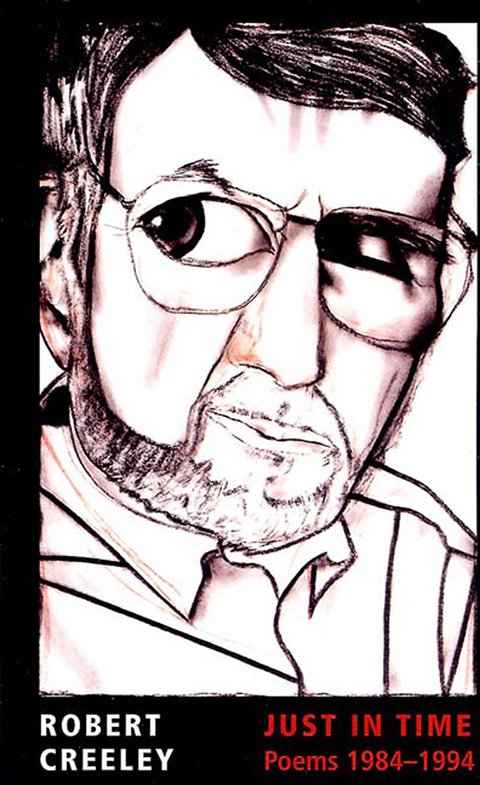

With over sixty books published during a career that spans more than half a century, Robert Creeley is one of the most prolific and influential figures in American poetry. This month New Directions is publishing Just in Time: Poems 1984–1994, which collects three of Creeley’s previous books.

I asked Creeley about the activity of collecting his early books into one volume, and how it influences the way he thinks about his past and future work.

Robert Creeley: I remember Allen Ginsberg saying of my Collected Poems, “Who would have thought such little poems would make such a big book!” I was surprised too. So there is always that new perspective, so to speak-any shift in context and format is bound to change one’s sense of things. I know that reading Williams’s Paterson as it appeared, book by book, was quite different from reading the whole work “collected” and published as a single volume.

I miss in obvious ways the intensity and specificness a particular book can have at a particular time for all concerned—Pieces [Creeley’s book of poems published by Scribner in 1969], for example. At the same time one is able to recognize in a collection such as Just in Time the pattern of a life lived, the curve of that aspect of time. For me especially “autobiographical” is a significant element, and the collection of several books into one lets one track it more simply.

Both Williams and Ginsberg were quite selective when preparing their collections. When Williams was preparing a new edition of his Earlier Collected Poems in 1951, he considered different “modes of attack” for organizing his works, and told his editor, James Laughlin, that “you would hardly know the old gal in her new dress.” Ginsberg wrote an “Apologia of Selection” for his Selected Poems, stating that the volume “summarizes what I deem most honest, most penetrant of my writing.” Just in Time collects three of your books—Memory Gardens, Windows, and Echoes—as they originally appeared. Have you ever been tempted to revise or take out certain poems when it comes time to collect them, to restore some of that “intensity and specificness”?

Choosing material for any “selected poems” has always been very difficult for me to do, either with confidence or with pleasure. I think of the poems that get left out—like waifs abandoned! I know that it took friend poet Robert Grenier to get the manuscript together for my first Selected Poems, published by Scribner in the late seventies. I just made endless false starts.

Collected poems are just that, collected—not revised, not reordered, not edited, not selected. Robert Duncan said aptly that a “collected poems” would be, presumably, all the poems extant, a collection of all that had been written and had survived. So my using the format of previous publications, both as to order and content, employs that usefully simplifying logic. For example, there’s now the University of California Press Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1945-1975. Then there are, or will shortly be, the two New Directions “collecteds”: So There, Poems 1976–1983 and Just in Time, Poems 1984–1994. (Not much more now to go!) What I have added to both the New Directions volumes are locating prefaces-cranky perhaps in their mode but particular still to the books as “collected” as well as to the person, my generic self, who wrote them.

In December, Dalkey Archive is publishing your Collected Prose. Most readers know you through your poetry, but you initially thought most of your life’s writing would be in prose. Is that right? How did your concept of narrative change as your work shifted between the genres?

I certainly began by thinking it would be prose that would occupy me. I did not at first realize I had any capability as a poet. It was finally the pleasure and ease with which poems came, so to speak, that kept me returning to them. “Poet” is a daunting thing to be in any case, just that one’s never sure of what precisely it defines. So I stayed “writer” as long as possible, and prose was a useful excuse.

Thinking of the whole concept of genre in writing, I soon realized that my prose was not that usual anymore than my poems seemed to be the expected “poem.” What was most interesting to me was the fact that the one form began to meld with the other—I even published a book (A Day Book) with the two “forms” interacting. Here Williams was, as ever, a great model and influence. By the time I got to writing Presences and Mabel: A Story, the work was effectually both prose and poem at one and the same time. So I was delighted to read Stephen Fredman’s Poet’s Prose wherein he writes of Presences so reassuringly. Narrative, be it said, is simply one thing after another. It doesn’t have to be a straight line. It’s a story, however told. What gives the most amplitude to the focus is what most interests me—which is to say, what most accommodates my thoughts and feelings in the given instance is what I am drawn to use.

Whatever accommodates the imagination. William Carlos Williams has been so important to you and your work. How did you come to know his work? When did you first encounter him?

It’s hard now to remember just when his work became so crucial for me. Certainly it was during my time in college (1943–46). I had first tried to use Wallace Stevens as a model in that I so loved his musing, ironic, playfully rhetorical address. But his pace, call it, determinedly reflexive and steady, was just not the way I was feeling or what I could use.

I remember the poems Williams sent us for the Harvard Wake—“The Mind Hesitant,” for instance. That was far closer to my sense of world and means of speaking. Then I had the early Complete Collected Poems (1938) and I had also got the record put out by the National Council of Teachers of English, a 78 that I continued to play over and over and over, even after it had a substantial crack through one side. I loved “The wind increases...” Just terrific! That was the intensity I was after.

Then the Cummington Press published The Wedge in 1944 and its preface became my credo absolutely. “When a man makes a poem...” I can still quote it almost verbatim. Then other books such as Life along the Passaic River and In the American Grain—and chapbooks such as The Pink Church, a great poem!—altogether won me over, as if there were ever any doubts, which there weren’t. Here was the model and the elder I’d been looking for and he seemed sadly as ignored then as ourselves.

I began writing to both him and Pound in the late forties, hoping for their help with a fledgling magazine that never got really started—but, most important, it gave me a chance to say how much each meant to me. They responded with amazingly generous particularity. When I was finally able to visit Williams in the mid-fifties, I recall almost keeling over when he appeared suddenly at the door. I remember him asking me if I was all right, just that I looked so pale. When I said I had never been so afraid of meeting someone in my life, he answered, “Who? Me? Come in, come in!” He was wonderful.

Kevin Larimer is the assistant editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.