Nancy Hathaway has written books on astronomy (The Friendly Guide to the Universe), photography (Native American Portraits), mythology, astrology, and more. Her shorter pieces have been published in periodicals that range from Alimentum and PaperTape to American Recorder and Self. She lives in New York City.

In 2009 I was invited to lead a writing workshop at St. Margaret’s House, an independent-living facility for the elderly and disabled that operates in lower Manhattan under the auspices of Trinity Church. The prospect excited me, except for one thing: The members of the workshop, which is funded in part by Poets & Writers under its Readings & Workshops program, had been meeting for years with another writer. Their community, I imagined, was fully established, and I wasn’t certain I would fit in.

I also didn’t know how to begin, though I’d taught composition many times. My friend Sally, a veteran workshop leader, suggested that I bring something in for the first day. Everyone likes a handout, she said. So I printed out a page of quotations about writing. There were inspiring passages from Kafka and Annie Dillard, along with rueful pronouncements from William Styron (“Let's face it, writing is hell”), Joy Williams (“Nothing the writer can do is ever enough”), and Flaubert (“Writing is a dog’s life, but the only one worth living”). These downbeat quotations from distinguished writers reassured and consoled me. Writing is hard—and I’m not the only one who feels that way. I was sure the writers of St. Margaret’s House would relate.

But they did not relate. As I ran through my quotations, they seemed mystified and faintly hostile. Why, they wondered, would Willa Cather believe, “Most of the basic material a writer works with is acquired before the age of fifteen”? That couldn’t be true. (Flannery O’Connor upped the age to eighteen.)

And, sexism aside, why would Donald Barthelme say, “A writer is a man who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do”?

And what did Red Smith mean about opening a vein?

I tried to explain. Eventually a septuagenarian in a floral blouse asked if we could change the subject and talk about Hemingway.

Absolutely.

She said that a series of electro-shock treatments had wiped out his memory. He couldn’t write, and that’s why he committed suicide, and what did I think about that?

I said I thought it was a tragedy.

She couldn’t stop thinking about it, she said, whereupon a luminous, white-haired woman at the other end of the table leaned forward, eyes blazing. “When did that happen?” she demanded. “1961? 1962? Get over it!”

By the end of the session, I was worried. Timed writing exercises on specific topics had not gone well, and free-writing was a disaster. Leading this workshop was going to be rougher than I thought.

That was almost five years ago. Since then, despite diminished hearing, vision problems, mobility limitations, and other age related torments, most of the people I met that night (and a few new ones) show up weekly, pages in hand. Their writing has improved, as have their critical skills. Honest and encouraging in approximately equal measure, they really are a community, and I am honored to be part of it.

I date the turnaround to the third session, when I brought in two poems: “The Game” by Marie Howe and “Scrabble in Heaven” by Jane Shore. After we talked about them, I asked everyone to write about a game, and I set my iPod ticking. The results astonished me. A retiree who had been paralyzed by random prompts wrote nonstop about Monopoly. A former professor conjured up a long-ago badminton game. A second-wave feminist (and well-published journalist) tied a cogent political analysis to the plunder and betrayal involved in the board game Risk. There were pieces about checkers, dominoes, and Twister, and even a rumination on Freecell, the online solitaire game. Playing Freecell, wrote the Hemingway fan, “My breath becomes even, my blood oxygenated.”

Since then, we have read a lot of poems, and the workshop has been transformed. Poems are better than prompts, even when they are used as prompts. Standard prompts may stir up memories but they offer nothing by way of literary models. Poems do that and more.

First, they show how other writers excavate sensitive material and thus they are liberating. Have mixed feelings about your niece? Read Louise Glück. Your father? Start with Roethke and go from there. Anxious about, say, cancer? Read Elise Partridge, Rosanna Warren, and, while you’re at it, Whitman. Poetry peeks into every heart and under every stone. It reveals all—and it’s short.

