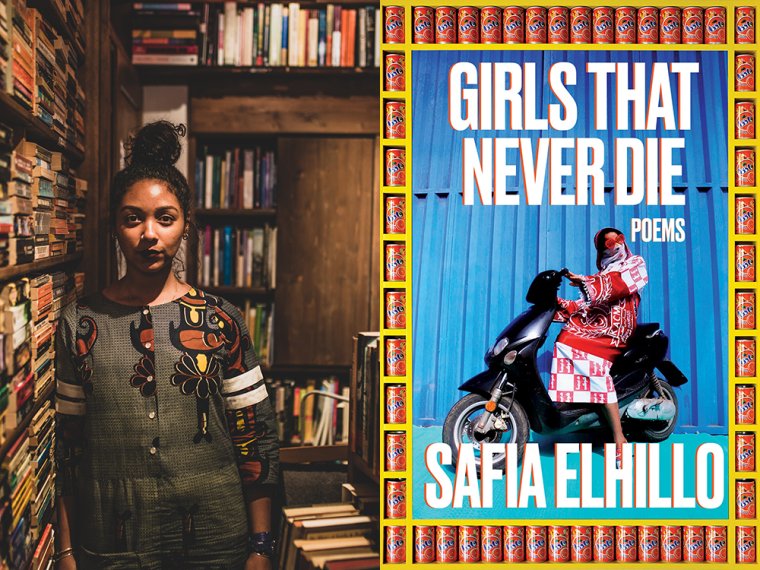

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Safia Elhillo, whose poetry collection Girls That Never Die is out today from One World. In this daring book, Elhillo considers what it means to grow into womanhood while enduring the psychic and physical wounds of partriarchy. Here the Muslim girl becomes a hero figure, navigating a world of narrow expectations, shame, and silence to save an authentic self. Lyrics interrogating family history mingle with those mining Greek myth and current events alongside others that create their own mythology of the “girls that never die.” They are rescued in some poems by magical interlopers and in others by a fierce internal spirit that asks: “But what if I will not die?” Sudanese by way of Washington, D.C., Safia Elhillo is the author of The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), which received the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets and an Arab American Book Award, and the verse novel Home Is Not a Country (Make Me a World, 2021). She has received a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation as well as fellowships from Stanford University and Cave Canem.

Safia Elhillo, author of Girls That Never Die. (Credit: Aris Theotokatos)

1. How long did it take you to write Girls That Never Die?

About five years, though a lot of the early poems didn’t make it into the final version of the book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

This book really fought me, or I fought it, for the first couple of years. I went in with an idea about the book I already wanted it to be, before I’d written it, and tried for years to wrestle the manuscript into the shapes I’d predetermined—and failed spectacularly. There are several versions, a book-length poem, that will never see the light of day. Another challenge was trusting that failure, and believing that the correct version of the book was in there—or out there—somewhere. I had to keep resisting the temptation to stop when it was just okay—or good enough or close enough—to get to the version of the book that I could feel existed somewhere in the murky dark of all this, that I was feeling my way toward. It was a challenge to keep going, especially when several of the discarded drafts really were tempting in how they basically looked like a fully-formed book, behaved like a fully-formed book, but not the one I was actually trying to write. Those drafts were fine—they were okay—which was more frustrating than if they’d just been bad and unusable. I had to ignore that temptation to stop and keep going, several times, until I finally found my way to the book I wanted to write, which ended up looking nothing like the book I thought I’d set out to write.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It depends. I wake up every day wanting to write. And then most days I don’t write. A few times over the past couple of years, I’ve tried to remedy this by doing a 30/30 project, in which you try to write a poem every day for a month, with a friend. When I was younger I could barely get through three days of it, but it’s gotten easier in recent years because I’ve tried to pay attention to the conditions that make me feel best equipped to write poetry. So when I’m doing one of these 30/30 projects, or sitting down to write in general, I’ll read some poetry, look at a list of words I like—things like that—and eventually a draft of a poem will get done. Usually it’s not a great draft. But fear of the bad poem is usually what keeps me from sitting down to write at all, so writing a bad draft one day and then having to come back and sit down and try again the next day is a helpful sort of exposure therapy for me.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Zeina Hashem Beck’s stunning new collection of poems, O. I just finished Elamin Abdelmahmoud’s memoir, Son of Elsewhere: A Memoir in Pieces, and was really moved to be able to spend time with a book by a writer who shares so many of my identity intersections. I also accidentally learned a lot of Sudanese history from it—I love the way it’s folded into the story.

5. How did you know when Girls That Never Die was finished?

It really ended up being about the order. The poems had been done for what felt like a while, but something still didn’t feel quite right. I was so frustrated that I was about to go back into the poems and try revising them again, thinking that’s what the problem was. But it turned out the problem was the order, and it had been for some time.

6. What trait do you most value in your editor?

My editor, Nicole Counts, was so patient with me throughout this whole process, which took longer than I think either of us expected—the book was technically supposed to come out last year. But when that deadline came and went—and I explained that I needed more time, that I felt really close to solving the problem that delayed the book’s completion—she was so generous about giving me time. At every stage of the manuscript, she would ask really thoughtful, generative questions. And always with such kindness.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Nicole would often use the phrase “take it to the body,” which was a reminder and a challenge to stay in my body, even when I was uncomfortable, even when I was afraid. So much of writing poetry involves being radically present, and in the moments the poems were most challenging, I would make myself stay present by turning even more closely to my body, cataloguing its every sensation, even when—especially when—I wanted to turn away.

8. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

A lot of the poems in this book take place in childhood, which is not really where I’d spent time in my poems before this. Something about moving to California, the farthest I’ve ever been from my family and the places I was raised, allowed me to remember moments from childhood more vividly. Several of the poems contain a memory of my childhood years in Cairo, where I lived for two or three years as a young child, and the textures and architecture and sensations I remember from those days.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Girls That Never Die?

I did a lot of research that I didn’t even realize was research at the time. A lot of the questions that I was asking myself, that eventually showed up in the poems, I would throw into a group text with some friends—not because I knew I wanted to write poetry about them, but because I was just trying to work out the thought. And in those text threads I learned so much about our collective girlhoods and childhoods and shared wounds, the harmful things we all had been taught about our bodies and desires and ideas around reputation and honor.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I have a page full of notes from a talk given by Chris Abani at a Cave Canem event in, I think, 2014; I return to those notes all the time. Some jewels from it are: “A poem doesn’t exist to give information, it exists to give insight,” and “sentences are units of meaning, but a line is a unit of possibility.”