In August, Carmen Giménez began her work as Graywolf Press’s new publisher and executive director, succeeding Fiona McCrae, whose tenure spanned twenty-eight years. Founded in 1974, Graywolf Press has published some of the most acclaimed and beloved writers in recent memory: Percival Everett, Claudia Rankine, Diane Seuss, Solmaz Sharif, and Tracy K. Smith, as well as Giménez herself. A recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and Academy of American Poets, Giménez served as Noemi Press’s publisher for twenty years, editor in chief of Puerto del Sol, and poetry editor of the Nation. She is the author of eight books, most recently the poetry collection Be Recorder (Graywolf Press, 2019), a finalist for the National Book Award. Giménez recently discussed the shifting landscape of literary publishing, her multidisciplinary career, and what collaboration means to her.

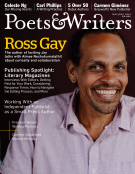

Carmen Giménez, the new publisher and executive director of Graywolf Press. (Credit: John Gardner)

What excites you about your new role?

What’s exciting is that it’s absolutely the authors who make the list, but it’s also the collaboration with our editors, who are brilliant, not only in terms of the titles they acquire, but also the ways in which they bring a manuscript to life in the book, its final iteration. That to me is very exciting—the vision of putting together a list that’s eclectic and dynamic and interesting and surprising. And then you have these amazing books that in many cases have changed the way we think about what a book can do, have been enormous influences in the literary world, and have brought important attention to authors doing exciting work that might not be accommodated by a commercial press.

How has your work as a poet, memoirist, editor, educator, and translator informed your leadership style?

One of the advantages I have as an author is that I know what it feels like on the other side. And obviously being a writer requires being a reader. And I’ve been a very expansive, inclusive, wide reader, which I think is also vital to this type of role.

I think the notion of leadership is important, but what’s most important about being in the literary community is collaboration. And that’s what I love about Graywolf. There’s a lot of collaboration and interaction and cross-pollination among the different teams that work here. I’m very interested in how all the sorts of collaborations that I’ve had are going to serve as a backdrop for how I approach the work that I do.

Would you walk us through a day in your life at Graywolf?

An important part of my job is development—fundraising for the organization and just creating an awareness that this is a nonprofit, and part of its success relies on people out there believing in the mission and the work that we’re doing. Meeting with our development team—talking about how to approach things, how to create events or circumstances in which we can cultivate new donors—is part of it.

We’re really paying attention day by day to how a book is doing in the world. We have a fantastic marketing team that keeps us apprised of where the book is going, who’s looking at the book, how the book is selling. Then there’s the editorial piece. There are stages in which marketing and editorial intersect. There are stages in which we’re looking at the list as a whole and seeing: What does it look like? What is it going to look like? What is the balance? What does each book do or say? And what are the gaps in the list?

Not only that, but we also are anticipating the books that may cross our paths. Just in my first two and a half weeks, I’ve been reading tons of galleys and published books just to get a sense, just to get acculturated. And I imagine that’s going to be a big part of it. I’m not currently editing any books, but that’s definitely in the future.

There’s also the day-to-day, thinking about how people work together. I really want people to be happy working here. I want to create a climate in which people feel they have agency and there’s a dynamic in which they feel satisfied in the job that they’re doing and can grow in the position they have. A lot of it is sitting back a little bit and taking it in and then trying to respond to whatever it is that you see.

I think the advantage is that I’m coming in with new eyes and am able to see what’s possible, but I’m also not going to knock the table down or anything like that. So it’s also managing my own expectations about what I can and can’t do, what I can and can’t bring to the list, where I am in the dynamic so that people are able to thrive.

You’ve worked in literary publishing for two decades now. What first drew you to the profession?

When I was in high school, I was on the school paper, and I thought that I wanted to be a journalist. It was very exciting to me, and I liked the writing. I also liked laying out the headlines. My first couple of years were without computers, so we’d type [the text] and then we’d have to cut it with an X-Acto. And I loved that. I loved thinking about how to compose a page.

When I was in college at San José State University, I was on the literary journal there, and I was also an assistant for the university’s Center for Literary Arts. And so that just connected me. It’s like drama: There are the actors, and then there’s the tech crew. And I was just as interested in what the tech crew and the production crew were doing as I was in what the actors were doing, and that never went away.

I think that at a certain point in the early aughts, there was just such an interest in zines and chapbooks. That world of the ephemeral book was so prevalent, and I was absolutely seduced by it. And so it was the combination of this desire to have a granular relationship to putting text into the world combined with the sense of being the stage crew of the literary world—and all of that then converging. That’s how I became interested in literary editing really.

