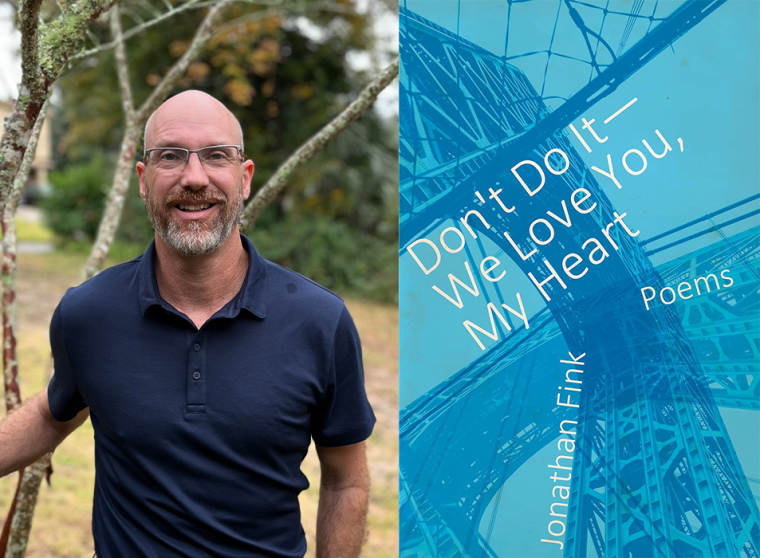

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jonathan Fink, whose poetry collection Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart, is out today from Dzanc Books. Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart features a range of poetic styles, including narrative poems, lyrical poems, and one-sentence poems that stretch across multiple pages. The title of the book comes from the famous story of a suicide prevented on the Hudson River’s George Washington Bridge; the jumper was stopped by a man who told him, “Don’t do it—we love you, my heart.” In this collection Fink traverses evolving national and personal landscapes, exploring subjects as diverse as growing up in West Texas at the end of the Cold War, the paintings of Goya and Leonardo da Vinci, and the language he shares with his baby daughter. Natasha Trethewey said that Fink “skillfully grapples with thematic material engaging larger social and political implications without sacrificing precision of language, clarity, and the quest for beauty that characterizes all of his work.” Jonathan Fink has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the state of Florida, and his writing has appeared in a wide range of publications from Poetry and the New York Times Magazine to the Journal of the American Medical Association and Slate. He currently lives in Pensacola with his wife and daughters and teaches at the University of West Florida.

Jonathan Fink, author of Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart.

1. How long did it take you to write Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart?

It’s always interesting to think about time as it relates to writing. Some of the earliest poems in the collection (just a couple) were written fifteen to twenty years ago and were not included in earlier collections. I revisited these poems and revised them a bit, and I hope that they fit in well with the arc of the collection. Most of the other poems were written over the past ten years or so, and the autobiographical poems follow my getting married to my wife, Julie, and having three daughters. More philosophically, the answer to, “How long did it take to write Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart?” would be that I believe poems rise to meet you when your experiences, perceptions, and empathy have evolved to a place to welcome the demands of the new work. So, in that case, it has taken the lifetime up to the point of each new poem to write it. I can’t imagine writing these poems prior to when they were written.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

One of the main challenges is always patience—not just the patience of submission and acceptances with literary journals, etc. but the patience to complete each poem. Many of these poems are longer, one-sentence poems, and it often takes me a long time in the writing process to discover the subject of the poem that evolves from the poem’s initial topic. I tend to add a little more to a poem each time I sit to write, responding to the poem’s expectations so far. Discovering the final arc of a poem’s progression can require a lot of patience.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I don’t really have a specific schedule. I tend to write when the combination of opportunity and interest converges. I tend to write best in the comforts and rhythms of home. Retreats and conferences and such are great spaces for renewal and inspiration, but they’re not great spaces for me [to do] actual writing. For example, many times I’ll write on my laptop while lying on the floor next to my daughters’ bunk beds after I’ve read to them and they’ve fallen asleep and my wife, Julie, has just fallen asleep as well. Chris Rock said that a house filled with sleeping children is quieter than an empty house, and that matches my experience as well.

4. What are you reading right now?

Mostly I’m reading through all the Harry Potter books again out loud with my daughters each night before bed. My daughters are eleven, eight, and five. I read through the series when my oldest daughter was younger and now the younger two are interested in the books, which I’ve enjoyed reading with them. Like all writing teachers, much of my reading is devoted to student work and books for classes. I’m also reading a lot of nature poetry in preparation for an institutional grant I received with my colleagues at the University of West Florida to establish a poetry and art nature trail in our university trail system. A great anthology I recommend is Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry (Mountaineers Books, 2023).

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Matthew Olzmann is a poet who has a deserved and devoted following. However, he is a writer deserving of a wider audience. His poems are rich with lyrical beauty, rhetorical depth, and piercing wisdom and insight. Two poems of his I would recommend are, “Letter Beginning With Two Lines by Czeslaw Milosz,” and “My Invisible Horse and the Speed of Human Decency.”

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

There is a wide range of styles to the poems in the collection (at least it seems that way to me), and, surprisingly, the wide range of styles and subjects made the organization relatively straightforward, organizing by time, subject, themes, and style. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a “strategy” for organization. I was just responding to how the poems seemed to fit together. I tried to judge the poems individually and then how they spoke to one another. Like my students, I am always a bit surprised to see my own psychological imprint on the page over many pages. Continuity and connection are inescapable if the poems are coming from the same attentive place.

7. What is one thing that your editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

In addition to, “Yes, we would like to publish the collection”? Michelle Dotter at Dzanc is a wonderful editor. Many editors these days are sometimes more like copyeditors or marketers, and Michelle is an editor in the classic mode of really investing in the language and structure of a collection. She is primarily an editor of fiction at Dzanc, and I love having a fiction editor edit my poems. She has a great fiction editor’s eye for the energy of a collection. Where does the energy start to falter? Where does attention start to wander? Her editorial suggestions do a great job of keeping a book’s energy up and its pacing fluid and focused.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart, what would you say?

The simplest and best of writing assurances: Trust your instincts and heart. Be welcoming and appreciative of the reader (who, of course, is also an extension of the self). Don’t worry about aesthetic categories or limitations. Have fun. Follow the trajectory of a piece wherever it might lead. Follow all poetic connections to be made in a poem, no matter how seemingly different.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart?

There are lots of ekphrastic poems in the collection, and I always appreciate my wife’s conversations with me (my wife is an artist and teacher) where we have a shared vocabulary across art and writing with terms like, “line,” “composition,” and “tone,” yet there are different implications across the art forms that can be enlightening too. Musical concepts regarding the variation of expectation and improvisation/surprise were also helpful, especially in relation to jazz and how a melody is established and then improvised upon. The listener holds both the established/expected melody and the improvisations in mind simultaneously, and pleasure is drawn from the awareness of both expectation and variation simultaneously. This concept can be applied narratively and poetically to hopefully satisfying effect for the reader.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Ezra Pound told Hemingway: “Write without evasion or cliché.” This is the most succinct and instructive writing advice I know. While the advice to write without cliché is fairly self-explanatory (though definitely not easy), I especially find myself returning to the evasion part of the instruction. What am I evading in my writing? Not just subject matter, but, more deeply, what am I evading emotionally? What does it mean to be truly honest in your writing? These are questions worthy of perpetual attention and vigilance for writers.