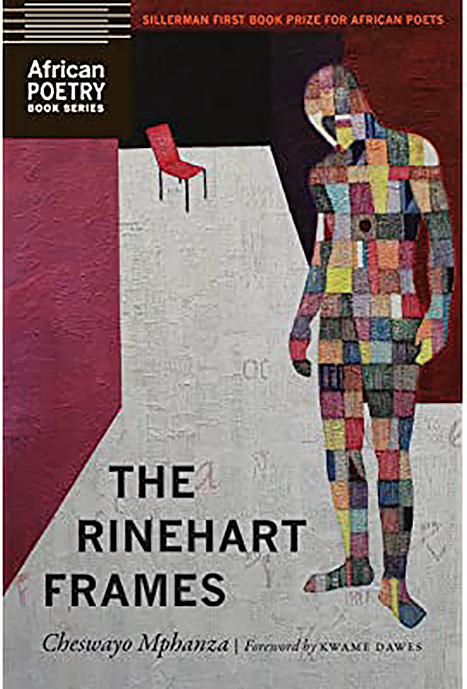

Cheswayo Mphanza

The Rinehart Frames

University of Nebraska Press

(Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets)

How do I reach a home aside from the imagination?

An image insists.

—from “Frame Eleven”

How it began: For a while I truly believed I was going to be a doctoral candidate in cinema studies and not have anything to do with poetry or any kind of literary writing for a while. So after graduating from my MFA program at Rutgers University–Newark in 2018, I took the summer to absorb and learn as much as I could about the craft and history of cinema. I spent a lot of my time going through second wave Iranian cinema (particularly the films of Abbas Kiarostami and Forough Farrokhzad), postcolonial and new wave African cinema (Ousmane Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty, Abderrahmane Sissako, Moussa Touré, Andrew Dosunmu, and Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, among a few), and Russian cinema with the works of Mikhail Kalatozov and Andrei Tarkovsky. Simultaneously, I noticed a narrative aesthetic akin to film language developing in my own writing of poetry. And I think that naturally just started informing my own ideas about poetry and how I was thinking about it as a craft and tradition I was placing myself into. What ultimately triggered a concrete idea of how the book was to be a conversation between art, history, and politics were two films: Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (1997) and Raoul Peck’s Lumumba (2000).

Inspiration: I went through a lot of the imagist/objectivist writings of Ezra Pound and Lorine Niedecker. I can barely remember a particular poem by the two if you asked me, but I think I was more so drawn to objectivism/imagism as a theory for getting as close to the poem as possible. It was easy for me to understand the description of a scene in cinema with how the imagist/objectivists framed spaces and people. In these moments that this description happens, what becomes erased or left in the margins? With that in mind, I was led back to the Oulipo, a collective Cathy Park Hong introduced me to. I was enamored by how the Oulipo writers are interested in restraints as a praxis for writing—living. I was beginning to understand how imposed limitations in language—and it being conveyed through writing—mirrored some of my own failures of synchronizing cinema and poetry and the complexity of displaying my Blackness on the page. Hence the book is framed around centos as points of demarcation. Hence I referenced the character of Rinehart in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. And the goal from there became even clearer: to construct a protagonist who was an amalgamation of others as the ultimate restraint because it is making sense of your existence as an act of curation, imitation, hesitation, and all the etceteras attached.

Influences: A. Van Jordan’s work in M-A-C-N-O-L-I-A (Norton, 2005) and The Cineaste (Norton, 2013) will always be the foundation for the first instance (to my knowledge) where I saw film and poetry synthesized to that level of literature. Nathaniel Mackey’s infinite poems “Song of the Andoumboulou” and “Mu,” which remind me of how the poem(s) can take up their own lives and be persistent in how they continue to resound on the page. I know I mentioned Tarkovsky, but I must invoke his name again. I was introduced to his film essays Sculpting in Time by a friend and filmmaker, Musa Syeed. I still haven’t being able to look back after reading that gorgeous work.

Writer’s block remedy: I can’t say I ever reach an impasse in my writing. For all intents and purposes, I love the labor of research and writing. I am obsessed with the process and revel in going through its many stages to reach the iteration that, after careful and tedious deliberations, I have settled on calling the finished product. There is always more work to be done and ideas visit me often, but I have to make do with this one lifetime I have and settle on what I can do to the best of my abilities.

