Victoria Chang and I met nearly twenty years ago at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She struck me as being fiercely inquisitive and determined to soak up every bit of the conference experience. In our workshop with poet Michael Collier, I recall reading early drafts of poems in which she was exploring many different modes: persona poems, pastorals, and a sequence of ekphrastic pieces exploring the figures and shadows of Edward Hopper’s paintings. Approximately a year later, in 2005, her first poetry collection, Circle—which uses the concentricity of the shape to address themes of womanhood, family, and history—was published with Southern Illinois University Press. Since then Chang has written six more volumes of poetry, including OBIT (Copper Canyon Press, 2020), which received a Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in poetry, and the PEN/Voelcker Award. A collection of essays, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief (Milkweed Editions, 2021), soon followed and included multimedia work in which family photographs and letters, official documents, and other ephemera played with and off of epistolary text. Chang has also edited an anthology of contemporary Asian American poetry and published a picture book for children as well as a middle grade novel in verse. In the past two decades her writing has been recognized with many other awards: a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Fellowship, the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award, a Lannan Residency Fellowship, and the Chowdhury Prize in Literature. Chang currently serves as the Margaret T. and Henry C. Bourne Jr. Chair in Poetry and as the director of the Poetry @ Tech Program at Georgia Tech.

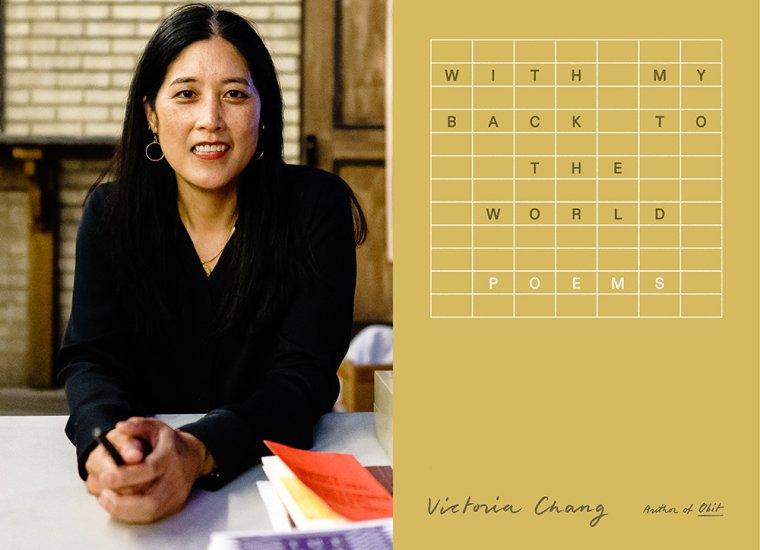

Victoria Chang, author of With My Back to the World (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024). (Credit: Pat Cray)

While revisiting Chang’s books, especially her poetry collections, I was delightfully immersed for long stretches of time. Like an actor who fully commits to her choices in a dramatic scene, Chang thrives at embodying and vocalizing universal feelings of anxiety, joy, grief, fear, and wonder. Further, it’s as if readers of her poetry are invited to visit a theater designed to accommodate a form or tradition with which she is obsessed, like the elegy, the letter, the prose poem. Reading her work chronologically, I was struck by how the personae adopted in Chang’s earlier books peel away gradually, such that the feelings animating her new poems are closer to the surface and more discernible to the reader.

Chang’s latest collection, With My Back to the World, available April 2 from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is fully engaged with Agnes Martin’s paintings, drawings, and writings. Martin, whose artistic output peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, is best known for her minimalist canvases composed of faint-lined grids in monochromatic tones. For a period of time Martin’s interests drifted away from canvases and towards notebooks in which she would draw, philosophize, and write poems. For Chang, who characterizes herself in her new book as a mid-career artist wrestling with artistic and spiritual crises, Martin serves as an example and a creative muse. Chang’s poems even borrow the titles of Martin’s paintings while also imitating Martin’s artistic forms and gestures as a way of expressing her own grief and sorrow. In one salient moment from a poem titled “Play, 1966,” Chang writes, “Once I write the word depression, it is no longer my feeling. It is now on view for others to walk toward, lean in, and peer at.” In With My Back to the World, Chang expertly probes the limitations of art’s ability to offer comfort or satisfaction.

