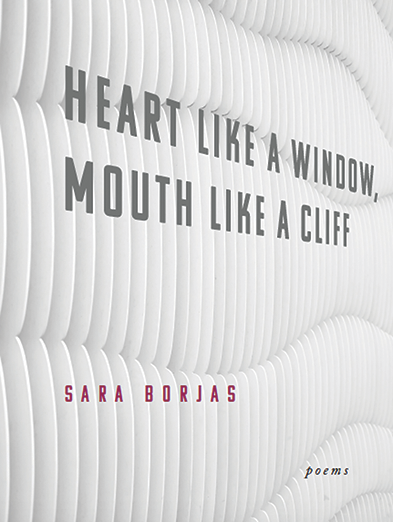

Sara Borjas

Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff

Noemi Press

I am the scrape of the lowrider as it exits the driveway,

bothering the neighbors.

—from “Ars Poetica”

How it began: In my heart I wanted to love better. We are a colonized people putting ourselves together for hundreds of years. Much of our lives, ideas, values, and traditions are survival tactics. I wanted to see my parents as individuals but also through this lens and love them wholly. I didn’t want my heartbreak, or theirs, to be for nothing. So in each poem I asked: How am I making myself and my family more simple and responsible for our lives than we actually are? And I never really stopped answering, even through all the revisions and drafts, and even now. Many of these poems are me puzzling together how I show love and what and who I think deserves it and why. When I began working with Noemi, one of the first things my editor, Carmen Giménez Smith, told me was that I had a manuscript but not a book yet. This stands out as the beginning for me. This is when I felt for real compelled, capable, and honestly challenged to write this very specific collection.

Inspiration: Oldiez. Fresno. The reliability of crop rows and how you can see all the way to the end no matter what. Books like Whereas by Layli Long Soldier, Crush by Richard Siken, Blood by Shane McCrae, and MyOther Tongue by Rosa Alcalá; Anne Sexton; Rumi; “punk poetics,” as Juan Felipe Herrera says; the word no out of any woman of color’s mouth; Lifetime movies; Real Housewives; really, any drama where the protagonists are women; oranges from my dad’s tree and zucchinis from his garden; my mom’s sense of humor; all shit-talkers everywhere; my sister’s ruthless sentimentality and her writing—she’s an amazing writer but stays low-key; and watching and helping my friends work on their books at the same time.

Influences: Roque Dalton for his sentimentality coupled with self-ridicule and the tendency to exaggerate, Richard Siken for his associative genius and how he writes about love, Dulce María Loynaz for showing me that my parts equal a center and are not scraps, and No Doubt for showing how to make fun of the patriarchy. All these artists showed me how to be extra and be beautiful in it.

Writer’s block remedy: When I reach an impasse, I accept myself and treat it as a liberty. I don’t feel the need to keep going if I’m not excited about writing. I think that’s always bothered me about the possibility of becoming a writer, that I’m expected to produce writing. It feels very capitalist and very colonial to make any part of myself or my behavior a commodity. I try to break the habit by being okay with not writing. I watch TV and films, talk to my friends and family, read, watch shows about outer space, and go down rabbit holes looking up phenomena. I cook. And all that, to me, is a making.

Advice: Write toward honesty, then, really write toward honesty. Stop lying. As Bruce Lee said: “It is easy for me to put on a show and be cocky…. I can show you some really fancy movement. But to express oneself honestly, not lying to oneself—that my friend, is very hard to do.”

Finding time to write: Right now I have a dream schedule that creates an alternative problem of when not to write. However, I am not someone who can sit down and write like it is a job, which I am cool with. So I find time by reading and getting pumped about what others are thinking, asking, and their work leads me to writing. I’m an impulsive, and honestly, kind of dramatic, person, and my writing habits are equally volatile. If I’m feeling, it’s always deeply. If I’m writing, it’s always obsessively. I know this will probably be the only time in my life when I have this time, and I feel a pressure that accompanies that privilege, but I also feel really free.

