This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Aaron Robertson, whose nonfiction debut, The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The book is a lyrical meditation on how Black Americans have envisioned utopia and sought to transform their lives, from Robertson’s ancestral hometown of Promise Land, Tennessee, to Detroit, the city where he was born and where one of the country’s most remarkable Black utopian experiments got its start. Founded by the preacher Albert Cleage Jr., the Shrine of the Black Madonna combined Afrocentric Christian practice with radical social projects to transform the self-conception of its members. Alongside the Shrine’s story, Robertson reflects on a diverse array of Black utopian visions, from the Reconstruction era through the countercultural fervor of the 1960s and 1970s and into the present day. Publishers Weekly called The Black Utopians “ambitious and captivating” and praised Robertson for painting “a vivid and beguiling picture of the indomitable human yearning for a safe and nurturing home.” Aaron Robertson is a writer, translator (from Italian), and editor at Spiegel & Grau. He has written for the New York Times, the Nation, Foreign Policy, n+1, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications. His translation of Igiaba Scego’s novel Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019) was shortlisted for the 2020 PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award. Robertson served as one of the judges for the 2024 International Booker Prize.

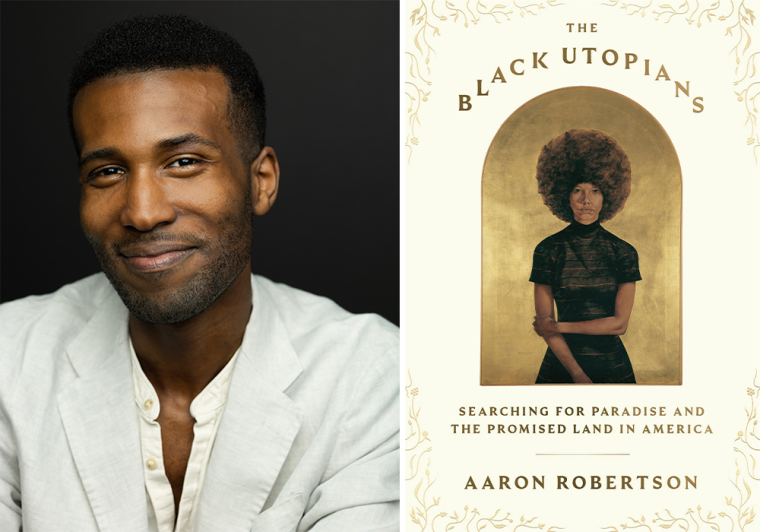

Aaron Robertson, author of The Black Utopians. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write The Black Utopians?

A little more than two years, from fall 2021 to fall 2023. The book idea came out of two essays I’d published in the Point magazine in 2020, during the George Floyd protests and the first COVID wave. And although I got the book deal right after the election that year, I wasn’t able to access any of the archives I needed for about ten months because of the pandemic. So, I ended up doing as much reading and as many interviews as I could in the meantime. By the time I finally sat down to start writing the book (I remember I was back at my mother’s home in Michigan, sitting in a backless seat at the kitchen table) I felt like I had too much to say. After I turned in the first draft, my patient editors agreed.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Two things immediately come to mind. Firstly, I didn’t really have access to the family of Reverend Albert Cleage, Jr., the Black nationalist pastor who is arguably the beating heart of the book. It’s certainly not for lack of trying! I would’ve loved to speak with his two daughters, especially Pearl Cleage, who is best known for her work as a playwright and author. In a way, the family’s wish not to participate was probably a blessing, despite my initial despair. I wanted this to be a book about communal movements across time rather than one man’s accomplishments. To learn about the kind of person Rev. Cleage was outside of the books, articles, and dissertations that were written about him, I had to rely on the personal testimonies of current and former members of his church, as well as a handful of other people who had crossed his path. There’s always a chance that memories of a beloved, deceased leader will obscure more than they reveal, so I sometimes just had to remind myself that I wasn’t writing a Great Man biography. It was more important for me to understand why the people who knew Rev. Cleage were so transformed by his work.

The other great difficulty I faced still makes me insecure. I am not a Black Christian Nationalist. Although I was raised in Christian churches, I have never been a member of the Shrine of the Black Madonna. While writing this book, I was acutely aware that the Shrine has long had its own “at-home ethnographers”—researchers who had written about the church and were organic members of the community. I had to gain the trust of every person I spoke with, or at least not attract their ire, and I think part of that work meant proving my bona fides: I was Black, I was from Detroit, I was intimately familiar with Christian traditions. I also never intended for this book to be a “comprehensive” story of the Shrine. Rather, the book had other aims. I wanted to situate the Shrine’s story in a broader history of Black utopian desire—that is, the endlessly innovative, often anti-establishment attempts to transform the world so that it is easier for Black people to find peace in it.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I am a scattershot writer. Sometimes I feel like I rarely write. I was recently commiserating with someone who, like me, had once dipped her toe into breaking news journalism. There’s a reason it didn’t work out for us. It frays the nerves and demands too much, too soon! I barely lasted as an op-ed columnist for my college newspaper because I realized I didn’t have all that much to say at the time.

