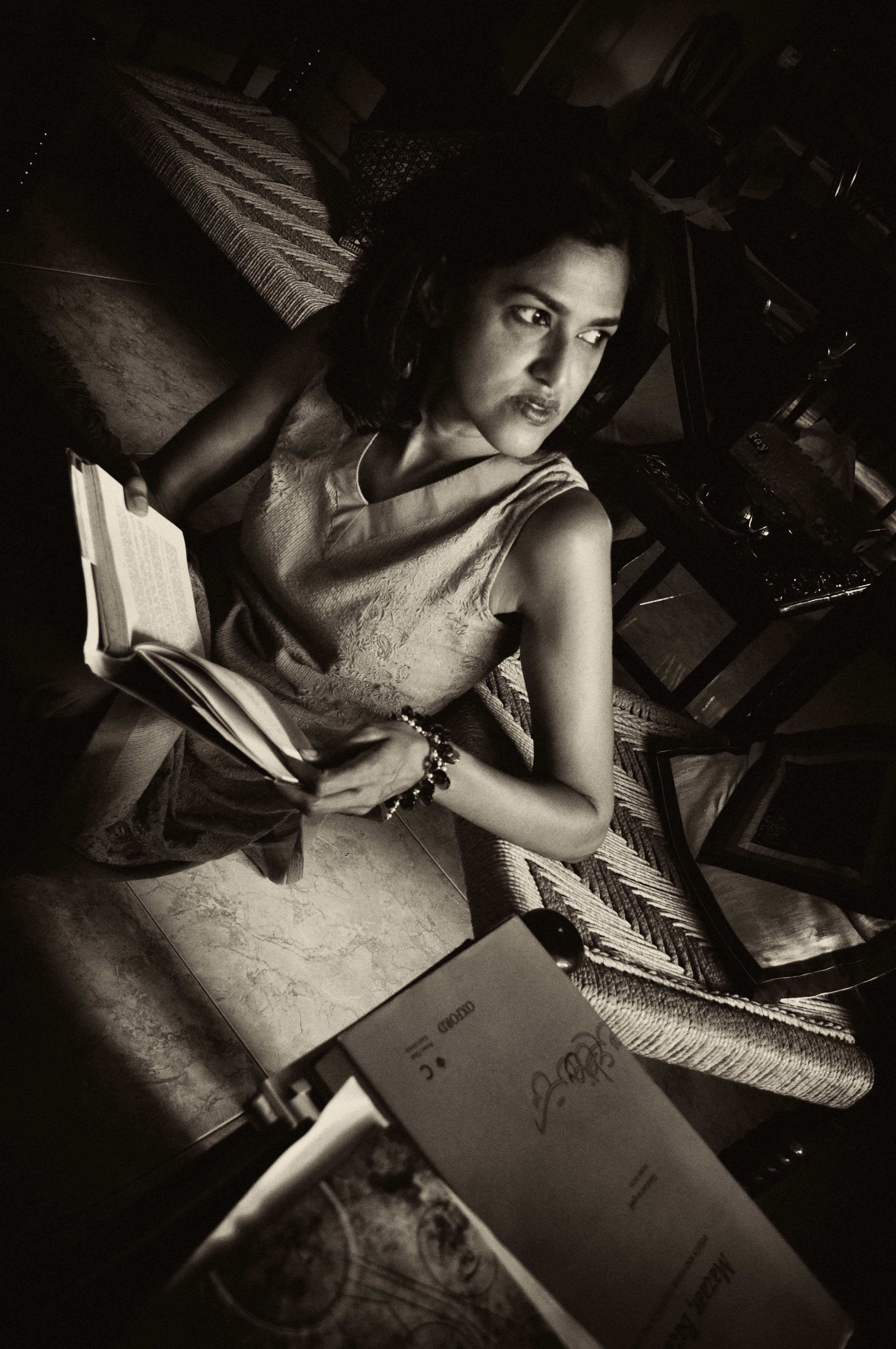

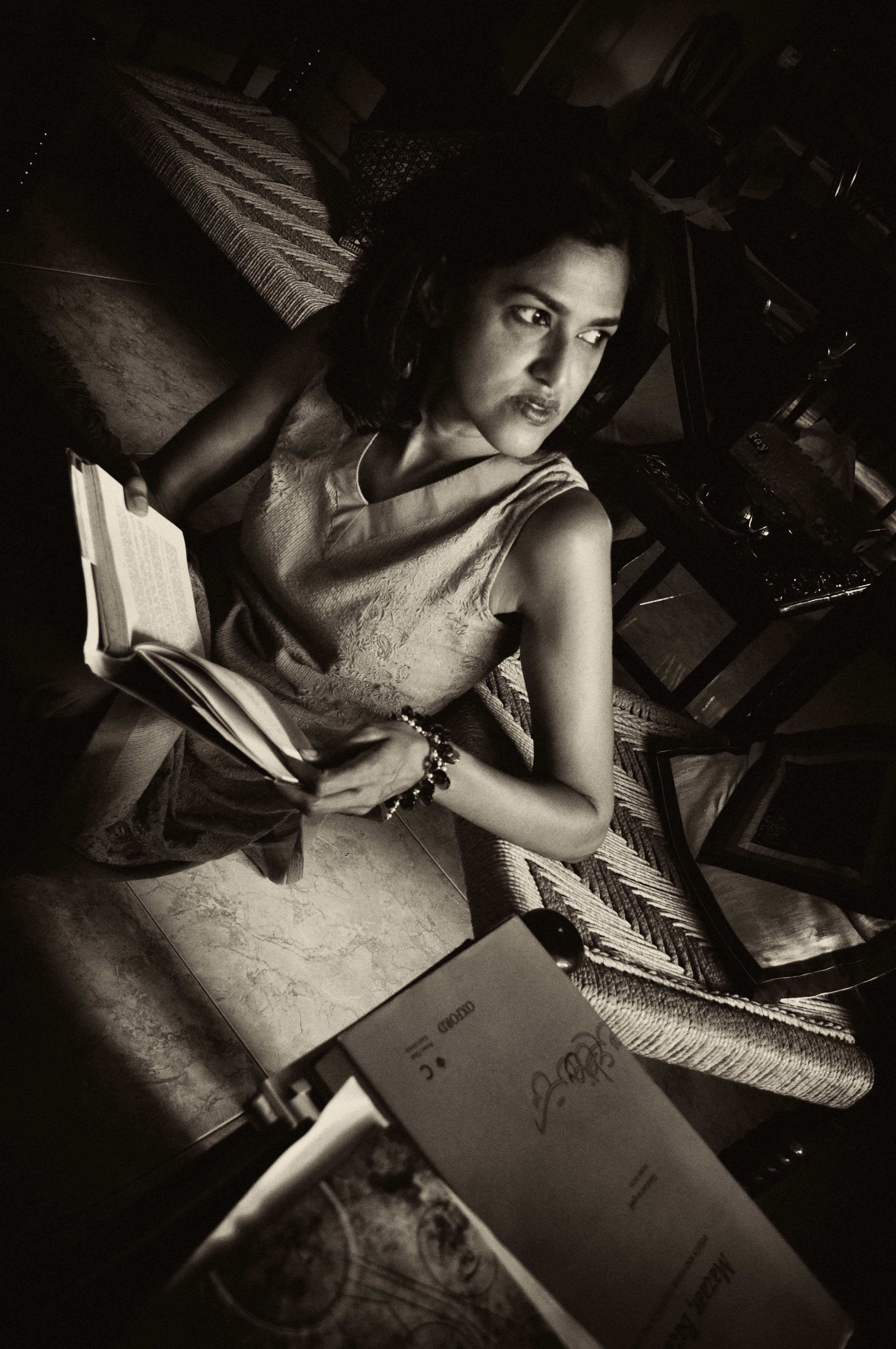

October writer-in-residence Sehba Sarwar blogs about P&W-supported Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB), an alternative arts organization. A writer and multidisciplinary artist, Sarwar uses her poetry, prose, and video/art installations to explore displacement and women’s issues on a domestic and global level. Her first novel, Black Wings, was published in 2004, and she is currently working on a second manuscript tentatively entitled "Island."

This month, as Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB) launches our thirteenth season, I’m reminiscing about Fall 1999, when my friend Marcela Descalzi asked if I wanted to do anything before the start of the next millennium. At that time, Houston offered few options for new writers, performance artists, and grassroots activists.

This month, as Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB) launches our thirteenth season, I’m reminiscing about Fall 1999, when my friend Marcela Descalzi asked if I wanted to do anything before the start of the next millennium. At that time, Houston offered few options for new writers, performance artists, and grassroots activists.

“I want to create a space for artists to share work about issues that matter to us,” I said. “I also want to perform a poem about political events unfolding in Pakistan, my home.”

