Seattle to Tulsa is a three-day journey by road. From the saturated green coast of fiddlehead ferns and roadside waterfalls to long, arid rings of inland prairie, mountains, and rivers of all description, all must be crossed. As Joy Harjo and I talk from our respective homes, her warmth makes the space diminish; I imagine the road between us beginning in Seattle, where I am, and crossing the Cascade mountains, to the towns of Cle Elum, Deer Lodge, Crow Agency, Cheyenne, Wichita, and Tonkawa. Cross the Arkansas River and there is Tulsa. The road is overlaid in concrete and numbered, but the paths have always been here.

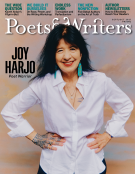

Joy Harjo (Credit: Julien Lienard)

Harjo is a traveler and a community leader whose experiences drive her storytelling. “My creative life, I have come to understand, finds energetics in traveling, either physically or through knowledge gathering,” she says, and these voyages inform the passages of poetry and prose in her new memoir, Poet Warrior, published in September by W. W. Norton. The book is told in six parts, and each movement opens for readers a different doorway to understanding the way lives and places intertwine.

Born in Tulsa, Harjo is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. She is the author of nine books of poetry, including An American Sunrise (2019), Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings (2015), The Woman Who Fell From the Sky (1994), and In Mad Love and War (1990), all published by W. W. Norton. Harjo’s first memoir, Crazy Brave (Norton, 2012), won the 2013 PEN Center USA prize for creative nonfiction. She has also published a children’s book, The Good Luck Cat (Harcourt Brace, 2000), and a book for young adults, For a Girl Becoming (University of Arizona Press, 2009). More recently she served as executive editor of When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations, published in August 2020.

Harjo is also a noted saxophonist and vocalist who performed for many years with her band Poetic Justice and currently plays saxophone and flutes with Arrow Dynamics. She has produced seven award-winning music albums, including Winding Through the Milky Way and I Pray for My Enemies. She has taught creative writing at the University of New Mexico, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), and elsewhere, and currently holds a Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Harjo is a founding board member of the Vancouver, Washington–based Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, a nonprofit whose mission is to advance equity and cultural knowledge, focusing on the power of arts and collaboration to strengthen Native communities and promote positive social change.

In 2019, Harjo was named U.S. poet laureate, the first Native American poet to hold the distinction, and is currently serving her third term. Last year she launched her signature laureate project, “Living Nations, Living Words,” an online map featuring work and recordings from forty-seven contemporary Native poets. In May, W. W. Norton published a companion anthology, Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry.

“We need rituals of becoming in which we are given instructions that define our relationship with becoming, with our relatives, those sharing the world around us,” Harjo writes in Poet Warrior. The new memoir is a profound story of the interconnectedness of becoming, illuminating the way that guidance comes to the learner in each season of life. One of the memoir’s most generous and tender passages proposes the following: “If grandchildren are evidence of our fulfilled dreams, then our grandparents are the dreamers and storytellers from whose imagination we arrive here.” In the memoir Harjo stands inside this generational reckoning of time and helps us to see it as a cycle. There is a powerful pulse in all the events that she describes, from traveling with an Indigenous dancing group, to young motherhood, to walking the original homelands of her nation. “What did you learn here?” is the gentle imperative that informs the power of her words, her leadership, and her guidance.

I am reading Poet Warrior with great curiosity, admiration, and pleasure. One feeling that I take from the beginning of the text is the primacy and clarity of breathing. This stood out to me because it made me realize that reading your work was affecting my attention not just to the text, but also to myself, my breathing, and my own surroundings. In Shawnee language the way we greet and ask after one another actually uses the verb to breathe, which is written as wesilaasamamo. It means that when we meet each other we are asking “How are you breathing?” I mention this because it made me curious about the role of breathing in your work and in the way Indigenous words and ideas can come up in literature.

When we take in our first breath, it is a promise to take on this human story, a story that has dimension in time and place. Breath is our entrance into story making—it is a promise. It is a constant ritual that we all share, and it is essential in poetry. Our phrasing and line making is based on breaths. To compose according to phrasing by breath or other means of rhythm counters a traditional method of composing by poetic form and measure.