How have you seen the industry change?

When I started Noemi Press there weren’t that many presses that were mindful of publishing people of color, and it tended to be very siloed or: “We have our one person of color on our list.” I think that the landscape has transformed in that regard; lists are robust and they’re complex. They’re not perfect, but there’s much more awareness of the tapestry of brilliance that exists in the world beyond cis white men and women. I think that’s a really significant evolution. And there’s still work to do. I would say, for example, translation tends to privilege Europe and, to a certain extent, Latin America, but there are all of these places where work isn’t being translated, isn’t being represented.

What I love, and what you’re seeing so often [now]—in work like Courtney Faye Taylor’s, Anthony Cody’s, and books that we published by Joshua Escobar at Noemi Press—is thinking about the book as a visual space. It’s not just text, text, text. It’s thinking about collage, archive, typography, the page as a field. Partly I think this has happened because you see more cross-disciplinary writers entering the world of poetry, but it’s also because we live in a graphic age. Everything we’re experiencing on the screen has complexity, and we’re bringing that complexity onto the page. And so that’s a really exciting development that I’ve seen take place.

You’ve been instrumental in establishing, shaping, and sustaining many poets’ careers—among them such accomplished poets as Lillian-Yvonne Bertram, Carolina Ebeid, and Khadijah Queen. Do you believe literary publishers have any duty to showcase emerging voices? How do you balance supporting new talent and sustaining careers?

In many ways Noemi Press has been a launching pad for a lot of great writers. And they’re writers who’ve already had some things happening to them, and with the unique attention that Noemi Press has had, it’s given them space to flourish.

Noemi has acted, especially in its early years of establishing writers and addressing that issue, in a manner that larger presses, for any number of reasons, might not be able to—taking risks on books that might not sell hundreds or thousands of copies. How else are we going to change the face of literature if not to take risks on writers who are doing things that are exciting, that haven’t been seen yet, or don’t exist, or who aren’t famous on Twitter?

There is a responsibility there, and that’s one way literature has changed in the past ten or fifteen years. More presses—and I would definitely include Graywolf in that equation—have taken risks on books by first-time writers who have gone on to be enormously important and successful. But there’s also a space that needs to be made for writers’ second books, third books. Absolutely. And I’ve been thinking a little bit about this in terms of fiction, in relation to poetry not versus poetry: Writing a novel or a collection of short stories takes a really long time. Sometimes it takes five years, sometimes it takes ten. And it is not to minimize how much work it takes to write a collection of poetry, but people write collections of poetry a little bit more frequently. So that is a question of capacity. Where do those second, third, fourth collections go? It is definitely a balance of making space for those important emerging writers but also supporting the evolution of someone’s career—because sometimes the second or third or fourth book are when things really start happening or cooking.

In an era filled with sprawling novels and a well-known public appetite for protracted narratives, why might it be important to make space for literary forms that rely on brevity, in part, for their structure and effect? Could you talk about Graywolf’s relationship to the compressed forms it has championed from the beginning—poems, short stories, and essays?

Graywolf is an independent, nonprofit press that’s not totally reliant on sales. It’s supported by an audience who sees the vision of supporting writers who may not find a home with a commercial publisher because they’re not going to sell a million copies of a book. This enables us to publish things that are too risky for a commercial press to publish. And whether it be visual poems that have collage in them or collections of short stories or books that are about weird subjects that people wouldn’t necessarily know that they wanted to read about, we have the capacity to share those with the public.

But the paradox of that is that the books do sell well. There is an audience out there who is interested in the books. That really speaks to the visionary work of the staff here, also to the fact that readers are far more curious and excited and willing to take risks with texts than what commercial presses are maybe able to capture.

Our supporters allow us, as a nonprofit, the financial space essential to take those risks, which are vital. And because of that support, books like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric exist in the world. There are so many books that might not have found their way without the support we can leverage as a nonprofit.

What are your hopes for Graywolf?

The press is so successful at creating a dynamic list. I’m just a new voice who comes from a smaller—I want to say scrappier—press, and I want to bring that sense of finding possibility in books that are a little bit more raw. I do think that Graywolf does that work, but being a new voice in the conversation is going to be useful and is, I feel, part of the reason that I’m here.

I’m also interested in how Graywolf could reach a wider, more inclusive audience. And I suspect that all presses are thinking about that because the world is changing, the demographic of readership is changing, and what people want to read is also changing. Being responsive to and aware of those cultural and literary shifts is going to be an important part of my job.

Devon Walker-Figueroa is the author of Philomath (Milkweed Editions, 2021), a winner of the 2020 National Poetry Series.