We formed a collective, inviting three other women writers and artists—Christine Choi, Donna Perkins, and Jacsun Shah—to join us. Dedicating hours in coffee shops, we finally agreed on Voices Breaking Boundaries as our group’s name. Our logo was the globe viewed from the southern Hemisphere. We wanted to offer a new lens through which to experience the world and to create space for artists and audience members from different backgrounds to gather, share art, and learn from one another.

Without thinking of the outcome, I submitted a grant application to the Houston Arts Alliance and was awarded $4,500. We decided to use the funds to print postcards and pay honoraria to artists. Each of us was teaching at that time, so we didn’t pay ourselves even though we performed at the shows. During our first year, we created monthly lineups in a local bookstore, featuring performance poets, academics, high school students, capoeira dancers, and drummers. In February 2001, after our collaboration with the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and Himal South Asia (Nepal) to offer a South Asian film festival, we knew we had to respond to our audience and incorporate VBB into a nonprofit arts organization.

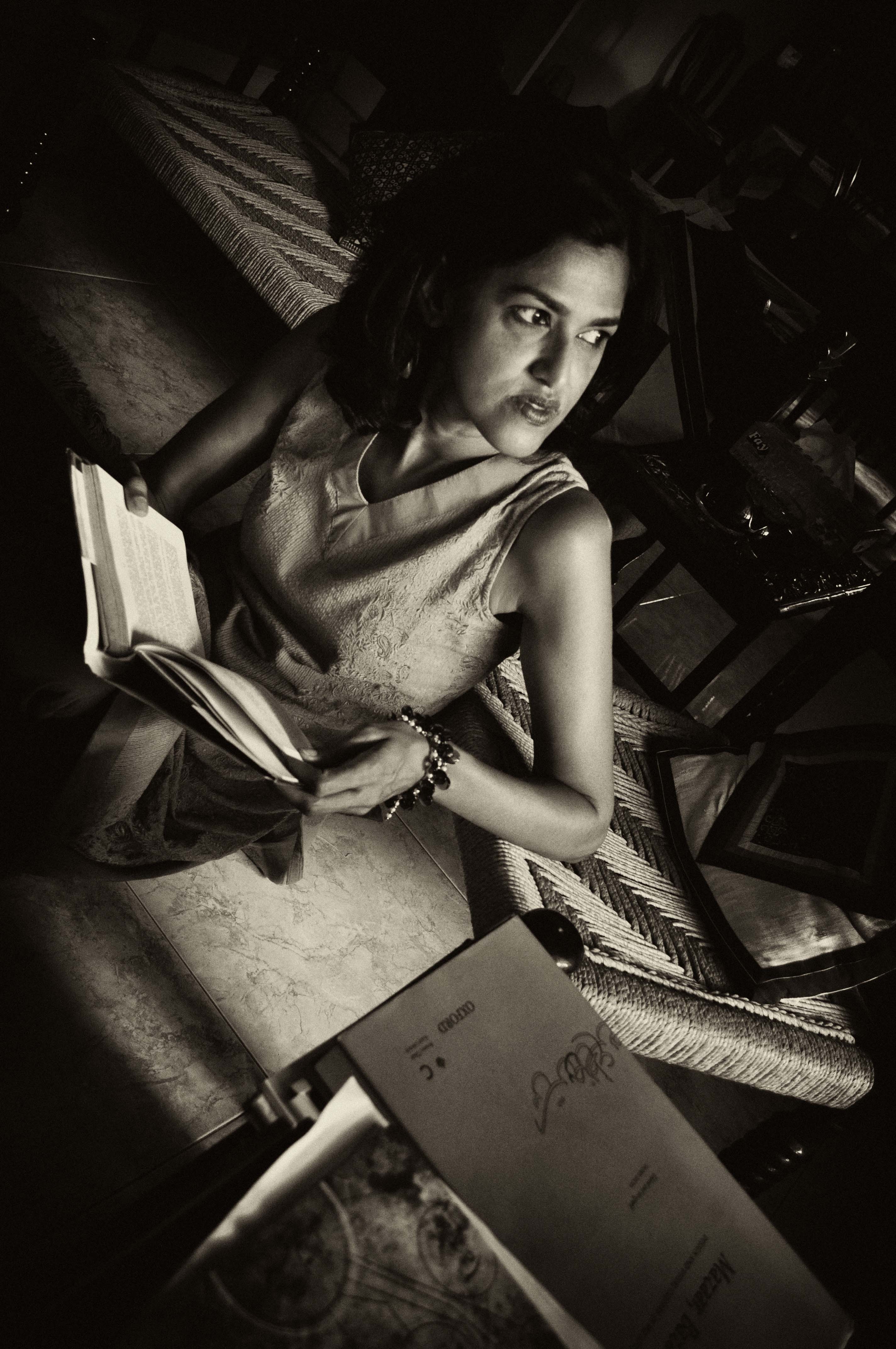

Fast forward to Fall 2012. I’m still writing and now draw a salary as VBB’s salaried artistic director. Over the years, VBB has received free performance and exhibition space and has collaborated with many other organizations, including Arté Publico Press, Project Row Houses, DiverseWorks, and Inprint, Inc., and has featured artists such as Arundhati Roy, Bapsi Sidhwa, and Patti Smith—all while continuing to tackle some of the most controversial issues of our times. We have carved a niche for our unique productions, living room art, through which we convert residential homes into art spaces and use the experience to create connections between Karachi, my home city, and Houston, where I’ve lived for some time. The productions, elaborate one night flares, meld spoken word, music, performance and videos with installations.