Apart from The Black Utopians and the little journalism I did years ago, most of my writing happens in the margins of books that I’m reading. Usually these books, whether fiction or nonfiction, are somehow helping me think about a future project.

When I’m able to focus on writing for a prolonged period, I’m usually working at my home writing desk, on the floor, on the couch, or on the subway (rarely). I can’t work in libraries because I fall asleep in them. Unfortunately, slivers of ideas for scenes often come to me while I’m in the restroom, or otherwise indisposed and without access to my notes app or a scrap of paper.

4. What are you reading right now?

A gripping work of legal history, essentially, that comes out in early 2025 from Farrar, Straus and Giroux: Michelle Adams’s The Containment: Detroit, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for Racial Justice in the North. It is big, and it’s superb. Adams is a Detroit-born legal scholar based at the University of Michigan, and she’s writing about the 1974 Supreme Court case Milliken v. Bradley. The case was about desegregation in the North; the question was whether courts could order the implementation of desegregation plans across school district lines (in metro Detroit, in this specific case). Simply, the answer was no, unless it could be proven that school districts had intentionally segregated students.

Milliken v. Bradley, which plays a small but important role in my book, was the death knell for liberal hopes that Brown v. Board of Education would lead to true integration around the country. Schools and neighborhoods would largely remain segregated. This is still true today. Michelle and I have the same editor at FSG, Alex Star. In a way, Michelle’s wonderful book is part of why I ended up at FSG. Albert Cleage, Jr. plays a big role in The Containment. By the time Alex read my proposal, he was already familiar with Cleage because of Michelle’s work and wanted to learn more about him.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Leon Forrest. He was a Chicago-born novelist and professor. I can’t express how much his books mean to me. Everyone should read Two Wings to Veil My Face (1983), at least, which is in the running for my favorite book ever. Toni Morrison was his editor at Random House and thought he was tremendous. Luckily, Northwestern University Press recently reissued Forrest’s most famous book, Divine Days, a 1,200-page opus about an aspiring playwright on the South Side of Chicago. Forrest explicitly wanted to compete with James Joyce’s Ulysses. No one that I’ve read has so movingly and ambitiously merged African American folklore, classical mythology, and modernist techniques as well as Forrest did.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Nothing surprising here—fear. Besides the usual stuff about fear of failure, I also know that I tend to procrastinate most when I’m feeling really good about where I’m about to go with a scene, chapter, or idea. It’s strange, like a dragon sleeping on its hoard of (supposed) gold... I think I do that because I know, once I start writing, I’ll become obsessive and sort of shut the rest of the world out, which is not really a good thing to do. For the most part, though, I’ve learned to interpret my worst instances of procrastination as a good sign.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

After reading an early draft, my agent was surprised that I hadn’t brought more of my own perspective into what was clearly a personal book—one side of my family traced its roots back to a post-Reconstruction, all-Black freedom settlement in Tennessee, a utopian colony. Not to mention I was from Detroit, like so many people who joined the Shrine. Bring more of yourself in, my agent advised, as did the small group of friends who were my earliest readers (and best, most generous critics). I think it is very difficult to write about oneself in an interesting way for the duration of a book. The Black Utopians is more history than memoir for a reason, but I do think I ended up offering more of myself than I initially thought I would.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Black Utopians, what would you say?

Don’t let your research write the book for you. You’ll write a book that you’re proud of, regardless of what happens next.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Black Utopians?

I’ll mention two things: the galvanizing collective energy of Afrofuturists in Detroit—individuals such as the organizers Ingrid LaFleur and Bryce Detroit, the musician Onyx Ashanti, the writer Zig Zag Claybourne—and the deleterious “ruin porn” produced about Detroit in the late 2000s by photographers such as Andrew Moore, Yves Marchand, and Romain Meffre. The work of the former group in many ways responds to (and will hopefully outlast) the work of the latter.

Not long ago, I returned to an essay I’d written for my college literary magazine about people’s fascination with sites of ruin. The frustration I felt back then persists. Most popular visualizations of what Detroit is are not only simplistic and ill-informed but also very often dangerous to Black people who have lived there for a long time. Back in 2016 I met and reported on some of the counter-narrators who are, I think, architects of Detroit’s creative future. These kinds of creators and designers have always been in Detroit. There’s some kind of continuity between their countercultural work today and the work of their spiritual forebears in the 1960s, and even the 1860s.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

This was directed at me: Trust yourself enough to know that you don’t need to do backflips for your readers on the page. Just walk straight ahead.