However, if you look to the roots of poetry throughout Indigenous cultures in the world, poetry making is not without music, and music is not without dance. When I began writing and thinking in poetry, rhythm was primary, alongside image making. My first poems were conceived and written between all the tasks and requirements of being a full-time single parent and student and a part-time job holder. I wrote in the in-between, or during the very late hours, after the children were asleep. My poems were generally of short lines, like short, running breaths, and single-image-driven. I was also learning poetry as I wrote poetry. With self-confidence and continued study my breaths grew longer. With the collection She Had Some Horses [1983], especially the title poem, I became aware of chant language, of the language for long, sequential songs.

My job at the University of New Mexico’s Native American Studies involved arts research. I was learning that whatever was created in our tribal societies wasn’t for greed or influence but rather to be useful. And why not decorate and embellish that which is useful, like pottery, architecture, stories, or even songs and poetry? We have songs to turn a storm. Why not poetry? I followed language by rhythm and image to where it was going. I didn’t usually know where it was going. With the poem “She Had Some Horses,” a cadence overtook me. And wherever I was at the time I was writing that poem, which was either Santa Fe or Albuquerque, New Mexico, I needed healing, which meant my family was in need of healing. That cadence was maintained through rhythm, phrasing, and a relentless appearance of images that invoked what was needed for balance, hence: “She had some horses she loved; she had some horses she hated. These were the same horses.”

I didn’t know that until years after writing the poem. And, of course, in that poem is woven past, present, and future, and the gift with horses one of my great-grandfathers had, along with those who followed who had this gift with horses.

I have always been influenced by song language, as I came to poetry through my mother’s songwriting. When I started performing my poetry with my first band, Joy Harjo and Poetic Justice, and began performing with saxophone at that time, I became acutely aware of phrasing by breath, both with the voice and with the sax. Blowing horn and singing require similar technical feats, and breath holds out about the same length in speaking as with horn playing.

Orality is at the basis of poetry, as it is with story making. In each of my books of poetry since She Had Some Horses, I have attempted to make each one an oral event. The hardcover edition of The Woman Who Fell From the Sky [1994] included a cassette tape of reading and music, and musings and anecdotes following or threaded behind each poem. In A Map to the Next World [2000], the musings turned into fuller stories. A midsection included a poem that was a kind of call-and-response series, and a single poem that was a miniature of what the whole book attempted in a kind of mini oral performance. With Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings [2015], musings turned into stories, then riffs, like jazz riffs. And finally with An American Sunrise [2019], a map and excerpts of history threaded through the poems in a kind of oratorial storytelling and singing event.

The nature of quarantining has made us individually, and perhaps even collectively, more aware of the ritual of breath making. Our communities turned more directly to poetry and what poetry offers and has always offered. Poetry stops us even as it engages us with breath-rhythms that allow the kind of insight that comes with an intake of inspiration and an outtake of that which no longer serves us.

As I was reading Poet Warrior, I often noticed the way that my senses were pulled into the text. It made me feel I was breathing with it as a living conversation, and it created a magical suspension of linear time. It made me wonder about your process and the way you invite life into your work. Could you speak to the way you notice and gather ideas in your writing and in your memoir?

My memoir Poet Warrior is a kind of storytelling event that includes several modes of moving narratively and lyrically through a life or moments in time. I have never been very chronological or linear in my thought process. And in my way of working I listen and follow, and the form gathers, and I go from there. I revise continually as I write. I work ahead, far ahead if I am inspired. Then I return and untangle the mess and find a pattern and keep going, then circle back when I return, sort of like weaving, or sketching then filling out the image, or in the case of story writing, the narrative. Still, I am aware of rhythm. There is rhythm and timing, and the best storytellers have rhythm. And rhythmically I prefer to swing!

Poet Warrior came relatively quickly compared with Crazy Brave—I think because we were in quarantine, and I was approaching the pinnacle of an accumulation of years and wanted to pass on the lessons. And yet, because I was listening to what I didn’t know as I told the story, or series of stories, the book began forming. What emerged and surprised me as it surfaced was a long poem that winds through the book, a book in which Girl Warrior comes of age and in the coming of age discovers poetry. She eventually is given the name “Poet Warrior” as she passes from one age of becoming to another. This voice became a kind of through-line. And lines are inherently, I believe, breath-inspired. The book is a collection of stories, stacked not necessarily one on the other, but by merging by revelation rather than chronology.