Fast forward to Fall 2012. I’m still writing and now draw a salary as VBB’s salaried artistic director. Over the years, VBB has received free performance and exhibition space and has collaborated with many other organizations, including Arté Publico Press, Project Row Houses, DiverseWorks, and Inprint, Inc., and has featured artists such as Arundhati Roy, Bapsi Sidhwa, and Patti Smith—all while continuing to tackle some of the most controversial issues of our times. We have carved a niche for our unique productions, living room art, through which we convert residential homes into art spaces and use the experience to create connections between Karachi, my home city, and Houston, where I’ve lived for some time. The productions, elaborate one night flares, meld spoken word, music, performance and videos with installations.

And around us, more communities of color and artist initiatives have sprung up. Any given weekend, one can cull from an array of choices to experience art. The city is “minority-majority,” serving as a prediction of demographic shifts across the United States. There’s still much work to be done and sometimes I feel challenged by how often we circle back to the same issues: immigrant rights, women’s reproductive rights, education awareness, racial stereotyping, and the United States' role in global conflicts. But at the same time, I’m grateful for the support VBB continues to receive from arts organizations like Poets & Writers. Looking back at 1999, I couldn’t have predicted where our collective would land. I do know, however, that in the wide expanse of Houston, the United States, and the world, there’s room for many more artist initiatives—and that our story speaks to the urgent need for more alternative voices to converge.

Photos: (Top) Sehba Sarwar. Credit: Emaan Reza. (Bottom) Fall 2011 living room art production Third Worlds: Third Ward/Karachi. Credit: Eric Hester.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Houston is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives.

