discover something about me and themselves. Doesn’t that make them, in theory, my most trusted readers? But to answer: I use voice memos to send a few trusted poets recordings of new work. I write for them, too. Initially.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

When writing a poem, spend good time moving beyond plain structure and plain fact.