I’d love to know how your time as poet laureate is going. Your projects are bringing such a sense of access and excitement to world literature. I just taught a class on “Living Nations, Living Voices” for both adult learners and Indigenous high school students. One thing that we talked about was your call to action: “Place is central to identity, to the imagery and shape of poems, no matter what country, culture, or geographical place. Now I urge you to make your own maps.” We ended class with everyone creating their own “maps,” and it was amazing the way your expansive framing made space for new thinking: Some folks were peeling pieces off old globes and replacing them with slips of poetry, others were tweeting out stanzas each hour, and one person was inking lines up her arms. It was amazing. What do you see as the possibilities of new maps of poetry and how they could change the way we engage with language and with one another?

I like that you call the poet laureate mapping project a “call to action.” I hadn’t thought of it as exactly that; however, every aspect of that project was about changing the narrative, even the vision of what it means to live in a country, the manner of citizenship, and to shift how the public imagines Native peoples, poetry, and place. Place is always present in a poem, story, or other creation, even if it’s a border, or placelessness.

A poem is a kind of map and/or mapping. There’s the literal aspect, as in oral cultures in which song-poems might embody star maps or escape maps. A map shows you a location, shows you where you are and possible destinations. Lines are roads. Images are destinations. Water and earth are concrete. Fire and air are insight and idea. Then we wind up someplace familiar, but we’d never heard it this way before.

In your work creating new anthologies of literature, including Living Nations, Living Words and When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, I’m interested in the way you organized the books geographically. Could you talk about the most remarkable thing you noticed in this pattern? Were there elements of sound, image, or language that you could stitch to place? I understand that you taught a class on how to organize an anthology, and I wonder if that unearthed any new ideas about organization and ordering?

I had not planned to publish two Norton anthologies of Native poetry within a year. Each evolved very differently. Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry is a companion anthology to my signature poet laureate project, which features a sampling of work by forty-seven Native Nations poets through an interactive ArcGIS Story Map and a newly developed Library of Congress audio collection. The anthology includes the poems along with images of the contributing poets. It is organized by direction, though each poet in the anthology isn’t always placed in their literal direction of place, rather in symbolic direction, such as East as a sunrise, or beginning point, and West as a place of ending, and so on.

When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry was released in October 2020. I began this project when I was the Chair of Excellence at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Because I had excellent support from the department of English, and the best assistant and students, I decided to finally take on assembling a Norton anthology of Native poetry. The way I started was to get permission to teach two classes, one in the fall and one in the spring. Each would be a class on Native poetry, even as the classes were on how to edit and assemble a Norton anthology. Each semester was very different. The students in the first class were involved in discussions of organization, concepts, setting up tasks of compilation and editing. The second class, we were further along in the process and the students assisted with proofing, creating bios, and other aspects of editing. We had many guests who visited the classes on Skype—this was pre-Zoom days—including permissions editor Fred Courtright, Jill Bialosky, senior vice president at Norton, who has edited and overseen many Norton anthologies, and others. What was central to the process was the team of Native poets who assisted as coeditors. We agreed to arrange the anthology by areas of the country, by land location rather than chronology or another order. Each team met periodically on Skype with my students as we edited the anthology. This was my favorite part of the process because we were reading extensively and discussing poetry, and my students were part of it.

Because of the organization by area of the country, we were able to see in the poetry how and when colonization hit and how it affected even the creation of poetry. We could see how colonization moved relentlessly from all directions as it devoured lifeways and languages. Those from the East and the South were particularly hard hit early on. Eventually everyone suffered. Overall we had a nearly impossible task. How do you fit a collection of poetry that is to cover from time immemorial to present day, with more than 574 federally recognized tribal nations, the state recognized tribal nations that are genuinely tribal nations, and Hawaiian or Pacific-related groups into three hundred fifty pages? We were given more pages as the project progressed. That we are still functioning, creating, and even thriving in our diverse cultural systems—our poetry is a testament to the spirit of our peoples and to the power of the spirit of the land for sustaining us in body and mind and spirit.

