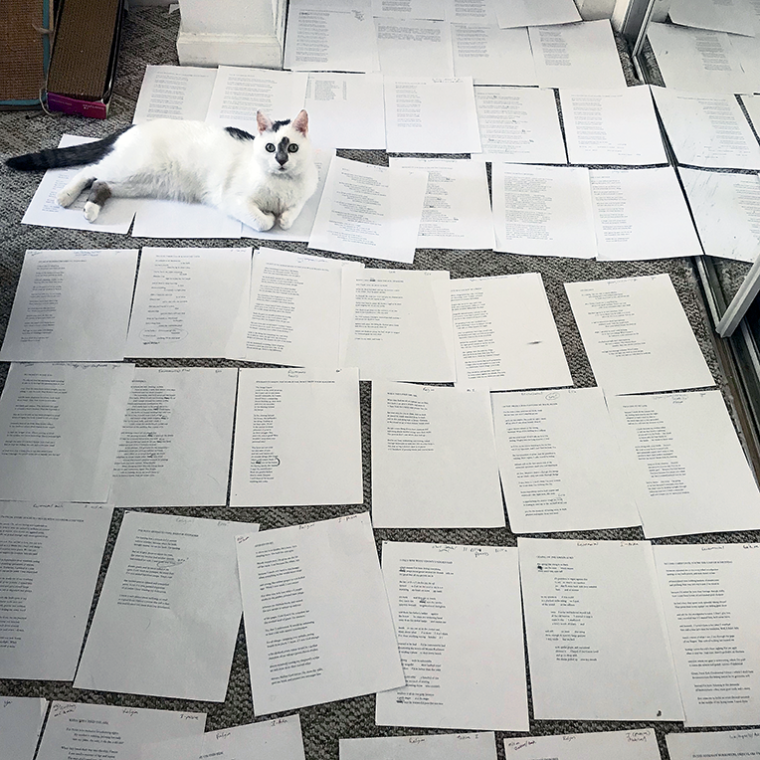

If you follow any number of poets on social media, you’ve probably seen a version of this photo: the pages of a collection in progress, spread across the floor or perhaps taped on a wall. Sometimes it’s an orderly line across the room, sometimes a flurry of printer paper, sometimes a spiral. Often there’s a cat and a joke about its editorial feedback. But what exactly are those poets doing? How does a whole bunch of poems, printed out and arrayed in space, become a book?

Paige Lewis posted this image of their cat Filfy and the pages of what would become their debut poetry collection, Space Struck (Sarabande Books, 2019), to Instagram in 2018 along with the comment, “He’s helping.” (Credit: Paige Lewis)

I’ve been obsessed with this question since the first time I tried to order the poems of a manuscript, in my final semester of college, when my best friend and I decided that the morning after we’d thrown a big party in our cheap, large off-campus apartment was the perfect moment to revise our senior theses. (I’m thankful that, back then, we did not have smartphones or social media to document the sticky cups or ashtrays we pushed out of the way to make room for the poems that stretched across the couch to the coffee table and onto the floor.) Since then I’ve published a book and a chapbook, and I’ve read for chapbook and book contests, so I’ve seen many, many approaches to making order out of the chaos of a group of poems.

The advice I’ll offer here is all underpinned by an argument that the poetry book should be more than just a shuffling-together of the best fifty or so poems you’ve written so far. Instead the poems should sit deliberately together to create a world. Together, their shared concerns, their order, and their relationship to one another make something greater than the sum of their parts.

These suggestions are meant to be generative and spur you to draft new poems and explore new avenues for your writing. If you think of your poems, whether you’ve got twenty or eighty, as the core of a possible collection, you can begin to observe how they hang together. You can write new poems into those connections, and you can also challenge yourself to draft pieces that will vary the patterns you’ve detected. In fact, the ideal time to start reading your work as a manuscript may be earlier than you think: once you have twenty or so poems, when themes are beginning to emerge, but the manuscript as a whole is still highly malleable. At that point you can start to see the shape of your obsessions and follow them to a completed manuscript.

![]()

Start just like the poets on the internet, by spreading out all your poems. What you’re aiming to do here is to see your work at a zoomed-out level so that instead of just polishing individual poems, you can notice the shape of the collection emerging.

What do you actually see when you look at your work from a bit of a distance? If you stand a few feet away from the pages, you can note formal trends in line and stanza length and visual density and space. You will be able to discern if you’ve unknowingly fallen in love with the couplet, or if you tend to end every poem just short of a page. If you get a bit closer, you can consider how you open poems, how you close them, what you do with line breaks and sentence structure, which words you repeat. Patterns aren’t necessarily a problem—in some cases they lend cohesion, as an image or form recurs throughout the book—but you do want to be sure those patterns are a considered choice and not just a habit you’ve fallen into. Repetition easily makes for monotony, unless the word or image or form carries some new weight or nuance when it recurs. (I say this as someone who had to CTRL + F to find all the times I’d used several beloved words, including tiny and rot, in my most recent manuscript and then cut all but one or two uses of each word. I recommend putting your manuscript in a word-cloud generator, which will provide a visual representation of how many times you use each word in your book.)

