Last spring, Mark Adler noticed a dramatic uptick in attempts to ban books at the Paris–Bourbon County Library in Paris, Kentucky, where he is the director. Before that, library staffers fielded the occasional request for a book to be removed from shelves. But by the fall of 2023, they had already received requests to pull 102 titles from the library’s collection.

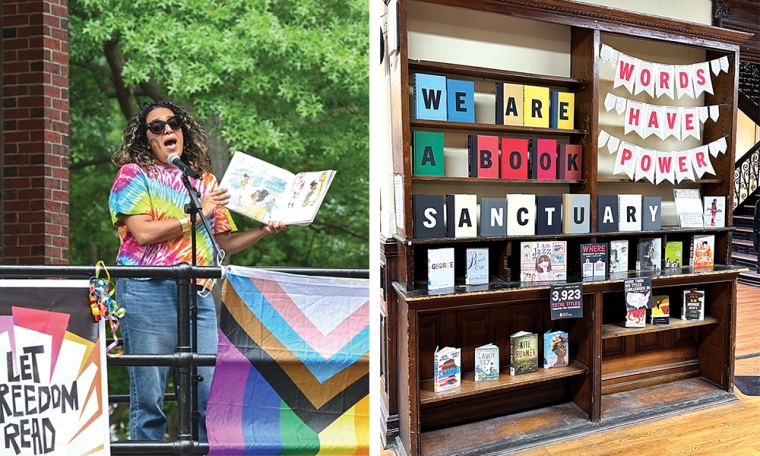

Left: Raakhee Mirchandani, an author and board trustee of the Hoboken Public Library, reads at a banned-books readathon event in Hoboken, New Jersey, in June 2023. Right: A display at the Hoboken Public Library, which in August 2023 declared itself a book sanctuary. (Credit: Left: John Dalton; Right: Hoboken Public Library)

“Watching as that progressed over the next couple of months and the toll it took on staff, that was hard,” says Adler. “And I remembered why I became a librarian, and I let myself cry. It was just this flood of tears for a few minutes, and then that was replaced by anger and indignation.”

Aware that other libraries were shouldering an increase in attempts to ban books, Adler began researching methods used to protect access to challenged titles. He discovered the “sanctuary” movement, which marks libraries and other institutions as safe spaces for books that have been targeted by activists with the aim of keeping them from readers. With his recommendation the library’s board adopted a resolution in November declaring the library a sanctuary.

The Paris–Bourbon County Library joins a growing roster of such sanctuaries nationwide, including not only libraries but also bookstores and other spaces. They are following the lead of the Chicago Public Library, which last September named itself a “book sanctuary,” promising that each of its eighty-one branches would increase access to banned or challenged books and host talks and events about diverse literature and book censorship. The library also launched a website, booksanctuary.org, inviting others to proclaim themselves sanctuaries and offering resources for doing so. More than 3,300 book sanctuaries have been established so far, according to the website.

“If people can’t be assured that when they come here they can see a multiplicity and diversity of ideas and opinions, then we’re not doing our duty,” says Adler of his reasoning for advocating for his library to become a sanctuary. Although it has chosen to label itself a “sanctuary library” rather than a “book sanctuary,” Adler says he and other staff are following the sanctuary model outlined by the Chicago Public Library.

As long as there have been folks challenging books, there have been others fighting to protect the right to read those books. But over the past several years, the need for this work has increased as national groups—including conservative think tanks, extremist hate groups, and political action committees—have fomented outrage around books and other library materials such as periodicals, DVDs, and databases, particularly those that cover race, sexuality, and gender.

The American Library Association (ALA) reported that 2022 set a record in book-banning efforts, with more titles challenged at public and school libraries than the ALA had ever recorded. Between January 1 and August 31, 2023, the ALA reported that even more books were challenged than during the same period in 2022—1,915 unique titles—with a noteworthy increase in challenges at public libraries.

As a sanctuary, the Paris–Bourbon County Library has put several measures in place that protect against such efforts. For example, the library streamlined the review policy for book challenges in order to more easily thwart what Adler described as a tactic by activists to overwhelm librarians with requests to ban books and revised the form used to challenge books to include stronger language about the library’s commitment to offering “each patron unrestricted access to a broad and diverse collection of resources.” The library is also planning to create a special display of frequently banned and challenged books, uplifting those voices that are most often silenced.

In New Jersey, the Hoboken Public Library (HPL) was declared a book sanctuary by the board of trustees last August; the library has since been working to increase access to frequently banned books and rally the community to do the same. Even before becoming a sanctuary, HPL held LGBTQ-friendly events—including children’s story hours featuring readings by drag queens—displayed books that have been banned elsewhere, and integrated frequently challenged books into its permanent collection. But adopting the official title of “book sanctuary” makes an important statement, says HPL’s director, Jennie Pu. It’s also a promise that “we’ll actively collect any and all books that are being challenged for whatever reason. We will make those available to the public. And we will put a call out [and] encourage people to do the same in their households and in their Little Free Libraries,” Pu says, referring to an initiative wherein individuals, businesses, or others collect books and make them available to whoever wants to take them.

The library staff also approached the Hoboken City Council about the city’s role in protecting access to books, and in September, Hoboken became the first “sanctuary city” in New Jersey. Emily Jabbour, president of the City Council, says she supported the resolution because it sends a message that there are places throughout the city where people can access books, from stores to schools.

Even without the official title of “book sanctuary,” free-speech advocates have found ways to increase access to titles that have come under attack by book banners.

The Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) in New York, for one, launched Books Unbanned, enabling teens and others around the country to sign up for a free digital library card that grants online access to BPL’s collection of books that have been frequently challenged or banned. Libraries in Boston, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Seattle have since followed suit with their own digital library card programs.

Over the past couple of years, librarians and others have considered how else they might fight back against book challenges. “There have been a lot of people reaching out to ask more about what book sanctuaries are, what their history is, and how they can become book sanctuaries themselves,” says Pu. “I think that is how the work has been evolving for us. Serving as a resource and support [for other communities].”

At BPL, chief librarian Nick Higgins also wants to support readers and writers beyond the library, which can’t fix the larger political problems that contribute to book-banning efforts.

Higgins likens the initial Books Unbanned program to an emergency room approach, a resource people can use when they’re at their most desperate. “But if you’re looking at it through a public health lens, what you really want to do is look at the environment that creates the situation where people have to go and use the emergency room,” he says. “You want to do everything you can to address the underlying conditions.”

To that end, BPL staffers have brainstormed ideas for how they might best support young people in the communities that are facing a lot of book bans and challenges. This has led to the formation of the Intellectual Freedom Teen Council, a group of young adults from across the country who meet regularly online to discuss book challenges, censorship, and intellectual freedom.

From library to library, across communities, no matter the approach, those who care about access to books agree: No one’s voice should be silenced; freedom of expression is vital.

“I’m just trying to remind people their rights are tenuous,” says Adler. “It’s important for them to remember what their rights are, and it’s important for us to identify strategies to make sure they continue to have those rights.”

Steph Auteri has written for the Atlantic, the Washington Post, Vice, and elsewhere. She is the author of A Dirty Word: How a Sex Writer Reclaimed Her Sexuality (Cleis Press, 2018) and the founder of Guerrilla Sex Ed, an online resource for parents and other caregivers.