This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ryad Girod and Chris Clarke, the author and the translator of the novel Mansour’s Eyes, which is out today from Transit Books. In 2015 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, a young Syrian architect named Mansour al-Jazïri is about to face public execution. As he is led through the crowd to the center of the square, his close friend Hussein looks on in grief, and reflects on the preceding months that led to this moment. Three months ago, Mansour began experiencing increasingly intense headaches, suffering the early effects of a degenerative disease a doctor deemed “irreversible,” but Hussein held out hope: “I felt that, in spite of everything, Mansour sensed things and understood situations,” he writes. “He always returned to me, descending from atop his dune, his eyes always luminous.” While telling his friend’s story, Hussein reflects on the life of Mansour’s great grandfather, the famous Algerian leader Emir Abdelkader, and recalls the execution of another Mansour from history, Sufi mystic Mansur Al-Hallaj. Illuminating and connecting these various pasts, and gradually revealing the full circumstances of Mansour’s misfortune, Mansour’s Eyes is a complex exploration of religion, politics, and history. Mansour’s Eyes is Ryad Girod’s first book to be translated into English. He is also the author of Ravissements and La fin qui nous attend. He lives in Algiers, where he teaches at the Lycée International d’Alger. Chris Clarke has translated numerous French language authors, including Marcel Schwob and Patrick Modiano. He is a PhD candidate in French at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

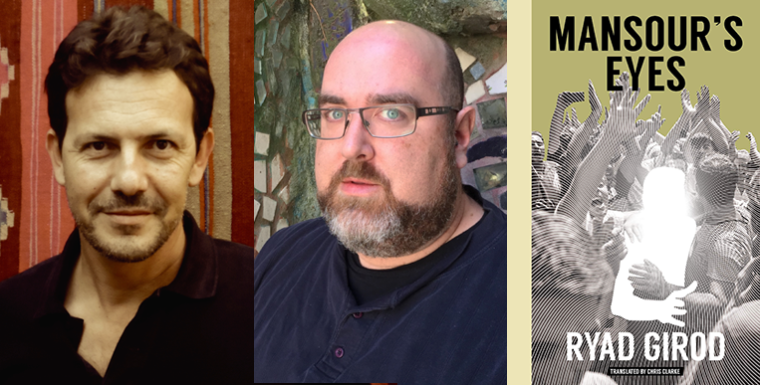

Ryad Girod and Chris Clarke, the author and the translator of Mansour’s Eyes.

1. How long did it take you to complete work on Mansour’s Eyes?

Ryad Girod: The book was written during two different periods. The idea of writing a story set in Saudi Arabia came to me during my final year living in Riyadh. I wrote a few paragraphs over the course of about a month, then I put it aside when my second novel was being released, as I needed to focus on promoting it. I didn’t take up the writing of Mansour’s Eyes again until two years later, and it went quite quickly. It took about eight months.

Chris Clarke: Transit Books had asked for a relatively quick turnaround on the translation, and so I worked on the translation of Mansour’s Eyes every day for the better part of two months last summer. I was also writing my PhD dissertation at the time; to make progress with both, I translated from morning coffee until after lunch, and then shifted gears to my dissertation in the early afternoon. I suppose if I had known at the time that we’d be stuck indoors all spring in 2020, I might not have set things up so that I would end up spending the entire summer of 2019 indoors, parked at the kitchen table. But at the end of the day both projects are completed and I’m happy with how they turned out.

2. What was the most challenging thing about the project?

Ryad Girod: The initial idea was to write a story around the possibility of understanding situations in this modern world through the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. But early on it became clear to me that it wasn’t going to work. And so, more modestly, I instead wrote a story that still dealt with comprehension, but I made sure that it was neither too philosophical nor too superficial. As if I was moving along the line that formed the crest of a dune…

Chris Clarke: My primary challenge was learning how to inhabit Ryad’s syntax. His descriptive passages are very rhythmic and, for me, it was very important to recreate that rhythm. I felt that his sentences, especially when he’s describing the Najd, mimic the shapes of the dunes and cliffs they describe, and it took me some time and a lot of reading aloud to find those crests and valleys. Another interesting problem was how to approach the transliteration of the Arabic names in the text, as the methods in use in French differ from those in use in the Anglophone world. Neither language is very consistent about this, and the options also haven’t remained static over the years. There are political implications to such choices, but I was helped in my decision by some fascinating conversations with a colleague and further talks with Ryad.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write? Where, when, and how often do you translate?

