This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Dara Barrois/Dixon (formerly Dara Wier), whose poetry collection Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina is out today from Wave Books. “[T]here are so many kinds of us / coming in various versions of ourselves,” she writes in the poem “Capitalism,” and it is to these various versions of ourselves that the poet applies her characteristic honesty and curiosity, reflecting on the self—as well as animals, books, skyscapes, movies, poems, other human beings—in songs of “love humor despair loving kindness love humor empathy / humor joy sympathy love kindness courage.” Dara Barrois/Dixon (formerly Dara Wier) is the author of numerous collections of poetry, including In the Still of the Night (Wave Books, 2017), You Good Thing (Wave Books, 2013), and Selected Poems (Wave Books, 2009), among others. She has received awards from the Lannan Foundation, American Poetry Review, the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. She lives and works in factory hollow in Western Massachusetts.

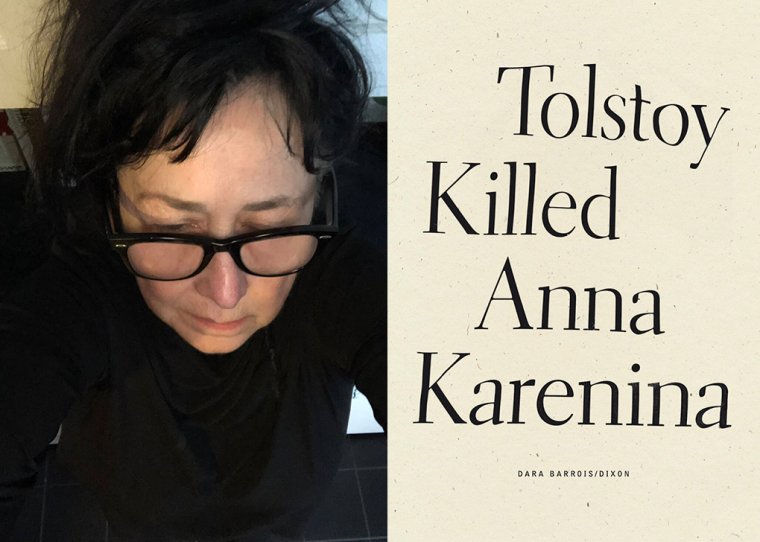

Dara Barrois/Dixon (formerly Dara Wier), author of Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina.

1. How long did it take you to write Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina?

It’s usual for me to be writing more than one book at a time; my guess is Anna’s book unfolded over the course of around five to seven years start to finish. When I write a poem I’m not necessarily thinking of it as a poem for a certain book unless I’m working in a form (e.g. Reverse Rapture’s nine-line, nine-stanza poems; in progress since 2020, something I’m calling Is a Citroen Xsara Braque even imaginable? half-sonnet, half-prose); most of things take shape as they go along, because of what’s happening in the world and in my life, in others’ lives at the time. In fact I’m afraid if I self-consciously try to write a poem to fit a certain book I’m going to fail miserably.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Oh, god. It’s all challenging. Maybe I’d say—challenge came when trying to see the book’s title. I like how titles can do so much. They can set a tone, suggest a scene, take care of a situation, jumpstart something, imply alternatives. The place they hold is a powerful place, isolated up there all by themselves.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

1955–1967: everywhere, all the time, second nature, main preoccupation, unconsciously; I especially liked a cedar-lined closet with a typewriter stored on its floor, and a spot on the Mississippi River I thought of as my place to be at home.

1967–1970: anywhere I could find to be alone, not as often as I wanted, awkward writer’s self-consciousness awakening, by hand in lined journals, on Royal tabletop gifted me by my father.

1970–1980: anywhere with time and privacy, by hand in lined journals, and on Royal, often in rented rooms I’d turn into a room of my own and for keeping nearby books of all kinds, with a big dictionary on a dictionary stand across the room so I’d have to walk over to it, changing my mind as I walked, finding other words than the one I stood up to go find.

1980–1990: in a room in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and then in a tiny place in Austin, Texas, then mainly in my room in my house in North Amherst, Massachusetts, usually between 8 AM and noon or 3 PM, when either my children or my work determined my hours, much handwriting in lined journals in between scheduled responsibilities.

