This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Christine Kandic Torres, whose debut novel, The Girls in Queens, is out today from HarperVia. Set alternately in 1996 and early-2000s New York, the novel follows Brisma as she seeks to make sense of sexual-assault allegations against her high-school boyfriend, Brian, now a St. John’s University baseball player. On the cusp of college graduation when she learns about the accusations against him, Brisma seeks out Brian’s accuser and looks back on her own confusing memories of her romance with him. Brisma must also reckon with her friendship with Kelly, who defends Brian despite Brisma’s growing misgivings. While Brisma and Kelly supported each other growing up in the hardscrabble neighborhood of Woodside, Queens, Brisma must confront the ways in which sexism, racism, and classism have long pitted them against each other. Publishers Weekly calls The Girls in Queens “incisive and keenly observed.... Torres hits every note perfectly.” Torres has received support from Hedgebrook, Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA), the Jerome Foundation, and the Queens Council on the Arts. Her fiction has been featured in publications such as Catapult, Kweli, and Lunch Ticket.

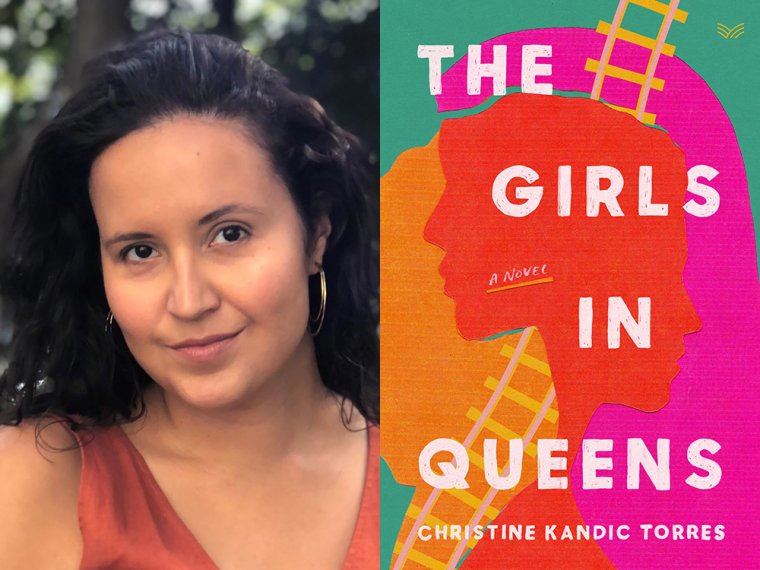

Christine Kandic Torres, author of The Girls in Queens.

1. How long did it take you to write The Girls in Queens?

It took me five years, more or less. The idea first came to me when the Mets made it to the 2015 World Series. I was lucky enough to win tickets to a game at Citi Field, and being in the new stadium made me nostalgic for the last time the Mets (or “Los Mets,” as Latinx fans often call the team) made it deep into the playoffs at Shea Stadium in 2006, but ultimately lost. I wanted to bring that time to life in a story, to capture what it meant for working-class kids of color to be represented by their hometown team and for that team to actually play well—historically something of an anomaly for the Mets.

At the same time, the horrific Brock Turner sexual-assault case was beginning to get attention in the news, and my fascination with women who defend and support violent men came into focus. I had been writing short stories until that point, but I realized I actually had a novel-length story to tell, one that would marry my baseball nostalgia to my exploration of how and why some women—including survivors of sexual assault—end up protecting abusers.

The idea scared me a little, of course, and so I didn’t start writing the novel in earnest until 2017, then went through several drafts until I signed with my agent in 2020.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I knew early on that the novel would be told in the alternating timelines of 1996 and the early 2000s. But I wasn’t sure exactly how the timelines would fit into place. Figuring out the structure of the novel was a challenge. But once I created an outline on index cards of the broad strokes of each chapter, I was able to visualize the timelines and more clearly see how they connected. I also realized that the alternating timelines would serve the purpose of mirroring a trauma victim’s memory. The first half of the book reads as the narrative that Brisma, the protagonist, has told herself in order to survive; the second half exposes the seedier aspects of her experience that she’s mentally edited out. Unlocking that felt like solving a puzzle.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’ve come to accept that I write in stolen blocks of time, and definitely not every day. I will block off long weekends when my husband can shoulder the lion’s share of childcare. If I’m heavy into revision on a project and on deadline, I will even take a few days at an Airbnb or a friend’s place where I can work undisturbed and crank out some pages.

