This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Roger Reeves, whose second poetry collection, Best Barbarian, is out today from W. W. Norton. In vivid, haunting poems written with lyrical precision and elegiac intensity, Best Barbarian traverses the literary and social landscape to probe stories of climate change, anti-Black racism, catastrophe, love, loss, joy, and rage, transcending time and space, speaking to and through the work of writers such as Walt Whitman, James Baldwin, Sappho, and Dante. “Borrowing and turning on its head the Western canon’s repeated warnings of civilization’s fall, Roger Reeves counters that the apocalypse ran contiguously with the inception and height of Western civilization because the white man’s rise was contingent upon the destruction of Black personhood,” writes Cathy Park Hong. “From that perspective, Reeves sees America as a necropolis to which he leads us―like Virgil―down into the underworld, where we meet the shades of Emmett Till, Oya, and Ezra Pound, among others.” Roger Reeves is the author of King Me (Copper Canyon Press, 2013) and the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, and a 2015 Whiting Award, among other honors. His work has appeared in Poetry, the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Austin, Texas.

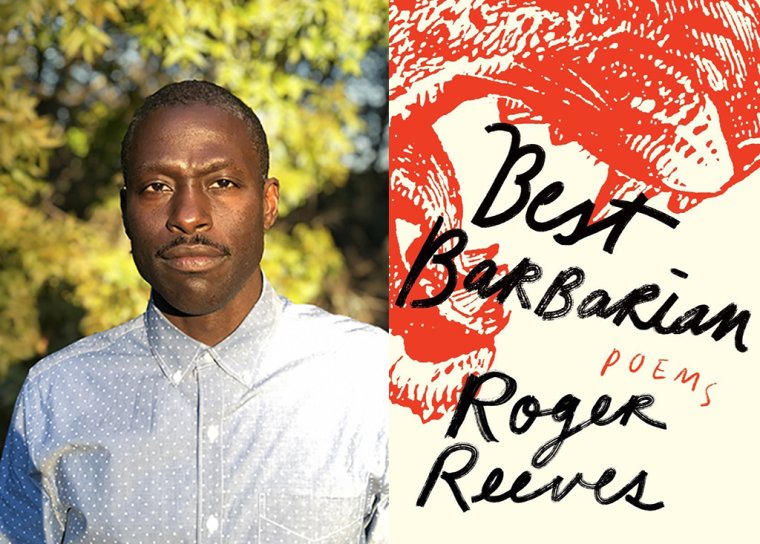

Roger Reeves, author of Best Barbarian. (Credit: Ana Schwartz)

1. How long did it take you to write Best Barbarian?

That’s an odd question because I had written another book of poetry, one I’m still working on, while writing some of the poems in Best Barbarian. If am going to speak solely chronologically, Best Barbarian took nine years because King Me, my first book of poems, came out nine years ago. So let’s go with nine years for simplicity.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most challenging thing about writing a book is thinking of “poems,” which are discrete art objects, as a book. I think of myself like a cabinet-maker. I like to make cabinets. I’m not an interior designer, which is what making a book is. When putting together a book, you must switch from making individual poems (which feel like books to me but that’s another discussion) to making something for which people will inhabit. In a book, the cabinets must fit in the kitchen. The vanity must slip into the bathroom and give you plenty of room to get to the shower. When making a book, you’re thinking about relations—how does this poem I wrote two years ago relate to a poem I wrote four years ago or two days ago?

Despite my reticence for becoming an interior designer, I enjoyed the process of putting Best Barbarian together. I structured the book more like a modal jazz tune with two very distinct solos, longer poems that were sections unto themselves—the middle of the book. The first and last sections announce the concerns, the melody and harmonics, of sorts. So when the book plays, it plays like one long song. You hear the original melody then you get these two solos, then you go back to the melody, but when you hear the melody again, it’s slightly different because the solos have changed your understanding of what the original melody was doing and could do.

What I also found difficult in writing Best Barbarian is what I find difficult in writing in general—giving up the poem, allowing it to go out into the world. I’m constantly tinkering, radically changing poems, asking it what else it has. I think this sort of process doesn’t always lend to making and publishing books quickly.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Where do I write: anywhere—at a desk, in an office, in bed, in the bathroom, on a run, in the shower, walking to the corner store, in an airplane. Though mostly, I write at a desk.

When do I write: in the mornings generally—first thing.

How often do I write: six days a week. I take off one day, sometimes two days, a week. I am often writing on several projects simultaneously, in several genres, so I do a bit of crop rotation. But if I’m honest, I’m writing everyday—changing a comma here, reworking a sentence.

4. What are you reading right now?

This morning I was reading Donald Revell’s White Campion and Dan Charnas’s Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm. Over the weekend, I had a hankering for some Elizabeth Bishop and reread Geography III (such a great book). I have also been reading Solmaz Sharif’s Customs and revisiting LOOK for an essay I’m revising. In terms of fiction, I have been rereading Morrison’s Beloved and Paradise. I’m excited to get into Gary Jackson’s book of poems Origin Story and Geoffrey Hill’s The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Lorenzo Thomas. He was poet, born in Panama, raised in New York City, and taught at the University of Houston, downtown campus. His work straddled many writing camps and collectives. A few days ago I was marveling at this wonderful poem titled “Diplomacy,” which appeared in the African American literary journal Callaloo in 1999. Thomas does such an amazing job of thinking inside a poem. The last stanza of “Diplomacy” reads: “Nothing is gained, perhaps / Except to understand / The eye-piercing cologne men wear / To transact filthy business.” More of that. I wish his work was discussed and lauded more. I wish we understood how many Black poets were writing truly transcendent, timeless poems, but we’ll never get to see them because they ran into the buzz-saw of American racism and lived in and through American apartheid.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

If I could change one thing about publishing, it would be that poets could make a living just writing poems. And do nothing else unless they chose to. And that we’d have a wider, more generous notion of excellence. And, that we—writers, editors, presses—had more funding opportunities to put on more audacious programming and collaborations.

7. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

I will miss writing “Something About John Coltrane.” I like the soloing that happens in that poem. It was the type of poem that felt amazing to be inside of it. I will miss reading the poems in proofs and realizing that indeed it is a book, and it’s a book that I always wanted to write, a book that surprised me in its vulnerability, in its reaching toward and addressing freedom.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

When my editor at W. W. Norton, Jill Bialosky, said I couldn’t make anymore changes. But seriously, I’m always working on the manuscript up until the last moment. I want to make sure I’ve gotten the poems some place that I couldn’t see when I started them. I want the poems to journey somewhere emotionally, meditatively. I always think of the adage from Robert Frost—“no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader; no tears for the writer, no tears for the reader.” This adage has guided and continues to guide me

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I have several trusted readers. Solmaz Sharif, Chris Loperena, and Monica Jimenez. They are my trusted readers and listeners because they have big ears; they can hear diverse and wildly different sorts of music. They also want more for the world, for the poem in the way that I want more.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Write. Get out of the way of the writing. Don’t make it precious. Sit down and get to it.