I like to bring in paired poems – W. H. Auden and William Carlos Williams on Breughel, for instance – but mostly I use individual poems. Stephen Dunn’s “Death of a Colleague” caused a commotion, raised voices and all. Katrina Vandenburg’s “Handwriting Analysis” inspired an essay that I am positive will become one woman’s first outside publication. Christopher Smart’s “Jubilate Agno,” written circa 1760, occasioned an ode to the pharmacy chain Duane Reade.

A writing workshop is not meant to be a literature class. But how can it not be? Even for writers of prose, reading poetry illuminates subject matter, disentangles emotions, highlights the importance of craft, and demonstrates precision in language.

But there is one thing it cannot do: persuade writers to rewrite—not merely to make isolated corrections but to rethink, rephrase, even reorganize. Rewriting is a complex business, and many members of the workshop resist it.

I don’t blame them. Rewriting can be tedious (and worse). Still, every spring, as the deadline for our annual literary review—a booklet—draws near, the workshop participants sit down with their stories, personal essays, and occasional poems and, I am happy to say, revise.

I attribute that miracle to the power of publication. Because poetry is stimulating, and self-expression is valuable and satisfying, but publication, however humble, reaches beyond the self, beyond the workshop, and into the world. Publication galvanizes.

Top: Nancy Hathaway. Photo Credit: George Sussman.

Bottom: Journal 49. Photo Credit: Nancy Hathaway.

Support for Readings & Workshops in New York City was provided, in part, by funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

We’ve all heard Thoreau’s declaration, “I went to the woods to live deliberately….” Considering that Walden resulted, maybe he should have written, “I went to the woods to write deliberately….” Thoreau probably wasn’t the first whose writing was fueled by a natural setting, and he certainly wasn’t the last.

We’ve all heard Thoreau’s declaration, “I went to the woods to live deliberately….” Considering that Walden resulted, maybe he should have written, “I went to the woods to write deliberately….” Thoreau probably wasn’t the first whose writing was fueled by a natural setting, and he certainly wasn’t the last. My time in Tahoe led me to teach workshop-based courses at the High Sierra Institute (HSI), a satellite campus of the Yosemite Community College District, at Baker Station, a 1930s field station owned by the U.S. Forest Service. While HSI isn’t in the backcountry, it’s in the middle of the Sierra Nevada far from serious civilization. The remote locale creates a setting devoid of distractions, including cell and internet services. Participants come to HSI and drop anchor, staying there (for free) during the duration of the course. Our lives become suspended as we enter three-day weekends of writing. HSI’s unplugged nature and the absence of personal responsibilities opens up mountains of time. We devote roughly ten hours a day to examining, discussing, producing, and sharing writing, all sprinkled throughout the day. The other time is spent taking siestas, sharing meals together, sitting next to the Stanislaus River or around the campfire, walking, reflecting. This kind of isolation and immersion, something few of us find in our regular lives, fuels our pursuits on the page.

My time in Tahoe led me to teach workshop-based courses at the High Sierra Institute (HSI), a satellite campus of the Yosemite Community College District, at Baker Station, a 1930s field station owned by the U.S. Forest Service. While HSI isn’t in the backcountry, it’s in the middle of the Sierra Nevada far from serious civilization. The remote locale creates a setting devoid of distractions, including cell and internet services. Participants come to HSI and drop anchor, staying there (for free) during the duration of the course. Our lives become suspended as we enter three-day weekends of writing. HSI’s unplugged nature and the absence of personal responsibilities opens up mountains of time. We devote roughly ten hours a day to examining, discussing, producing, and sharing writing, all sprinkled throughout the day. The other time is spent taking siestas, sharing meals together, sitting next to the Stanislaus River or around the campfire, walking, reflecting. This kind of isolation and immersion, something few of us find in our regular lives, fuels our pursuits on the page. Every summer I see impressive writing emerge like magic. As much as I’d like to take credit for the prose produced, the setting has as much to do with the experience’s successes as anything else. We breathe the alpine air, hear the river’s running water, look up at mountains studded with granite boulders among towering pines, sit in a nearby meadow, and something shifts inside. A calming happens. It’s as if all that beauty takes hold of us and inspires us to be true to our stories, to be true to ourselves. It’s not uncommon for writers to explore narratives about deeply personal events that they’ve wanted to write about for years but have been unable to. And once one writer shares such a piece, which always happens, the others come forward, as if an impediment is dislodged, and important stories flow forth. This process produces a lovely level of trust among the group members, one that tacitly illustrates that this space and time are about creating and respecting our stories. While most share their work, I do not require that everyone do so except at the end for a final reading. My point is that while not required, everyone usually shares willingly because of the trust that results from the relaxed and accepting atmosphere created by the environment.

