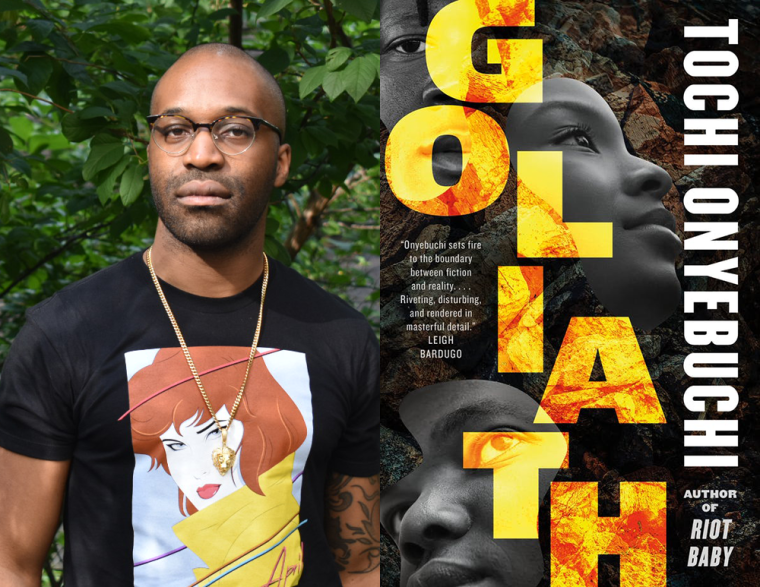

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Tochi Onyebuchi, whose latest novel, Goliath, is out today from Tordotcom. In the world of Goliath, humans are more segregated than ever. The most privileged have absconded to space colonies, while those who remain on earth suffer from the fallout of climate change and at the hands of “cyberized” police. In one scene on earth, a group of laborers look on as a friend is evicted by a “large metal sphere with arms like a spider.” Up in the colonies, a space-dweller named Jonathan convinces his lover, David, to move down to New Haven. “We’ll be like the pilgrims,” he says. With these contrasting worlds and a large cast of characters, Goliath offers a new staging of urgent issues of race and class. “Onyebuchi sets fire to the boundary between fiction and reality, and brings a crumbling city and an all too plausible future to vibrant life,” writes Leigh Bardugo. “Riveting, disturbing, and rendered in masterful detail.” Tochi Onyebuchi is also the author of the Beasts Made of Night series and War Girls series. His novella, Riot Baby, was a finalist for a Hugo, a Nebula, a Locus, an Ignyte, and an NAACP Image Award, and won the New England Book Award for Fiction and an American Library Association Alex Award. Among his degrees, he holds a BA from Yale and an MFA in screenwriting from the Tisch School for the Arts.

Tochi Onyebuchi, author of Goliath. (Credit: Christina Orlando)

1. How long did it take you to write Goliath?

The short story that served as its seed was written in the summer of 2013. No one wanted to buy it, so I let it sit for some time while working on other things. But I realized that the world and the characters had more to say and do than could be captured in a single short, so around the end of 2014 I returned to it and began writing some of the scenes that would become the “SUMMER” section of the book. I worked on it periodically since then.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I knew the scope I wanted it to have. Inspired by books like Neel Mukherjee’s The Lives of Others and A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James, I knew I wanted it to be a big book, physically and emotionally, but I didn’t know what that meant. I didn’t have the translation software to know what “big” would turn these characters and this setting and this narrative into. So much of the writing process was figuring that out.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Anywhere, all the time. Or, rather, whenever I’m not answering e-mails, which is an increasingly small amount of time. I used to write whenever—between classes, after finishing homework, during train commutes, and so on—back when the administrative work of “being a writer” didn’t overly intrude on the act of writing. But now I’m much more subject to the vagaries of “time-sensitive” e-mails, which means the “write when I can” has taken different shape. All of which is to say that there’s no rhythm or routine to my writing. I do it because I love it, which means I don’t need to be self-cajoled or self-bullied into doing it. I can’t avoid writing, not just because it pays my bills, but because it’s the thing I love to do more than anything in the world. It’s compulsion. It’d be easier for me to stop talking than to stop writing.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m doing some work-related reading that I can’t quite talk about, but next in my queue is Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. I’ve wanted to get to it ever since I first picked it up in 2016, but events conspired against me. I recently finished Mason & Dixon by Thomas Pynchon and found myself surprised by the humanity thrumming underneath the literary pyrotechnics and the kinda math-metal post-modernism of the text. Definitely more accessible than Gravity’s Rainbow.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