Part five of your memoir is titled “Teachers.” We share an alma mater, the Institute of American Indian Arts. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on your education and how it fed or starved your creative growth. I hold that I could not have become a writer without the formative experience of coming to literature in an Indigenous setting with other Indigenous writers. I remember, when I was a student at IAIA in the late 1990s, that you visited once and made time to meet with each and every writing student. It is an act of generosity I have never forgotten. When I was young one of my elders showed me how to grow corn by holding my hand flat to the earth—you slide the seeds down your wrist and bury them finger deep. When the shoot comes up to your elbow, you put your palm to the ground again and put a bean at the tip of each finger. I think the best writing leadership and mentoring is like this—practical, invested, and nourishing. Thank you for your years of dedication to Native writers. Is there anything you would like to say about your teaching philosophy and place as a mentor and leader for writers?

Every teacher has teachers. When I was a student at IAIA it hadn’t transitioned to an arts college. IAIA was still a Bureau of Indian Affairs School with a newly constructed arts education. We were mostly a high school with a two-year postgraduate program. We had the best arts instructors. Most were Native and some non-Native. Having Native teachers was a first for me, even though I came from Tulsa, a city with a relatively large population of Native residents. Teachers at IAIA were very dedicated and knew that we were all part of an innovative concept in Indian education. It was an exciting time of fresh ideas in the arts. I didn’t take any writing classes there. I was going to be a painter, but by second semester I was studying drama and dance and became one of two high school students who were included in the postgraduate drama and dance troupe. Our teachers knew their craft; they were professional working artists, and they cared about us. I learned about teaching from them.

When I was an undergraduate at UNM, I was one of the students chosen by my poetry professor Gene Frumkin to assist in the Poetry in the Schools program. I was inward and shy, but I learned. And I learned there’s nothing like the delight of a student who creates a poem, and there it is, on paper. It’s a kind of magic for student and teacher, to share in study and creation. That teacher and my other poetry professor, David Johnson, organized student readings and even took us to writing conferences in and near the state. I met Yusef Komunyakaa on one of those trips to Colorado. He was just out of the military. He won first place in a contest. I won second. That kind of belief and attention meant everything. I later went on to return to IAIA to teach, then taught at the University of Colorado in Boulder, the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, the University of Arizona in Tucson, and UCLA.

By the time I started teaching at UCLA I was in a crisis of faith about my teaching. I was aware that my methods of focusing on orality and relationship ran counter to prevailing pedagogy. There was nationwide resistance in academic institutions to teaching multicultural and diverse forms of American literature and thought. It was often quite a struggle to show up. One day a student brought her friend visiting from out of town to my office hours to meet me. Her friend loved my poetry. As they stood in the doorway of my office waiting for their turn, I overheard my student tell her friend, “I wish she taught the way she wrote.” That stung, but it was exactly what I needed to hear. I had begun getting caught up in teaching in a manner that didn’t fit with my style, knowledge, or abilities. I had grown stiff and inflexible, as if my enemy was at my shoulder deriding me at every word. I have learned that teaching is an art. It is one I deeply respect. I love hearing from my students, who now span years, even generations. They have given me grand students.

There is a beautiful line in your memoir: “A family is essentially a field of stories, each intricately connected.” This line made me think of something that you often mention in interviews, a “poetry ancestry tree.” I wonder if you could talk more about these images, of the tree and the field of stories.

This is one of those profound teachings that I will always be in the middle of comprehending and learning. The teachings never end, and revelations follow one after another. That is the nature of study and of learning. Being a teenage mother was difficult, but it gave me the perspective that comes from being a grandmother in my thirties and now a great-grandmother for five years. Because of this I have come to see generations of family as a continuum, as an ongoing story field. The same is true of poetry. Each generation of poets makes a ring of poetry. We influence one another, whether we are aware of it or not, and not just in our particular style or cultural circle or school. Each generation is one ring upon another, and there is movement in nearly every direction. By calling an influence an ancestor rather than an influence, a relationship is made, a kinship. Some of these connections resonate and flower, while others challenge and force us to stand up. The best we can do is listen, pay attention, and give back as profoundly as it was given to us.

Laura Da’ is a poet and teacher. A lifetime resident of the Pacific Northwest, Da’ studied creative writing at the University of Washington and the Institute of American Indian Arts. Da’ is Eastern Shawnee. She is the author of Tributaries, winner of the American Book Award, and Instruments of the True Measure, winner of the Washington State Book Award, and lives near Renton, Washington, with her husband and son.