Color-coding can make trends and patterns visible. You can code by topic and technique, so one poem might have a red stripe for family history and also a yellow stripe indicating that it ends in a question. Color-coding like this allows you to see the number of poems related to each topic or using each technique, as well as their proximity to similar poems. You might see three red-striped poems very near one another and decide to spread them out a bit, or you might decide it’s time to cut a few when you’re wearing out the idea. You might know, for example, that you have a strong interest in Catholic doctrine and its faith in the transformative power of language and ritual—but seeing six or eight poems all bearing the same color stripe might force you to reckon with how many of those poems are necessary for the manuscript and when you might need to move on. (Does this sound like I’m speaking from experience? Louise Glück wrote in Proofs and Theories: Essays on Poetry, published by Ecco in 1994, that after finishing each book, she made herself a new set of rules for writing the next poems, such as not using first person or asking questions. This is a practice I’ve had to force myself to take up as well.)

![]()

As you look at your manuscript from this bird’s-eye view, you may also begin to see new possibilities emerge. If you’ve written one poem that is direct address, you could write another in that form, or you could write a poem in which a different speaker answers. One or more poems on a given topic could suggest a series. You could decide to write one poem to answer another, the way that, in Cassie Pruyn’s Lena (Texas Tech University Press, 2017), “Lena, No One Knew” is followed by “No One Except.” The first poem offers a look at the giddy intimacy and grief a couple experiences; the second shows the laughter and humor also inside that relationship. The tonal shift keeps the reader engaged, while the clear links between the poems show the poet’s command of her craft.

Developing a series or sequence can give your manuscript shape and coherence. These series can be scattered series, in which the sections of a long poem are broken up over the book, or stacked series, so that all the poems in a series or sequence appear next to one another. Examples of the former include Jacques J. Rancourt’s Novena (Louisiana State University Press, 2017), in which the nine parts of the title poem are spread across the book, and Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s The Last Time I Saw Amelia Earhart (Persea Books, 2005), which, in addition to the long title poem and the sonnet sequence “Circus Fire, 1944,” also includes the long poem “From the Adult Drive-In,” with its sections dispersed across the book. A scattered series often creates a narrative or formal scaffolding for the book, with an image often enriched or altered each time it returns. Analicia Sotelo’s Virgin (Milkweed Editions, 2018), in contrast, uses stacked series in four of the book’s seven sections, so that all the “Trauma With —” poems appear in the section titled “Humiliation,” and a sequence of Ariadne and Theseus poems are grouped in the section titled “Myth.” The density of a stacked series often evokes obsession or intensity. Whatever strategy the poet uses, series like this suggest a high level of care has gone into shaping the manuscript and they help the reader see the links between the disparate pieces of the collection.

![]()

As you think about patterns, sequences, and the relationships between your poems, you can also begin to consider whether your manuscript would benefit from sections. As a reader I like sections because I want to be guided; I like it when I feel a poet is helping me see which pieces should be read together and when I can take a breath before proceeding to the next part. (This can also be an argument for not having sections, as a book without them suggests a kind of unbreaking attention, perhaps obsession.) In general, numbered sections or sections broken by white space or symbols often work better than titled sections, which can feel either random or heavy-handed. There are always counterexamples, though, like Aimée Baker’s Doe (University of Akron Press, 2018), which documents the stories of missing and unidentified women and groups those poems into two sections, simply titled “Missing” and “Unidentified.” Baker’s book also shows the power of formal variation; though the content is relentlessly dark, the variety in approaches and forms makes each poem feel fresh and the loss of each woman freshly horrifying. Oliver de la Paz’s The Boy in the Labyrinth (University of Akron Press, 2019), which portrays the experience of parenting two neurodiverse children and imagines how those children experience the world, uses the structure of Greek tragedy and conveys that form through its section titles, beginning with “Credo” and moving from “Prologue” to “Strophe,” “Antistrophe,” “Epode,” and “Coda.”

The table of contents can also be a useful tool for examining the breadth and coherence of the collection at a high level. When you skim your table of contents, you can identify trends or weaknesses in your titles. Titles that are fine, if not terribly effective for individual poems, will show themselves as weaker when forced to stand on their own in the table of contents.