1990–2014: often in my room at my husband James Tate’s house in Pelham, Massachusetts, anywhere from two to five or six days a week, typically from 2 PM on until what we wrote that day would be in shape enough for him to read mine to me and me to read his to him; with occasional interruptions for travel, switched to IBM Selectric then eventually to laptop, kept unabridged Merriam Webster across the room as usual, handwriting in journals especially on days when not in Pelham or on Royal desktop.

2015–2022: at any one of three tables and one desk in my house, I’d say about half of the day, most days, by hand in journal, on laptop, occasionally especially when not home, on phone usually in e-mails to myself.

As of March 7, 2022 I’m writing every morning for an hour or so on a long prose poem that I’ll hope to see to completion on March 7, 2023, and I’m writing the rest of any given day’s writing times on other books, poems, prose, in various stages of progress.

4. What are you reading right now?

Just as with writing I’m always reading more than one book at a time; this week those books include Herta Müller’s Father’s on the Phone With the Flies (2018) translated by Thomas Cooper, short aphoristic, surprising; Bianca Stone’s What Is Otherwise Infinite (2022), audacious, dauntless, the opposite of tame; Lewis Thomas’s Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (1983), this book’s first ten pages seem written for right now—one sentence: The final worst-case for all of us has now become the destruction, by ourselves, of our species.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Just this morning I was reading in Hyperallergic an article by Naz Cuguoglu called “The Art World’s Tainted Love for ‘Discovering’ Artists: The Case of Etel Adnan,” in which she rightly claims the art world, and by extension the literary world, claims to be righting wrongs of exclusion and underrepresentation while mostly ignoring reasons why recognition and wide appreciation occur in the first place. She quotes Adnan: “To be honest, I did not expect recognition. I was happy to keep going.”

Cuguoglu calls attention to and asks us to consider words such as discovery, finally getting their turn, forgotten, overlooked, and ignored. On a planet with a population of close to 8 billion, speaking over seven thousand languages, it has to be some kind of roll of the dice that determines who’s recognized and for what, when, and why, how, and what for. I hope everyone who writes begins by recognizing their own value and the value of the very act of their having chosen to write. I hope they pass their gift on to others who will in turn pass it on beyond themselves.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Are you with this question vesting in me the superpower I’ll need to see the one thing I’d change changed? I’ll pretend you are—poof!—value not determined by money or data.

The diverse and unruly lives of artists and many of those who support artists can’t be summed up. Hundreds, thousands of independent and independent-minded people spend resources of time and money publishing others and sometimes themselves. Thousands, tens of thousands and sometimes fewer than ten writers and readers benefit. A circle of friends, a culture in common, unity from coincidental habitation in space, authentic and not institutionalized gatherings, these naturally celebrate and benefit from their close associations. Some of us are natural-born loners, in life, while addressing, in spirit, an unseen, unknown universal audience of beloved strange familiars.

The trail from private to public is complicated beyond summary. I’ve always taken heart from the story of a Barcelona-based poetry prize that awarded third place a silver violet, second place a golden rose, first place a real rose.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina?

The suddenness of its title appearing, it seemed, out of nowhere. And thank goodness.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

When the title went on it.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Emily Pettit, my daughter, can claim that difficult role. I trust her every time. She has no problem questioning what always turns out to be questionable. I’m lucky to have her imaginative, principled, and quick understanding and her knowledge of all the ins and outs of poetry’s range. I trust her willingness to take on what has to be sometimes challenging, and I’m thankful for it.

I also trust strangers who are far away from my daily life, people I’ll never meet, never know.

And I trust a handful of friends I know it’s okay to send something new or in progress—not as often as I’d like, ha, for I don’t want to outstay my welcome. I’m not looking for advice so much as that scary electric sensation you get when you hit Send, or rarer still, drop something into a mailbox.

Knowing me, I’d like to send a lot of people a poem when I just finish it and am especially eager to have it seen by eyes other than mine, and taken in by another mind. But I resist it. I like the feeling of thinking of someone reading what I’ve sent, it tells me something. Picturing them reading what I’ve sent gives me insight into something I might want to do differently or feelings about something I’ve done being maybe okay.

And, of course, I trust every editor who’s ever published anything I’ve ever sent them!

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Ha, let me think............