This conversation began on a brisk fall afternoon in a Berkeley café where Chang and I warmed our hands with steaming cups of tea and continued over e-mail into the winter.

I began preparing for this discussion by rereading your debut poetry collection, Circle, immediately after studying your seventh and newest book of poems, With My Back to the World. What surprised me was how many of your current themes trace all the way back to your first published poems. I detected many throughlines: portraits of women searching for their own identity, often in contexts dominated by men; a preoccupation with the visual arts; anxiety over your place in the world as you straddle two cultures, Chinese and American. Formally, however, your work has become far more adventurous in the last two decades. Can you talk about those two qualities, consistency and change, as they relate to the writer and artist’s life?

When I first started writing poems, I thought I was supposed to sound like everyone else. It took me several years and several books to realize that mimicking others was a form of self-erasure, and I’m sure my mimicking annoyed the people I was mimicking or perhaps over-conversing with. I am a person who lacks confidence in my own selfhood. I am slow to ask myself those hard questions regarding what I want to write and how I want to write. I am also very organic—I live organically, very unplanned. I am a wanderer and a wonderer. I am more interested in process than I am in outcome, increasingly so. More and more I view artmaking as a way of being, perceiving, and living.

On consistency and change, I think it’s important to be true to who we are, but also to be very open to change, allowing the writing to tell us where to go. I also think that being an artist is about being fearless. Change can be scary. I am most interested and excited to make art when I feel like I am changing and growing. Yet that is also when I am most uncomfortable, especially when my hunch is that whatever I’m doing might not be interesting to anyone else but me.

Can you elaborate on that discomfort? It seems like a necessary quality for an artist to produce great work.

For me, a lot of artistic comfort—and perhaps life discomfort—centers around shame. If I feel a particular shame, a desire to hide, I try to approach that feeling through writing or visual art. I don’t think I do this to expose myself, but I try to build some kind of imaginary relationship with that shame to interrogate it and ask questions of it through art. With my book OBIT, that shame centered on exposing my deep and long-term sadness and grief about my parents and their illnesses. No one wants to hear about how sad you are, or what kinds of caretaking problems you are having, especially if those problems are decades long. At some point I stopped talking to anyone about it. But then it all flooded out, so I decided to forget all that shame and talk to a proxy self that might have wanted to hear some of the things I was feeling. I’ve said this many times before, but the difficulty with [one’s] grief and sadness is that those feelings are often asynchronous with other people. I had a voice in my head: “Let me tell you what I have felt, am feeling, let me see if it is possible to describe this grief to you…”

It’s fascinating to hear you say that you’re more interested in process than outcome. Your books often exhibit your obsession with a style or form, as if you’ve discovered a new vein of ore and then exhaustingly mined it for every bit of creative gold that you can. OBIT explores and stretches the form of the obituary. The Boss (McSweeney’s, 2013) is written in breathless quatrains. Poems from The Trees Witness Everything (Copper Canyon Press, 2022) riff off lines by W. S. Merwin. In With My Back to the World, you immerse yourself in the life and art of Agnes Martin. Your books are always richly layered and arrayed. What creative challenges do you face when you transition from writing poems to completing a book?

Leave it to a poet to so naturally think of a metaphor such as “a new vein of ore.” I’ve heard people tell me that my work seems “neat” or “organized,” or even “preplanned.” I understand the impulse to think this. But I think of the book or outcome as simply a representation of the process of thinking and feeling, and as you say, obsession, step-by-step. In no way am I planning anything ahead of time like an architect or bridge designer might—and we really do want these people to plan ahead as best as possible.

