This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Terra Trevor, whose memoir We Who Walk the Seven Ways is out now from the University of Nebraska Press. In this personal history, Trevor considers what it has meant to navigate the world as a “mixed-blood” Native woman, whose light complexion belies her ancestors among the Cherokee, Lenape, and Seneca peoples. Born to a white mother and American Indian father in the early 1950s, Trevor delves into her relationship with her paternal grandparents and Auntie, who taught her about the heritage that felt more authentic than her white identity, as well as the elder Native women who welcomed her into their community and schooled her in the “seven ways” of being in tune with Native tradition. Moving back and forth across time, Trevor recounts the complexity of her relationships and experiences and how they were shaped by U.S. law and policies governing Native life and culture. Foreword Reviews calls We Who Walk the Seven Ways “a moving memoir about friendship and identity.” Terra Trevor is an essayist whose work has been included in more than a dozen books, including Tending the Fire: Native Voices and Portraits (University of New Mexico Press, 2017). She is the author of the memoir Pushing Up the Sky: A Mother’s Story (Korean American Adoptee Adoptive Family Network, 2006).

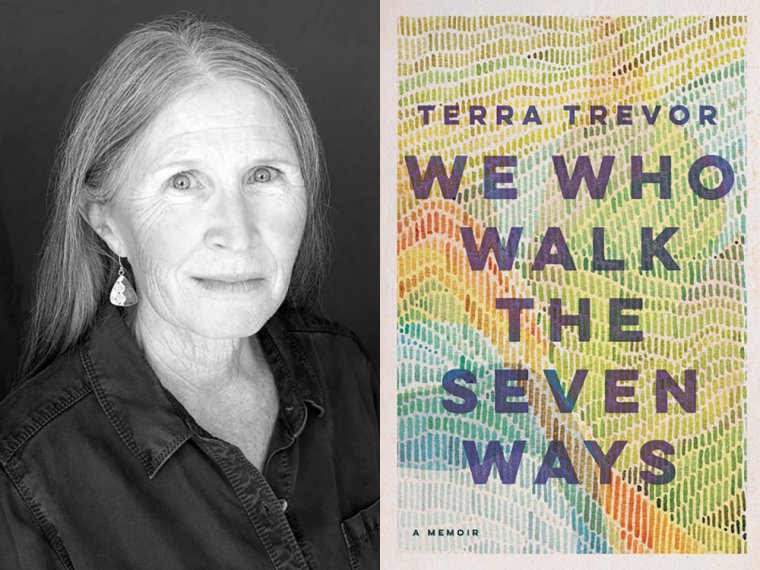

Terra Trevor, author of We Who Walk the Seven Ways. (Credit: Chris Felver)

1. How long did it take you to write We Who Walk the Seven Ways?

About nine years. In 2013 I was invited to contribute a chapter to Unraveling the Spreading Cloth of Time: Indigenous Thoughts Concerning the Universe. While working with the editor of this anthology, it soon became clear to both of us that I had a much bigger story to tell. After the book was published, I began working on the manuscript that would become We Who Walk the Seven Ways. I could feel the story emerging within me, but the writing wouldn’t come; so I worked on it off and on while working on other writing projects. Then in 2017 my story began to pour forth and flow like a fast river. This is when I began to understand that I could not write the book earlier because I hadn’t finished living the story. In 2021, I completed a solid first draft and began working with my editor on revisions.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

This book is not only about me. It’s also about the people whose lives are braided with mine, defining it and shaping me. These women—the ones with the grandmother faces, walking the seven ways—how they made me laugh and told me the truth even when it was hard for me to listen. While writing, I brought them all back, made them come alive again—the women who, for over three decades, lifted me from grief, instructed me in living, and showed me how to age from youth into beauty. I felt a great debt of responsibility to tell the story we share with integrity, honoring their lives.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’ve been writing for more than four decades. When I was a young mother-writer I learned to write within the nooks and crannies of my life. Back in those days, I had my desk with a typewriter—in later years a computer—tucked into a corner near the kitchen and laundry room. Now my babies are all grown. I no longer sneak off to finish that one last page. I have the freedom to work on my laptop and move about. Yet I still find weaving writing into my everyday life most productive, especially for rough-draft writing. Often I explore writing topics in my journal. First, with pen and paper, I write three pages of raw, rough-draft thoughts. The purpose is to tap into my mind and see what might be lurking in my subconscious. Later I pick through my scribbles and discover a gem. Sometimes a single sentence in my journal leads to a full chapter or essay. But when I’m working to complete a project, I write and revise constantly until I’m happy with it. Then I will go a day or two without looking at the work so I can return to the piece and edit with fresh eyes and a clear mind.