Becoming a mom has also helped me to be as efficient as possible with the time I carve out for myself. When my infant son would sleep for long naps, I’d sometimes strap him into a baby carrier on my chest, rocking from side to side, and type on my laptop, which I’d stacked elbow-high on Buy Buy Baby boxes. Though that was hardly a regular routine: I’d do it when the brain fog and post-partum anxiety didn’t feel insurmountable that day.

4. What are you reading right now?

I usually have several books going across different mediums. I’m reading Victoria Buitron’s memoir, A Body Across Two Hemispheres, and Cleyvis Natera’s novel, Neruda on the Park, and I’m listening to Dave Grohl’s The Storyteller (I can’t help it, I love a celebrity memoir).

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Girls in Queens?

In the first draft of the manuscript, the girls were almost irredeemably mean to each other. I wanted to write female friendship in a way that felt honest to me, showing how the female characters strain against the patriarchal influences of competition and machismo but are buoyed by love and pride in each other’s survival. I was hitting the tough notes too hard. During subsequent revisions, I wrote on a piece of paper “SMALL KINDNESSES IN FRIENDSHIP” and taped it on my wall to remind myself to write toward this compassion. Making concerted efforts to fold this gentle strength and kindness into their interactions helped them become more well-rounded characters and helped ground their joy and fierce loyalty to each other in a deep, complicated love. These efforts also helped to soften me as a person a bit—a softening that was aided, I am sure, by my becoming a parent during this time.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Trying to simultaneously be a functioning parent/full-time caregiver in this world.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book stuck with you?

My editorial team was consistently supportive in maintaining my voice through revisions and copy edits of the novel. I felt like team members went out of their way to make sure I felt empowered to publish the story as I envisioned it, with all of its New York City nuance and language. I think it helped tremendously to have people on my team who understood, on some level, the world I was writing about. Despite some advances over the last few years, the demographics of the publishing industry remain wildly unbalanced, and my positive experience served to underscore for me personally how important and beneficial diverse representation can be for all.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Girls in Queens, what would you say?

Wow. I know she had the hustle in her to finish a manuscript and shop it around to agents and editors, so I don’t think she would have needed to hear encouragement about that. What I would tell her, though, is that her voice deserves to be heard.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Girls in Queens?

I had to research and rewatch old Mets games to get details correct for the games that appear in the novel. I actually misremembered the game in which Endy Chávez made his incredible catch in the National League Championship Series against the Cardinals. It was such a wonderfully miraculous moment that I thought it must have happened earlier in the series, in a game the Mets won; sadly, it hadn’t. I also reread books about the Mets like Pedro, Carlos, and Omar: The Story of a Season in the Big Apple and the Pursuit of Baseball's Top Latino Stars by Adam Rubin and Jeff Pearlman’s The Bad Guys Won! A Season of Brawling, Boozing, Bimbo Chasing, and Championship Baseball With Straw, Doc, Mookie, Nails, the Kid, and the Rest of the 1986 Mets, the Rowdiest Team Ever to Put on a New York Uniform—and Maybe the Best.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I attended a seminar taught by Victor LaValle about how to recognize and implement action in fiction, inspired by the kind of storyboards artists and writers use when creating a comic book. Mapping out the literal actions characters took in each scene helped him to see if they were moving the plot along or just sitting around yapping. I kept this in mind, especially as I revised The Girls in Queens—so much of which deals with the interiority of its characters—and I think it helped to tighten the pace and keep the plot moving forward.