In my poems or poetic process, there are no visual plans or scrolls of ideas. I just start with one letter, then [write] one word, then another, then another, then a page, then another. And mine that vein of ore, to use your metaphor. One day I look up and am usually exhausted but full of life, and then I stop. I spend months and years revising, which is maybe where the neat and organized comes into play, and I start feeling like I might have a book.

I do think, to refer back to your earlier question, that a book is just a manufactured object in a capitalistic and product-oriented culture. I don’t like when people say things like, “What do you have to show for the time you put into X, Y, or Z?” I always respond, “Nothing, and that is fine.” My obsessions and themes just keep threading along my whole life. We are who we are. The things that preoccupy us change as our lives change, such as when I had to confront my parents’ illnesses, but overall I’m still the same person I was when I wrote my first book. Maybe those threads just get thicker and wilder, just get to go in different directions.

Tell us more about Martin and how her paintings inspired the poems in this book.

I read Agnes Martin’s Writings [Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005] a while back and while I enjoyed it, I didn’t really have a visceral, bodily connection to her visual art. [Later on] MoMA in New York asked for a poem on any piece of art in their collection and I searched for a while, but it was too overwhelming. I looked up Martin’s work and suddenly, many years later, it spoke to me in a different way. I wrote a poem for the museum. When I read that poem aloud at a reading, I remember wanting to rush home to write another poem, and then I did a lot of research and kept writing in correspondence with Martin’s art. I think I had aged a bit and was also experiencing depression at that time, so something about her grids felt poignant to me.

Martin’s grids—often categorized as works of minimalism, abstract expressionism, or both—seem to have impacted your poetic forms, too. Many of the poems in With My Back to the World are prose meditations that look like tiny canvases. Often they’re mirrored with a second version of the poem, on the opposite page, that has been faded, redacted, crossed out, or drawn over, as if you’re incorporating Martin’s gestures into your writing process. Can you talk about this unique feature and how it came about?

I used to draw a lot when I was younger, through high school, but then I stopped. Lately I’ve been experimenting with various forms of visual art, whether it’s collaging or using small slips of papers to write poems on in Dear Memory. I’m not looking to make anything beautiful or skilled even—mostly I’m just wanting to use my hands to work with the materiality of perception, an experience that’s different from writing a poem.

Those visual elements in With My Back to the World were just additional ways to interact with my poems and Martin’s visual art. They were made with vellum or tracing paper and the original idea was to be able to see through the vellum to the poem that I wrote underneath it. But vellum paper is hard to work with production-wise, so they just became discrete art pieces next to the poems. I’m never particularly good at talking about why I do something, but oftentimes my obsessive nature leads me down different paths and different mediums to explore the same material.

Here’s another development I’ve tracked over time: Your poems have become far more inquisitive and, dare I say, philosophical. In Dear Memory, and certainly in this new book, questions function as a source of creative energy. Is that true for you? For instance, in With My Back to the World a poem titled “Drift of Summer, 1964” begins:

Agnes drew 44 lines vertically, 33 lines horizontally. Sometimes the ink thickens at the end of the line into a dot. I imagine her hand anticipating the ending, looking at the point and beyond at the same time. I’m afraid to follow the lines to their ends because there might be nothing after or maybe something after is more terrifying. Is it possible to feel happiness while on the line? Or is the present just the pointed tip of death’s sword?

And have these questions, even though they’re unanswerable, offered you any solace?

My brain naturally moves around a lot—perhaps too much, especially when it comes to managing my life—and the poems reflect that movement. In terms of questions and philosophy, I like to read contemporary philosophy, but not in any order or method. I just pick random books that seem interesting.

In truth, I think my parents being ill so brutally and for so long, both with very uneasy illnesses and deaths, probably influences the things I think about, which often are those bigger questions of why we’re here, what suffering is, why we have to die, etcetera. I think about questions daily. Some of the questions I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about lately are: In my time left on this planet, what do I want to spend my time doing? Who do I want to spend my precious time with? What do I want to read and look at? The answers always seem to be in the form of what I don’t want to be doing, or who I don’t want to spend time with, or what I don’t want to be concerned with, so the negative space seems to be where a lot of my answers to my questions lie, apophatic maybe. I know for sure that I don’t want to be cruel or ungenerous or petty or jealous.