Every summer I see impressive writing emerge like magic. As much as I’d like to take credit for the prose produced, the setting has as much to do with the experience’s successes as anything else. We breathe the alpine air, hear the river’s running water, look up at mountains studded with granite boulders among towering pines, sit in a nearby meadow, and something shifts inside. A calming happens. It’s as if all that beauty takes hold of us and inspires us to be true to our stories, to be true to ourselves. It’s not uncommon for writers to explore narratives about deeply personal events that they’ve wanted to write about for years but have been unable to. And once one writer shares such a piece, which always happens, the others come forward, as if an impediment is dislodged, and important stories flow forth. This process produces a lovely level of trust among the group members, one that tacitly illustrates that this space and time are about creating and respecting our stories. While most share their work, I do not require that everyone do so except at the end for a final reading. My point is that while not required, everyone usually shares willingly because of the trust that results from the relaxed and accepting atmosphere created by the environment.

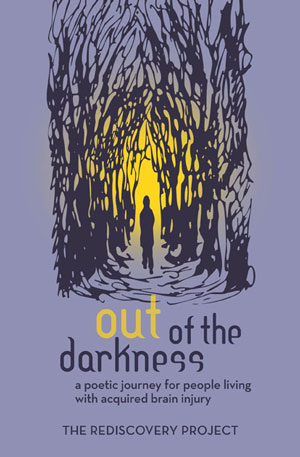

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be.

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be. The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter.

The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter. Somewhere in the Bronx there is a community garden called Hispanos Unidos. There, a cherry tree produces thirty pounds of cherries annually. Cucumber, cabbage, beans, figs, jalapeño peppers, peaches, and eggplants are grown and harvested. Tinkerbelle the cat guards the flock of chickens that live underneath the makeshift house. Inside the house on a wall is the worksheet for those who maintain the garden. The membership is ten dollars per month for men, five for women. The house serves as site of inquiry and celebration and as a location where Latinos maintain their cultural ties and language. It is a place where one can disregard the actual city residing outside the gates of the garden, where one can find respite in an array of fruits and vegetables. Where a rooster crows above the overhead subway train. It is gardens like this one that became the inspiration for Lincoln Center’s La Casita poetry and music festival.

Somewhere in the Bronx there is a community garden called Hispanos Unidos. There, a cherry tree produces thirty pounds of cherries annually. Cucumber, cabbage, beans, figs, jalapeño peppers, peaches, and eggplants are grown and harvested. Tinkerbelle the cat guards the flock of chickens that live underneath the makeshift house. Inside the house on a wall is the worksheet for those who maintain the garden. The membership is ten dollars per month for men, five for women. The house serves as site of inquiry and celebration and as a location where Latinos maintain their cultural ties and language. It is a place where one can disregard the actual city residing outside the gates of the garden, where one can find respite in an array of fruits and vegetables. Where a rooster crows above the overhead subway train. It is gardens like this one that became the inspiration for Lincoln Center’s La Casita poetry and music festival.

Second-place winners in poetry and fiction will receive a full tuition waiver for the two-week program of their choice; third-place winners will receive a 50 percent tuition discount. All qualifying entries will automatically be considered for

Second-place winners in poetry and fiction will receive a full tuition waiver for the two-week program of their choice; third-place winners will receive a 50 percent tuition discount. All qualifying entries will automatically be considered for