Advice: It truly is a marathon. Especially given the fact that what we do exists in such an insular community of people who are also running their race to construct this thing that will be brought forth into the world and be collectively judged in whatever capacity. I say all that to say: Take your time with the craft aspect of it. Develop a language for your project that isn’t entirely composed of your affective responses to the world, but a combination of affect, intellect, and being in the world–ness.

Finding time to write: As I am working toward a novel project of sorts, so much of my writing now is taking notes of everything I am consuming pertaining to literature, music, cinema, and theory. The research takes up months and perhaps will go on for years. The writing will happen in a brief amount of time. So it is not that I necessarily try to find time to write, but I eventually lead myself to the writing when all the grunt work has been settled.

Putting the book together: A. Van Jordan published an essay with the Cortland Review titled “The Synchronicity of Scenes.” The essay is essentially a practice of understanding linear and nonlinear time. How does the world build around us, and how do we walk through it? It reminds me of Renee Gladman’s Ravicka series of novels in which the protagonist(s) exists in what I am calling a fluid relationship to the world. Every single action or motion influences the stability of the world and how it receives you. I wanted the order to feel as if the narrative of Rinehart in the collection was a performance of disturbance. So the prologue is an announcement of the self and what follows are a series of digressions somewhat related to the self. Everything is splayed, and the act of reading becomes an attempt to reach a fulfillment of the self that is ever so evasive and elusive.

What’s next: I am working on a novel with the working title “The Afronauts.” It is based on the life of Zambian revolutionary Edward Makuka Nkoloso, who in the early 1960s proclaimed Zambia would win the space race before the United States and the Soviet Union. He created an unorthodox space program to say the least. What I want to essentially accomplish in the novel is a riff on his life. His story is fascinating for thinking about Afrofuturism, Black Absurdism, and metafiction. As guiding lights, I am thinking of the writers Simeon Marsalis, Jorge Luis Borges, Clarice Lispector, John Keene, Percival Everett, Miguel de Cervantes, Renee Gladman, Dany Laferrière, Gail Scott, and Roberto Bolaño, among others.

Age: 28.

Residence: Chicago.

Job: I teach workshops here and there, but I am transitioning toward a full-time freelance job copywriting and editing.

Time spent writing the book: About a year, and another year for editing and publishing.

Time spent finding a home for it: I had an idea of where I wanted my work to have a home so I developed a list of five spaces to submit to. I was fortunate enough to have been picked up by one of the publishers within five months after the submission.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I have been so excited by the publication of Ananda Lima’s Mother/land (Black Lawrence Press), Tracy Fuad’s about:blank (University of Pittsburgh Press), and Antonio de Jesús López’s Gentefication (Four Way Books). I think these are all incredible poets carefully weighing what it means to create, what is the function of art, and the many idiosyncrasies we follow or invent to respond to art.

The Rinehart Frames by Cheswayo Mphanza

![]()

Shangyang Fang

Burying the Mountain

Copper Canyon Press

The vase stayed empty, the sky started to rain.

My toothbrush leaned against his.

The man must be lonely, I said. No, the mountain

is never lonely. Burying my forehead inside his shoulder

blades, the mountain is making itself a man.

—from “Argument of Situations”

How it began: I didn’t have the idea of a “book” in mind. There were scattered words, and I tried to collect them. I think I always wanted to escape from the environment I grew up in. When I started running away, I started writing. I can’t tell if it’s the other way around. Poetry served as an exit, an alternative way of being alive. I was obsessed with some European modernist poets at the time; each of their poems is like a small labyrinth through which I find myself strange and elsewhere from this world. I was confounded, also fascinated. So I started writing in hopes of finding a different self at the end of each poem. This odyssey of searching for a new and hopefully truer self, has sustained my writing. This book is a byproduct of that journey.

Inspiration: Solitude has been one of the sources, and time spent with books, artworks, music. In the early years I wrote in unattended darkness. I draw inspiration mainly from different forms and modes of art—things that surprise me or confront and challenge my ways of thinking. Later, I found friends, fellow writers—conversations with Daniel Ruiz, Johann Sarna, Yuki Tanaka, and Rachel Heng inspired me. Being with them, my perceptions are constantly questioned and changed, so are my poems. Since then, my aesthetical and epistemological boundaries are shifting, permeated by the brilliance of others, like a watercolor painting.

