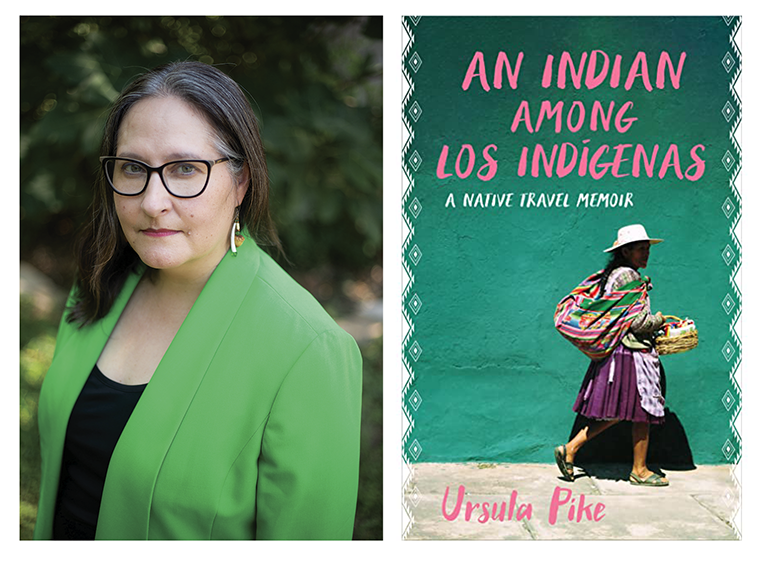

Ursula Pike, author of An Indian Among los Indígenas: A Native Travel Memoir, published in April by Heyday Books. (Credit: Stephanie Macias Gibson.)

I arrived in La Paz as four rum and Cokes joined forces with an altitude-induced headache. The other volunteers in the group had accepted the airline’s complimentary drinks, and I assumed this was what people did on international flights. Now I stood in the tiny airport that teetered on the rim of the bowl-shaped valley of the city, feeling exhausted and unprepared. Wood-paneled walls didn’t keep out the chilly air blowing across the high plateau. The T-shirt I had put on the night before in Miami provided no warmth. I forced myself to stand up straight despite wanting to lie down under something soft and warm. It was 7 a.m., and I was thirteen thousand feet above sea level.

I stepped into a quickly forming line leading to a Bolivian immigration official. His pale pockmarked face and broad unsmiling cheeks made me wonder whether he was part Indian. Native. Indigenous. Bolivia had four million Indigenous people. That was almost twice as many Natives as in the United States. In Bolivia, Indians were the majority. I bit my lip to keep from grinning.

The Bolivian official scanned passports without a greeting or a smile, quickly looking at each person’s face, then back at the passport. I stepped in front of the table where he sat and pulled my stiff passport out of the fanny pack my mother had given me before I left Oregon. Behind him was a shawl-sized painting of the red, yellow, and green Bolivian flag.

The other volunteers shuffled toward the immigration official. I had met them only forty-eight hours earlier, but I already knew exactly how many brown people were in the group. It was a tally I always made. A cute Latina from Texas, a midcareer Mexicano, a bleary-eyed Puerto Rican man, an athletic Filipina from California, and a broad-shouldered Filipino who was quiet except for the occasional self-deprecating joke. I didn’t like the term minority, but in this case we were. The remaining twenty volunteers looked like those combinations of Western and Eastern European identities that qualify as white in the United States. Did anyone wonder what I was? My dark brown hair and olive skin gave me a vaguely ethnic look. Teachers and curious grocery clerks usually guessed Hispanic or maybe Greek. My identity was a tailless donkey they had to pin the right kind of brown to.

The immigration official looked up at my face and then down at my passport. I was excited to be standing in front of a Bolivian for the first time, but the formality of the moment made me nervous. His thick eyebrows moved up and down as he scrutinized me. Then he stamped it, handed it back to me, and reached for the next one. That wasn’t what I had expected.

“Thank you for coming to my country. I can tell you are more serious than any of these gringos,” said No One. I looked around at the other officials. Didn’t my sincerity show through my olive skin? Maybe it was too early in the morning. Maybe they were rushed. I waited an extra moment to give him a chance for a second look or a nod of his head. Certainly, the Bolivians would eventually recognize that I was different from the others arriving from the United States that day. They would see that because I was an American Indian, we shared a connection. Coming to a country like Bolivia, a country full of Native people, had been the secret wish held in my heart as I filled in the spaces on the Peace Corps application. Couldn’t the Bolivians see that we shared a connection? Couldn’t they see that my commitment was more meaningful because I was Native? The person behind me sighed, and I reluctantly moved forward.

The training group’s luggage sat in a heap on the floor. My backpack, which had seemed so big in the REI outlet store back in Portland, now looked ridiculously small. The tiny straps and water-resistant pockets held two years’ worth of tightly packed clothes and supplies. As the other volunteers pulled their luggage from the pile, I tried to recall who everyone was. Even after ice-breakers and introductions, I could not remember anyone’s name.

Bursting leather suitcase—the athletic girl from California.

Floral-print handbag—Latina chick from Texas.

Worn North Face backpack—blond guy from Minnesota who had been smiling nonstop for two days.

The woman from Texas pulled another suitcase and more floral-print bags from the pile. Her name was Laura. The impracticality of her luggage choice made me love her. I had found my first friend. I hadn’t known what to bring, but had assumed everyone else had it all figured out. Laura must have brought everything she owned in case she needed it. She was an interior designer from El Paso, which sounded exotic to me, but she assured me it wasn’t. With a Marilyn Monroe figure and the longest eyelashes I had ever seen, she was glamorous and the opposite of what I expected a Peace Corps volunteer to look like.

“Don’t tell anyone, but I’m not fluent in Spanish,” she confessed over beers in Miami. Her mother taught her to speak English without an accent. We’d both been raised by mothers who taught their children to be proud of their heritage without appearing too “ethnic.”

“I won’t, if you don’t tell them I’m too fat,” I said. She laughed long enough to erase the embarrassment attached to the invitation letter informing me that I was three pounds above the acceptable weight for my height. For months, I worried there would be a scale at the airport with a trap door underneath ready to whoosh me back home if the wrong number appeared.

We followed the blond volunteer with the smooth southern drawl who was leading the way into the main part of the terminal. Round faces and short women wearing bulky skirts were everywhere. Long, dark braids hung down from black bowler hats that sat askew on their heads. They were Aymara women, Indigenous celebrities. Like the immigration official, none of them gave me a second look. I hoped that once I was apart from this gaggle of North Americans, I would be noticed.

In the parking lot on the high plateau where the airport stood, the sun felt a few miles away. I shaded my eyes with my hand and squinted to see a rumbling school bus waiting to take us to the Peace Corps offices. That’s when I saw Mt. Illimani. The mountain’s triple peaks loomed over the valley beneath us. It peeped over the rim of La Paz like the Abominable Snowmonster in the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer Christmas special. The wind pushed into the side of my face, whipping my hair from the barrette holding it down. Between the sunshine and the frozen wind, I was now fully awake. My heart beat faster from a combination of altitude and excitement. I was finally standing in Bolivia.

From An Indian Among los Indígenas: A Native Travel Memoir by Ursula Pike (Heyday, 2021).

Read Ursula Pike’s essay about writing An Indian Among los Indígenas: A Travel Memoir in the November/December 2021 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.