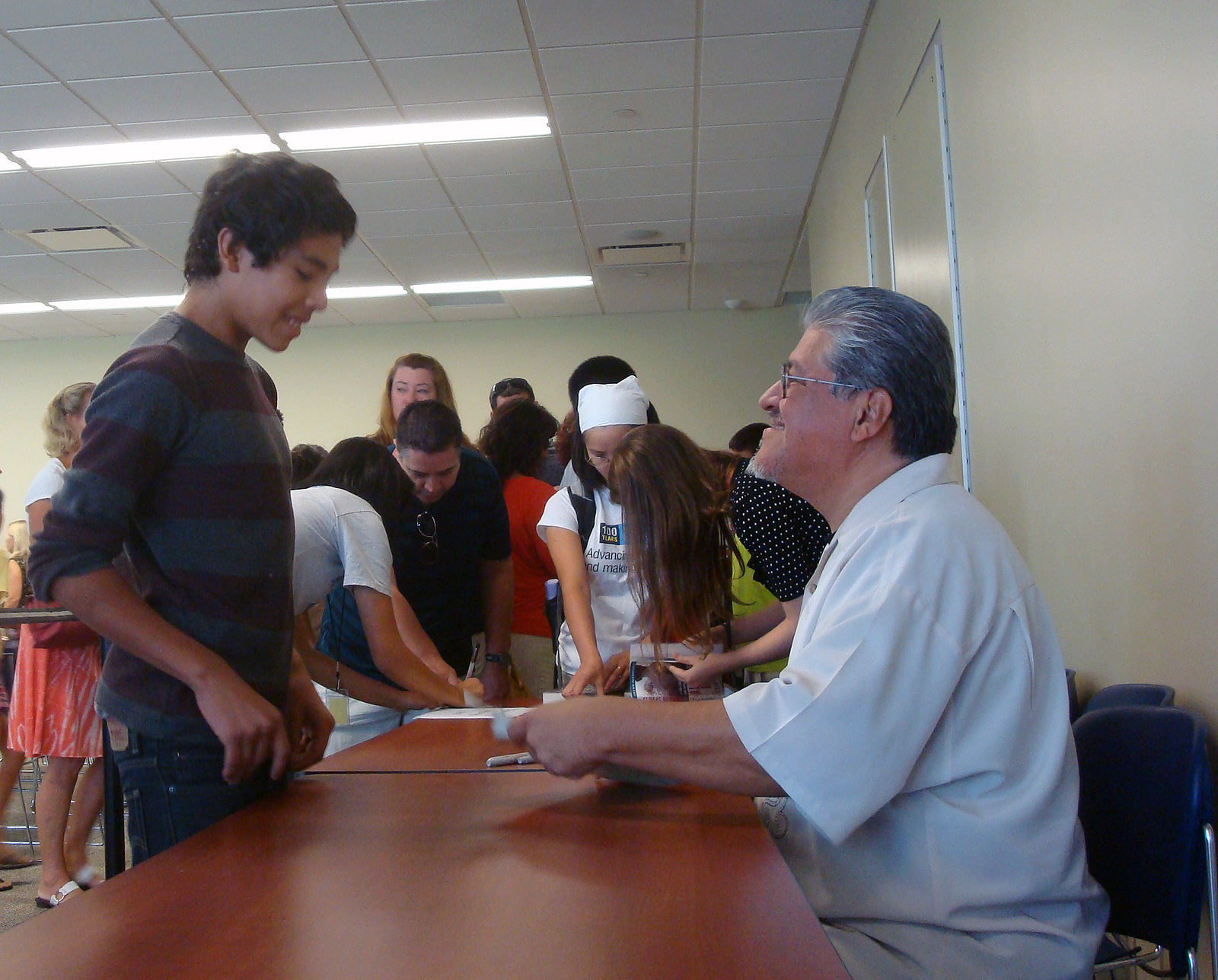

In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives. As Sunday afternoon temperatures climbed toward triple digits, a large crowd gathered in the comfortable confines of the Fullerton Public Library’s new Community Room. Families, teachers, and high school and college students waited for the arrival of Luis Rodriguez, author of Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A. and director of

As Sunday afternoon temperatures climbed toward triple digits, a large crowd gathered in the comfortable confines of the Fullerton Public Library’s new Community Room. Families, teachers, and high school and college students waited for the arrival of Luis Rodriguez, author of Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A. and director of

This month, as Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB) launches our thirteenth season, I’m reminiscing about Fall 1999, when my friend Marcela Descalzi asked if I wanted to do anything before the start of the next millennium. At that time, Houston offered few options for new writers, performance artists, and grassroots activists.

This month, as Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB) launches our thirteenth season, I’m reminiscing about Fall 1999, when my friend Marcela Descalzi asked if I wanted to do anything before the start of the next millennium. At that time, Houston offered few options for new writers, performance artists, and grassroots activists. Fast forward to Fall 2012. I’m still writing and now draw a salary as VBB’s salaried artistic director. Over the years, VBB has received free performance and exhibition space and has collaborated with many other organizations, including Arté Publico Press, Project Row Houses, DiverseWorks, and Inprint, Inc., and has featured artists such as Arundhati Roy, Bapsi Sidhwa, and Patti Smith—all while continuing to tackle some of the most controversial issues of our times. We have carved a niche for our unique productions, living room art, through which we convert residential homes into art spaces and use the experience to create connections between Karachi, my home city, and Houston, where I’ve lived for some time. The productions, elaborate one night flares, meld spoken word, music, performance and videos with installations.

Fast forward to Fall 2012. I’m still writing and now draw a salary as VBB’s salaried artistic director. Over the years, VBB has received free performance and exhibition space and has collaborated with many other organizations, including Arté Publico Press, Project Row Houses, DiverseWorks, and Inprint, Inc., and has featured artists such as Arundhati Roy, Bapsi Sidhwa, and Patti Smith—all while continuing to tackle some of the most controversial issues of our times. We have carved a niche for our unique productions, living room art, through which we convert residential homes into art spaces and use the experience to create connections between Karachi, my home city, and Houston, where I’ve lived for some time. The productions, elaborate one night flares, meld spoken word, music, performance and videos with installations.