John Crowley. Which is maybe weird because he’s very much a revered figure for certain few generations of science fiction and fantasy writers. To be honest I think a lot of my picks might fall prey to that dynamic of being acclaimed in SFF, but poorly known outside of it. Crowley completely demolishes what may be a lingering prejudice against SFF: that the genre prioritizes plot over prose, that you can’t find some of the most beautiful sentences in the English language there.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Ah, the MFA Question. I loved my MFA program but for reasons that were specific to the program and that make me realize my MFA experience was, in many ways, a unicorn experience and not at all what appears to be the norm. My background is prose; I’d been writing it since I was maybe eight or nine or ten. By the time I was MFA age, I knew how to write a book—a publishable book, in fact—even if I hadn’t sold one yet. But I wanted to know how to write for film. I wanted to know how to write for TV. And I didn’t want to spend a decade and a half figuring it out, so an MFA in dramatic writing was an accelerant for me. It helped, I think, that I received instruction in a thing I didn’t already know how to do—I’d written a few features and some TV stuff before, but I was like a kid kinda messing around on the piano, not able to read sheet music—as opposed to something I was pretty sure I could do at a more-than-competent level. Another component was that my class was extraordinary. I had titanically brilliant writers for classmates, writers who’ve gone on to write for shows like Vida and The Underground Railroad. One classmate, in fact, wrote the script for Halle Berry’s directorial debut, Bruised. What served as foundation for our experience was the abundant love we had for each other. It was nothing but support in those workshops. We cheered each other in class, praised each other, celebrated each other, even as we pushed each other to improve. I’ve since discovered that a lot of MFA programs are not like that, and that even our year in that program was unique. But I wouldn’t trade that experience for the world. There’s a lot of writing stuff you can learn for free. I think the utility of a program can come from doing one in a field you’re unfamiliar with, where it can feel like you’re actually learning something new as opposed to being told what to do differently in a field you may already know. It’s easier to get pride out of the way for me that way.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

The ability to meet the story where it lives. Folks in those positions sometimes submit to the temptation to turn a client’s story into what they think it should be. But I think part of having real vision and talent in those positions is seeing in the story the best possible version of itself and having your tuning fork ring at the same frequency as the writer’s. I don’t think it’s the writer’s job to worry about marketability or about audience or about all the externalities that can determine or thwart a book’s success. That’s the ambit of publicity and marketing departments. The goal of the editor-agent dyad, I think, is to make the author’s book its most actualized self.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Goliath, what would you say?

I don’t know that I’d say anything. Novikov self-consistency principle notwithstanding, I’m still too frightened of potentially altering that boy’s course. So I’d just watch and smile.

9. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

Working on a book at all. Returning to the distinction between writing and being a writer, there’s a period after a book is written where processes attendant to publication begin to take over. Promo work begins, maybe adaptation talk ramps up, an ecosystem grows around the thing. As lovely as all that is and as blessed as I feel being able to live in those spaces, it’s not writing. The thing I’ll miss most about working on this book is working on a book, period. I take consolation in the fact, however, that there is more writing on the horizon.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Fail brilliantly.” I think I got that from Elizabeth Bear, but I may be misattributing it. But that’s gotta be it. Felt like I was being given permission to do the dangerous thing, the weird or unconventional thing, the thing I wasn’t quite sure I could pull off. Writing at the edges of my abilities thrills and terrifies me, and it’s in those moments that I feel most connected to whatever higher state or power this writing thing puts me in communion with. The advice isn’t just to do the dangerous thing, it’s to put all of your ability, your wisdom, your knowledge of the craft, your experience, all of that into the effort. Stretch yourself as far as possible. Who cares that you didn’t get the moon if you come back with a fistful of stars?