4. What are you reading right now?

I read all the time. I cannot remember when I couldn’t read. Nor can my mother. Listen to her, and you’ll hear about a child in diapers with a book on her knee. Right now, I’m reading Unpapered: Writers Consider Native American Identity and Cultural Belonging. I’m a contributor to this book, and when my copy arrived I could not put the book down. Unpapered is a collection of personal narratives by Indigenous writers exploring the meaning and limits of Native American identity beyond its legal margins. Reading this book feels like I’m holding my family and my Native community in my arms. Native heritage is neither simple nor always clearly documented, and citizenship is a legal and political matter of sovereign nations determined by such criteria as blood quantum, tribal rolls, or community involvement. Given that tribal enrollment was part of a string of government programs and agreements calculated to quantify and dismiss Native populations who do not hold tribal citizenship, the book charts how current exclusionary tactics began as a response to non-Indigenous people assuming a Native identity for job benefits and for other personal gains. It has expanded to an intense patrolling of identity that divides Native communities and has resulted in attacks on peoples’ professional, spiritual, emotional, and physical states. Each contributor brings incredible urgency and healing to a most necessary conversation.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Sandra Cisneros, Gloria Anzaldúa, Toni Cade Bambara, Annie Dillard, and Joy Harjo influenced my early writing years. I read a wide variety of Native authors, and the works of contemporary and classic Native writers. My writer voice is shaped by books with a collective of Native voices, with each writer telling a single story, working together to bring forth a whole book.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of We Who Walk the Seven Ways?

Throughout the entire process of writing this book I began to shed layers and feel connected to myself in wholly new ways, comfortable in my skin while being seen—more of everything, and less concerned with what other people might expect of me. How the boundary of time collapsed around me. Long ago memories, almost forgotten, began to spill out and stuck to me like lint on a black dress. Feelings I’d blocked out began to surface—feelings that had remained untouched in my heart, in that place of perpetual remembering. Sounds and scents returned, and writing magic happened when I let go of expectations, trusted my characters, and let them take me to unexpected places the story was destined to go.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Banjo music and storytelling. After dinner the kitchen was alive with music. My grandpa played the banjo, the uncles played the fiddle and guitar, and grandma played the harmonica. She took out her teeth and dropped them into her apron pocket before she started playing. I grew up with what is now known as the mixed-blood fiddle tradition. It reflects that we are a mixed people of Native and other heritages, and the music defines who mixed-bloods are, a blend of Native and European descents.

Before bed, Grandpa and Auntie rounded up all the kids and told us what we called Indian stories. Auntie always told us creation stories—the teaching stories, the traditional ones. But Grandpa told us hair-raising, real-life stories about things that had happened to him as a young boy, as a man, and while raising seven children with Grandma. The remembering often sent Grandma outside to sit on the back porch. When the storytelling ended, I went out back and sat on the porch with Grandma. We smelled the rain or watched the stars—one by one, as they began to light the sky—and let the chill air of mother earth embrace us.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started We Who Walk the Seven Ways, what would you say?

Listen deeper. Dream bigger. Hold tight to faith and cultivate a wide variety of dreams. Be open to the unexpected, and understand that the dreams meant for me will happen.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Long walks while the story formed within me, and while writing, was my practice, meditation, and prayer, along with open spaces of stillness and solitude. I also did much research to make sure my own memories and the stories told to me matched the actual history taking place within the United States. All of this was followed by many rewrites and revisions until my story felt as comfortable as my own skin. Then I rewrote and revised more and took my story right to the edge of causing me to feel a bit uncomfortable in order to make sure I was genuine.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

The funniest advice I’ve received came from a friend who penned a successful column in a hunting and fishing magazine. He said to never let the facts get in the way of a good story. He was referring to his fishing tales of landing the big one. Though his daughter unintentionally misquoted her father and said, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” We are still laughing.

But kidding aside, the best advice I’ve received came from Eudora Welty. She was talking to Natalie Goldberg and said, “It’s good they want to publish your book. But try not to think about it too much.”