Putting the book together: I cannot stress how crucial editors are. Editors make the poetry world go ’round. For a few years, I maneuvered papers around my bedroom floor, as poets do. But when I became strategic, it was because my editors challenged me. The poet Ángel García charged me to organize the book according to theme and that’s how I found imbalances in the narrative. My friend Julia Bouwsma, who was a hero in helping me make this book, said, “You can have a narrative without a narrative structure.” Her comment freed me. Carmen Giménez Smith did not let me get away with shit. One day she called me and said, “You wrote ‘heart’ seventeen times in this book,” and hung up. I needed to be checked, and she was really good at holding me accountable. Blas Falconer, in the kindest way, showed me where I was circling the wound, peeking all around it rather than through it. J. Michael Martinez pushed me to think about form, marginalia, the reader’s way of participating, and the kind of double consciousness that was at work in my speaker’s voice. Ultimately, I wrote new work, and mostly rewrote, sometimes entirely, whole poems. I consolidated poems. I wrote an essay called “We Are Too Big for This House” and stuck it near the beginning to explain why the speaker is so resentful and still so tender. I used the myth of Narcissus to say things I couldn’t entirely own. At a point I decided I was done. And I accepted it.

What’s next: I’m writing new poems; working on lyric essays; trying to organize readings for poets in Los Angeles when I can alongside Joseph Rios; creating my courses without fear of being fired for the first time; learning to walk away, to eat healthier, to prioritize my heart as much as my body and mind; and growing food and parenting plants.

Age: 33.

Residence: Leimert Park, Los Angeles. But I’m from Fresno, California.

Job: I teach creative writing at UC Riverside and moonlight as a bartender.

Time spent writing the book: The oldest poems in the book are eight years old but are wildly different. The only thing holding them is the memory or the first draft and the essential question I had and that I can still sense in their revised forms.

Time spent finding a home for it: About three or four years. In 2014 I was a finalist for the Andres Montoya Prize, and that’s when I started taking my poetry more seriously. Since then I reworked it until I was offered a contract by Noemi in 2017—the year the real writing began.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Why I Am Like Tequila (Willow Books) by Lupe Méndez, Careen (Noemi Press) by Grace Shuyi Liew, Bicycle in a Ransacked City: An Elegy (Alice James Books) by Andrés Cerpa. All fire. All so honest.

![]()

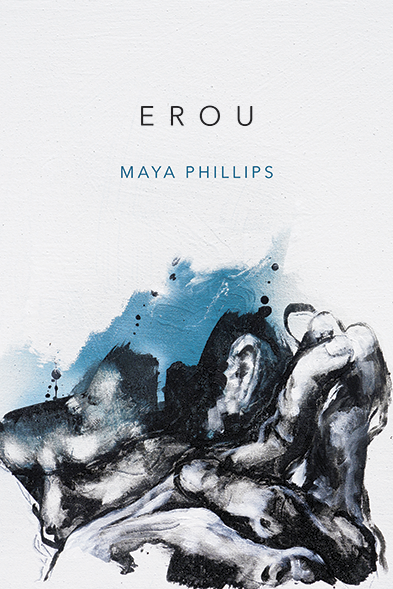

Maya Phillips

Erou

Four Way Books

Erou born in the county of Kings

raised in the lap of Queens

sitting on the throne of his mama’s front stoop

Isn’t this how an Erou begins?

—from “Erou 1”

How it began: I’ve always been obsessed with mythology, and for years I knew I was, at some point, going to start writing about my relationship with my dad. It was a topic I kind of wrote around for a while, but our relationship, and the complicated ways that my family worked and related to one another, obviously had a deep impact on me. He died in 2014, and in those next few months I started writing about him but knew I needed some help shaping the work and the project, because I had been feeling a bit untethered from my work for a while. I started my MFA program, at Warren Wilson College, in 2015, and I wrote this collection almost wholly in that two-year period.

Inspiration: Mythology certainly. In particular, Greek myths, the epics, but I’ll broaden it and also say any kind of mythology or fairy tale or fanciful story in which there are heroes and villains and gods and quests. I like that sense of scope, of the largeness of humanity, and, beyond that, of some version of god, some kind of agency of fate. And visual art. Any kind of work that makes me experience something on a visceral level, and, because I think I must be a masochist, I particularly enjoy art that makes me feel sorrow or loss in a way that’s new and interesting and complex.