On solace or antidotes, I don’t think art is an antidote to anything, but I think making art can be an antidote to a lot of things. I absolutely love reading and writing. I love looking at art and reading about art and philosophy. I love talking to people about poems, about making poems, about visual art and philosophy. That’s the solace. That’s the antidote. The outcome might not be joyful—at the risk of sounding ungrateful, I have so many anxieties about being seen or looked at that book publication can be hard—but the process of making and thinking about making is the pinnacle of joy for me. I saw what happened to my father’s brain after his stroke. Not a day goes by that I don’t appreciate the fact that I can read and write poems.

Most of the poems in this book are written in prose, perhaps because you were constructing them with Martin’s square canvases in mind. They remind me of the OBIT poems, which follow consistently narrow dimensions. How do these containers catalyze your creative thinking and feeling? Does filling these forms with sentences differ from writing lines of verse?

That’s true, I was following [the] physical forms of Martin’s artwork, and that never involved line breaks. I haven’t actually written line breaks in a while now—syllabics in The Trees Witness Everything are random. Without the line break, a poet is left without one of the [main] elements of poetry. With that kind of constraint, everything else needs to be sharpened somehow. There’s sound of course, rhythm, thinking, and more, but without the line break, how do you move a poem forward? How do you create tension? How do you create suspension, excitement, or anticipation toward the next line? Without the line break, I can really feel that sense of loss. I have been grieving for a line break, but line breaks haven’t felt quite right for the things I’ve been writing for a while. I’m sure at some point they will return, and when they do, I’ll know.

I wonder if writing in prose helped you find ways to talk about grief, especially the loss of your parents. And yet, the middle section of With My Back to the World is kind of a grief journal written in verse about your father’s death. It appears to have been written over the course of two months as your ailing father passed away, and then tracks your feelings in the wake of his death. One striking passage from that sequence is from “Feb.15.2022”:

The caskets are shaking. The white-tailed deer

gently cross the river. I hike up the

hill to find my feelings. Instead, I run

into Hope, who doesn’t look at me or

stop, but walks down the hill. Today could be

a day where everything is beautiful.

How did this long sequence emerge?

This is a hard story to relay. My father had a really bad last fall and nearly lost his entire eye. The doctors didn’t think he would recover, so we had to make some difficult choices. We thought he would pass away quickly, but he ended up, in typical fashion for him, hanging on for weeks and weeks. Those were some pretty hard weeks, and I kept a kind of poetry journal of the days of his dying. Perhaps I was inspired by On Kawara’s Today paintings. They are so crystalline and beautiful, and brutal at the same time. My poem is in syllabics, and something about counting with my fingers gave me the tiniest bit of solace that I needed at the time.

On the flip side, is it possible to read With My Back to the World as a manual of happiness? Do you feel like Martin is a spiritual guide offering instruction? Many of her painting titles point to joy: “I Love the Whole World, 2000,” “Happiness,” “Perfect Happiness,” etcetera.

It’s interesting that you mention this because her titles are fascinating. Those specific titles are from her later period, and they do feel more like emotional gesturing. From the seventies to the nineties her titles were mostly “Untitled,” which is fascinating because the viewer could bring one’s own experience into the art more. I think her body of work shows her transformation as a human and the changing of her mind and perception. I think her art is a manifestation of a growing mind.

To translate what I said as it relates to my own writing, and to be a little repetitive, I see my writing not as anything but a mapping of my changing mind and perception. That’s it. I’m a cartographer of my own brain and life experiences. For me, writing is a place where I work through my own thinking and feeling. What’s left—poems, books, art—is just what’s left of that process, what remains.

David Roderick is the director of content at the Adroit Journal and was a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing fellow for 2021-2022. He has published two books, Blue Colonial (American Poetry Review, 2006) and The Americans (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014), and lives in Berkeley, California, where he codirects Left Margin LIT, a creative writing center and workspace for writers.