Influences: I like artists whose work possesses the expression of tragedy at its core, a kind of es muss sein that can’t be mended. This sort of expression, to me, voices the failure of human effort, caused by humans. I often return to Johannes Brahms’s music. I’d always thought his works, despite their indisputable beauty, are dense, dark, heavy, composed with unspeakable pain and forbearance. Among all composers, Brahms is the one that took me the longest to fall in love with. It was not until I listened to his first piano concerto that I became his devoted addict. Particularly when the piano enters the orchestra after the introduction—so vulnerable, lonely, yet at the same time, formidably heroic. A paradox. Or as Mandelstam puts it, “in a slow vortex / the roses, heaviness and tenderness, in a double-wreath.” That is to say, I was influenced by the idea of paradox, which I also recognize in Franz Schubert’s and Gustav Mahler’s music. You see, I relish things that are tender, fragile, but also indestructible, like that strand of thin milk in Vermeer’s painting, a knot of the universe.

Writer’s block remedy: Usually I like to take a shower whenever I am stuck. But then I realized my hairline is receding, so I had to stop. Was it Sontag who said, “Each time I write, it’s like jumping into an icy lake”? Writing is tough work. One must take off one’s disguise, clothes. Then one must imagine the lake warm, which is against the reality. I think that poets are the obstetricians (what an odd word to my foreign ears) of poetry. Obstetric, from obstetricus, from obstetrix, meaning “one who stands opposite,” is similar to obstacle. I like this little irony—the task of poets is to bring out poetry while their stance is against it. Ego hinders the process. So, whenever I feel stuck in a poem, I try to get myself out of the way of poetry—remove the obstacle. I remain in silence and listen.

Advice: I don’t think I’m in the position of giving advice. But humility is one important lesson I learned from Brigit Pegeen Kelly. And try to write and experiment with as many styles, subject matters, and forms as you want. Follow your wildest thoughts. In one poem I wrote, “I write to make myself unrecognized.” Namelessness is an invaluable form of freedom. Since I cannot give any wise advice, allow me to borrow a few pieces from others, which I found most helpful. One is from Denis Johnson, who said, “Write naked. That means to write what you would never say. Write in blood. As if ink is so precious you can’t waste it. Write in exile, as if you are never going to get home again, and you have to call back every detail.” Another is from Tsvetaeva: “I can eat—with dirty hands, sleep—with dirty hands, write with dirty hands I cannot. (In Soviet Russia, when there was no water, licked my hands.)”

Finding time to write: One can always find time to write.

Putting the book together: I constructed the structure of the manuscript using a Chinese quatrain by Du Fu. Each line draws a specific theme based on my interpretation of the poem. So, the book has a thematic arc; the themes are, of course, fluid and intertwined throughout the four sections. When I was doing a residency at Vermont Studio Center, I printed out all the poems, pasted them on the wall, and wrote a little summary on each page—what is the subject, theme, form; what mode each poem is operating in, whether it’s lyrical, meditative, narrative, or rhetorical, etc. I also benefited from the eyes and ears of many friends and mentors before the manuscript was finalized, particularly Louise Glück, who helped to transform it at the last minute. For three months before the deadline of the final draft, Louise worked with me revising the whole book. I was asked to rewrite many poems. Some I did, some I didn’t. The whole experience was a blessing. The book wouldn’t be in the shape it is without her.

What’s next: Living. Trying to improve my soul. Finding a new self who can see differently and write differently.

Age: 27.

Residence: California.

Job: I am on a fellowship at Stanford University, but I hope to contribute to society soon, as my parents have long requested. Or not.

Time spent writing the book: Six years. I wrote the earliest poems in the book when I was a sophomore studying engineering. “Aria of an Ebbing Scene,” “Celadon,” “Utterance of a Folding Fan,” “Fish,” and “If You Talk About Sadness, Fugue” were all written at that time when my English was awfully underdeveloped. Though immature, I think now I was more untethered and interesting then. The latest poem in the book would be “Acknowledgement: Erato,” which I wrote after turning in the final draft. I thought the book wouldn’t be complete if I didn’t acknowledge those who accompanied me, or perhaps saved me, in the process of writing this piece of dark mess. I was met by the light of others.

Time spent finding a home for it: Approximately twenty days. Mainly because I wasn’t trying to publish a book. It all happened too fast, too overwhelming.

Burying the Mountain by Shangyang Fang