June Jordan was born in Harlem in 1936 and was the author of ten books of poetry, seven collections of essays, two plays, a libretto, a novel, a memoir, five children’s books, and June Jordan’s Poetry for the People: A Revolutionary Blueprint. As a professor at the University of California in Berkeley, Jordan established Poetry for the People, a program to train student teachers to teach the power of poetry from a multicultural worldview. She was a regular columnist for the Progressive, and her articles appeared in the Village Voice, the New York Times, Ms., Essence, and the Nation. After her death from breast cancer in 2002, a school in the San Francisco School District was renamed in her honor.

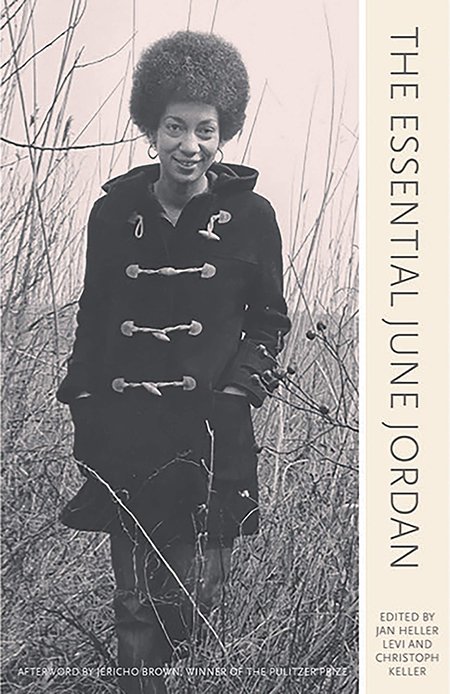

The Essential June Jordan, edited by Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller, will be published by Coppy Canyon Press on May 4, 2021.

On May 4, Copper Canyon Press will publish The Essential June Jordan, edited by Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller. Below is the book’s afterword by Jericho Brown.

![]()

June Jordan’s “Roman Poem Number Thirteen”—near the beginning of this collection—seems to me the best example of Jordan’s poetic legacy. It mixes the doom and devastation made mundane through media with the hard decision to love anyway, because “There / is no choice in these. / Your voice / breaks very close to me my love.” In other words, it moves past evil to see people, community, the possibility of romance. And this is the trajectory we see in every line she writes for her entire career, as here:

it is this time

that mattersit is this history

I care aboutthe one we make together

awkward

inconsistent

as a lame cat on the loose

or quick as kids freed by the bell

Because Jordan is a love poet in the midst of the Black Arts Movement and the Civil Rights Movement—and in the resulting movements these would spur on—she expresses her talent such that what is erotically felt manifests as a singular ferocity that even she seems surprised by: “WHAT IS THE MATTER WITH ME? // I must become a menace to my enemies.” We should be clear, though, that Jordan’s sense of resistance is at the root of what we now call intersectionality. She understands—this is important because she publicly fought leading artists and intellectuals who did not understand—that liberation for Black people means liberation of the spirit, liberation for the natural world, and liberation from imperialism. Her very famous “Poem About My Rights” is at its outset a poem about wanting to take a walk, a poem about the difficulty for a Black woman to do what anyone does when taking a walk:

suppose it was not here in the city but down on the beach/

or far into the woods and I wanted to go

there by myself thinking about God/or thinking

about children or thinking about the world/all of it

disclosed by the stars and the silence:

Jordan sees that it is the violation of the simplest acts that leads to violations in housing, voting, education, and the body. And her response embodies this vision. She writes, “I can tell you that from now on my resistance / my simple and daily and nightly self-determination / may very well cost you your life.”

Yes, small, mundane observations in Jordan’s poems often lead to the truth of their dire implications. And sometimes her poetic practice moves in the opposite direction as well, leading the reader to understand just how mundane evil has become. In “Fourth poem from Nicaragua Libre: report from the frontier,” she writes: “when the bombs hit / leaving a patch of her hair on a piece of her scalp / like bird’s nest / in the dark yard still lit by flowers.” The use of juxtaposition, simile, and sound is extraordinary here, but the content itself…for June Jordan, all the beauty of poetry comes at a cost.

Sometimes, the beauty isn’t worth the price of what some see as normal, and Jordan’s fury rises past well-wrought image to open confrontation made through rhetorical intensity:

Tell me something

what you think would happen if

everytime they kill a black boy

then we kill a cop

everytime they kill a black man

then we kill a copyou think the accident rate would lower

subsequently?

All this calling out, though, is so that the mundane can

indeed be just that and enjoyed as such:I might begin another list of things to do

that starts with toilet paper and

I notice that I never jot down fresh

strawberry shortcake: never

even though fresh strawberry shortcake shoots down

raisins and almonds 6 to nothing

effortlessly

effortlessly

Jordan’s work carries a commitment to Black vernacular, helping pave the way for much of the contemporary work by Black writers that we read in major outlets today. She understood the phrase “standard English” to be a racist one: “There are three qualities of Black English—the presence of life, voice, and clarity—that intensify to a distinctive Black value system that we became excited about and self-consciously tried to maintain.” Hence, we are fortunate to have poems that Jordan begins as only a Black person could, such as “My born on 99th Street uncle” and “Sugar come / and sugar go / Sugar dumb / but sugar know.”

I believe our love for June Jordan as a poet of the people is encouraged by the ways her work reaches to protect us and by the fact that “us” knows no limits in sex, sexuality, gender, race, or location. But the root of our love is that Jordan understood herself as us, “I was born a Black woman / and now / I am become a Palestinian.... It is time to make our way home.” Her protest on behalf of the fact of bisexuality is built out of shared eros rather than antagonistic claim: “Can you give me the statistical dimensions / of your mouth on my mouth / your breasts resting on my own?” Jordan is always busy trying to be a person in love, trying to live her right to be loved:

I wanted them to know it’s not cheap

or disgusting to love a Black

revolutionary and

as a matter of fact

I wanted them to know you’d

better love a Black revolutionary before she

gets the ideathat you don’t.

The legacy of June Jordan is a gift to us in that it allows another opportunity to think not only about what poems are, but also about what poems can do. Can a poem love you?

Jericho Brown is author of The Tradition (Copper Canyon Press, 2019), which won the Pulitzer Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, and the National Endowment for the Arts, and he is a winner of a Whiting Award. Brown’s first book, Please (New Issues, 2008), won the American Book Award. His second book, The New Testament (Copper Canyon Press, 2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. His poems have appeared in the Bennington Review, Buzzfeed, Fence, jubilat, the New Republic, the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Paris Review, TIME magazine, and several volumes of the Best American Poetry. He is a professor and the director of the creative writing program at Emory University.