Ryad Girod: I don’t write all that much. But when I get going, I do nothing else. Mostly in the morning, in bed, when I first wake up. Although with Mansour’s Eyes, 80 percent of it was written in my car. In the parking lot of the pool where my daughter Aziadeh had been swimming two hours a day four days a week.

Chris Clarke: It all depends on my deadlines, and on what else I’m working on at the time. But typically, when I have a project underway, every day, most often in the afternoons, and for five or six hours at a time. Much more than that and my work starts to get sloppy and takes twice as long.

4. What are you reading right now?

Ryad Girod: Saint Augustine’s Confessions. An “Algerian” philosopher from the fourth century who wrote in Latin. It’s a work that is both deeply spiritual and very human.

Chris Clarke: I’ve very recently submitted my PhD dissertation to my reading committee, and won’t be starting my next full-length translation until after the defense in about three weeks, so I’ve been relaxing by reading old hard-boiled crime novels. David Goodis, Fredric Brown, Charles Williams, and most recently, Derek Raymond. It’s a lovely breath of fresh air, as I haven’t been able to indulge in such reading for a long time.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ryad Girod: Claude Simon, without any hesitation. For a Nobel Prize winner, he still isn’t a household name, and his body of work, which is incredible, is relatively unknown. In my mind, he’s one of the fathers of the modern novel. For Anglophone readers, he could be compared to Joyce or Faulkner. Also, Marie NDiaye: so understated, a breathtaking stylist.

Chris Clarke: In French, Jacques Jouet comes to mind. I’m really hoping to translate one particular book of his in the coming years—I think he’s very underrated. His work interests me from a formal and constrained-writing perspective, but he’s also just a really good, natural-feeling writer, and very funny. I have also recently enjoyed the Argentine writer Samanta Schweblin’s books, in Megan McDowell’s translations. Her work has been getting some love in indie circles, but I’m surprised she hasn’t caught on in a bigger way. I’ll read anything that pair offers up. As for English-language writers, I’ll need a few months of catch-up time before I have an answer.

6. What is one thing you might change about the literary community or publishing industry?

Ryad Girod: For France, nothing in particular. Algeria needs more bookstores and better distribution.

Chris Clarke: It would be great if more readers purchased literature in translation, and if the major publishers were more open to publishing it. It often seems to me that despite them being the ones with all the capital, they leave it to the independent publishers to find the next great non-Anglophone voice, and then jump in and grab them up after the risk has been absorbed.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Ryad Girod: I have a tendency to write very long paragraphs, sometimes without real syntax or punctuation, something that Selma, my editor, refers to as “monoliths.” As a result, I’ve learned to aerate them.

Chris Clarke: I learned that Transit Books publisher Adam Levy has a pronounced phobia of exclamation points!!!

8. What is the biggest impediment to your creative life?

Ryad Girod: Work! I still have to teach to earn a living… And social media, such a time-eater.

Chris Clarke: The same as most everyone else: time and money. And trying to find some semblance of balance between a productive career and the rest of life.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Ryad Girod: A reader I don’t know, someone totally impartial.

Chris Clarke: My wife Renee, whose insights always brings me back to the bigger picture when I get lost in the details. And my colleague Lara—we trade our finished translations back and forth and offer each other many suggestions and comments. Her comments make me think through my choices in ways I otherwise might not.

10. What’s the best piece of creative advice you’ve ever heard?

Ryad Girod: Listen to music while you write, which is something I do routinely. Classical, jazz, sacred music…

Chris Clarke: I agree with Ryad, I almost always translate with music on. For me, it really needs to be instrumental music so that lyrics don’t get in the way of the voice I’m trying to hear. On a more technical level, I often think back to a comment from Richard Sieburth, who taught me that writers and translators can put too much emphasis on using adjectives and adverbs to punch up their descriptions, when sometimes it can be done better with a well-chosen verb.

Editor’s note: Ryad Girod’s answers appear in translation from the French by Chris Clarke