The table of contents of a well-crafted manuscript reveals the contours of the particular intelligence at work in the book. The one in Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018) quickly communicates how sharp the poet is and how much will be expected of the reader. The use of the book’s title as section titles (“I Can’t Talk,” “About the Trees,” “Without the Blood,” followed by an epilogue) suggests a certain obsessive insistence on that image of racialized violence bursting out from the pastoral. In the poem titles you’ll find references to Phillis Wheatley; a sequence of poems titled “After Apollo,” “After Agon,” and “After Orpheus,” which the end notes indicate are ballets; “The Rime of Nina Simone” with its allusion to Samuel Taylor Coleridge alongside the legendary singer; and “BBHMM,” a reference to Rihanna. In short, this is a poet who’s widely read, with a rich set of interests and influences, from literary history to the arts to pop culture. The poet expects a lot from her reader, and the table of contents promises that close reading the work will be worth it.

Try this out for yourself: Take a beloved book of poetry off your shelf, and flip to the table of contents. What is the overall shape of the collection? What do the titles suggest about the themes, forms, and obsessions of the book? What does the book expect of you? How does it invite you in or maybe challenge you?

Now consider your own table of contents. What kinds of predictions and expectations would a reader have, looking just at your titles, the sequence of poems, and your use of sections?

![]()

Once you’ve done a high-level read of your book, consider how it will open. A common strategy is to start with a short, loud poem, one that will get your readers’ attention and persuade them to keep reading. (The contest system, the mechanism whereby many first books of poetry are published, also encourages poets to use this strategy. Going big at the beginning can feel like a way to propel your manuscript out of the slush.) Rebecca Hazelton’s Gloss (University of Wisconsin Press, 2019), which opens with the funny and tender poem “Group Sex,” uses this strategy. The poem turns out not to be about an orgy (sorry), and the opening lines establish the premise better than I can: “There’s you and your lover and there’s also his idea / of who you are in this moment, and your idea of who / he should be, both of these like both of you but better—.”

Although a short poem can quickly engage readers without overwhelming them, you might opt to start with a longer poem. In an interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books blog, Jenny Molberg, who directs Pleiades Press, observed that she frequently sees long poems buried three-quarters of the way through the manuscript, which is where a reader’s attention is likely to be lowest. Her own first book, Marvels of the Invisible (Tupelo Press, 2017), begins with the long poem “Echolocation,” and Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead (Graywolf Press, 2017) and Gregory Pardlo’s Totem (American Poetry Review, 2007) both also begin with a long poem. Opening with a poem that asks a significant intellectual and emotional investment from the reader can establish the book’s stakes and expectations right away. (If you’d like to read more about how poets select an opening poem, Sarah Blake’s series for the Chicago Review of Books covers this, and another installment in her series includes several poets discussing how they chose the last poem for their book.)

Beyond thinking of the first poem, though, I’d suggest you carefully craft an opening sequence. The move from the first to the second poem is especially vital, as a place to show your range as a writer. Camille T. Dungy’s Trophic Cascade (Wesleyan University Press, 2017) includes an especially skillful opening sequence, which moves from the narrative poem “Natural History” to the brief lyric “Before the fetus proves viable, a stroll creekside in the High Sierra” and then on to the fragmentary “still in a state of uncreation” and then the prose poem “Ars Poetica: Mercator Projection.” The poems are bound together by their attention to the natural world and themes of family and motherhood, but they vary in their mode and form, showing the range of the book. Cortney Lamar Charleston’s Telepathologies (Saturnalia Books, 2017) also uses formal variation in the opening sequence, as the book moves from the visual and sonic density of “How Do You Raise a Black Child?” to the couplets and more narrative movement of “Pool Party” and on to the tercets and anaphora of “Blackness as a Compound of If Statements.” Again, the opening poems establish the central themes of the book, and the formal variation showcases the poet’s craft and breadth of technique.

![]()

Now that you have established the flow and structure of the manuscript, you can go back to working on the individual pieces. You can make a list of assignments, from cutting repetition and coming up with new titles to changing the form of a few pieces and writing new poems. Ask yourself how the poems you’ve written suggest more to come—and how, especially, you can enrich and complicate what you’ve written so far with new poems. If you’ve developed patterns with respect to form or technique, consider how you can either lean into those patterns or break them with new poems that show your range. The poems you’ve already written can point you toward new work.

Individual poems were what first drew me to poetry, but in the years since then, I’ve become convinced that the book is an essential unit for poetry. A well-crafted book allows us to engage deeply with another’s intelligence and imagination. Individual poems, when placed together in a collection, can generate new heat as a word or image returns and carries with it the echo of its previous use, or as a title or form challenges a settled expectation. The strategies I’ve offered here can lead you toward shaping your own poems into a cohesive book—one that, like the collections I love best, is an immersive experience for the reader.

Nancy Reddy is the author of Double Jinx (Milkweed Editions, 2015) and Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press, 2018) and the coeditor of The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood, forthcoming from the University of Georgia Press in November 2021.