Influences: Anne Carson, for all of the ways she uses language. I’m talking about her poems but also her works of translation—she has such a rich understanding of language and there’s a cool kind of labyrinthine way that her poems work themselves out, like you can see the workings of her mind behind them, and it’s brilliant. Patricia Smith and Rita Dove were both influential in how I thought about these poems. I was introduced to Patricia’s work when I was in undergrad and had just discovered slam poetry. I heard her read in a dive bar in Cambridge and was stunned by her use of metaphor and how exquisite her sense of voice was. I spent several years writing toward her. And Rita Dove’s poems, particularly the ones about her parents and the Demeter and Persephone poems, helped me think about how one can mythologize family and relationships. And Louise Glück is a poet I admire for her spareness and thoughtfulness and use of white space. When I feel too bogged down in my own wordiness—which happens quite a lot!—I think of poets like her, how her poems feel light and airy and yet still so rich and substantial, like they’re whittled down to the most essential bits.

Writer’s block remedy: I panic a bit, honestly. I’m very hard on myself and struggle a lot with anxiety, so creative blocks are tough. I usually just try to push through, but if that doesn’t work, I try switching to another form of writing—there’s always a new article or review to write. Or I might try an essay or fiction or a play or something. Or I’ll just switch to another poem. I pace a lot when I’m stuck with poems, say the words aloud over and over again and try to let the sounds lead me somewhere new, because sounds and rhythms are really important to my work. I go from one room to another or just change seats to kind of trick myself into getting into a new headspace. A walk is usually my last resort—but sometimes that does the trick.

Advice: I’d probably say to be bold. Experiment with your work, and don’t edit out all the fun and the strangeness and the wonder. It’s so easy to get burnt out looking at the same poems over and over again and scrutinizing this manuscript that you want to be perfect, but I think the hardest part of being a writer is figuring out when you can trust that critical voice in your head and when you need to tell it to shut up.

Finding time to write: Though I’m a very A-type person overall, and I do think I can be fairly prolific, I don’t consider myself the most disciplined writer in that sense. I pretty much write when I feel like it. Sometimes I’ll go through periods where I sit myself down and make myself write every day, and those periods are always productive but draining. Doing an MFA while working full-time and freelancing really kept me regimented, but, again, I felt burned out after a while. But now I write when I decide to, sometimes in the evening, sometimes in the morning, sometimes at a random point in my day when a thought just occurs to me on my way to work or whatever. Between my journalism, poetry, and other creative writing, I’m always working on something. It’s just a matter of juggling them—that’s the real struggle.

Putting the book together: I love structure and order—I’m such an A-type—so I knew that I was going to use my central poem, “Erou,” my version of a contemporary epic poem, as the spine of the collection. “Erou” goes through the life of the main figure, the father/husband, from birth to death, drawing on tropes and symbols and patterns from the hero’s journey in various myths—the stories of Odysseus, Aeneas, Jason, etc. The tricky thing was figuring out how to interweave the other threads and how to introduce other characters and make sure that the narrative made sense. My MFA thesis adviser, Gaby Calvocoressi, who’s amazing, suggested that I group sets of poems together to make mini-arcs, which I did, and then I strung them together in and around the sections of my central poem. I made index cards for all of the poems, with the title, first line, and last line, and spread them all out on a table and just swapped them around, with the full poems handy nearby for reference, for the repeat images and themes and characters mentioned in the poems proper. I actually enjoyed that part, finally having the whole story there but just trying to decide how to tell it. It was like doing one of those big puzzles, but I could change the pieces to fit together in different ways to reveal the picture I wanted.

What’s next: Ugh, a bit of everything! I tend to overdo it, so I’m always working, or at least trying to work, on several things at once. There’s my culture writing, and I’m working on poems for what will be my second book. And then I’ll make various attempts at writing in other forms and genres if I’m feeling particularly daring.

Age: 29.

Residence: Brooklyn, New York.

Job: Copy editor/web producer/contributor at the New Yorker and a freelance culture writer.

Time spent writing the book: About two to two and a half years.

Time spent finding a home for it: Three weeks. I know that isn’t typical, and I feel so fortunate that this is how it worked out, but I had a list of publishers I knew I wanted to submit to, and I sent the manuscript to Four Way first and heard back less than a month later. I was pretty floored—and thrilled.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Hard Damage (University of Nebraska Press) by Aria Aber and Invasive species (Nightboat Books) by Marwa Helal.